Parliamentary elections held Tuesday in Israel produced a remarkable and unfamiliar result: everyone, including Benjamin Netanyahu, the longest-serving prime minister in the country’s history, lost. Neither his religious-conservative bloc nor the slightly-to-the-left party led by his primary challenger, former military chief Benny Gantz, secured enough support to form a majority. Avigdor Liberman, the head of the Yisrael Beiteinu party, a one-time Netanyahu ally and current kingmaker, could deliver a majority to the incumbent if he wanted to but appears hellbent on keeping him and his religious partners out of power.

Netanyahu has offered to negotiate with Gantz and Liberman over a potential unity government, which would feature a joint premiership like the one Shimon Peres and Yitzhak Shamir had after the 1984 election, but Gantz isn’t interested, committing again to forming a “broad and liberal unity government” on Thursday. His second in command, former prime ministerial hopeful Yair Lapid, told reporters that Gantz will form such a government as soon as Netanyahu steps aside. In short, whether or not Israel is dragged into a third election this year will depend on the unlikely event that Netanyahu abdicates power or is forced to step down as leader of the Likud party.

It’s hard to see a way out of the gridlock. Netanyahu has already signed an agreement with the religious parties Shas and United Torah Judaism and the far-right Yamina party to negotiate as a single bloc. Liberman is famously secular and has vowed to not be part of a government that also included them as members. Liberman, however, is also famously hawkish, especially toward Arab Israelis. He’s already said he will refuse to participate in any government where Arabs have a seat at the table, which all but guarantees that Gantz won’t be able to form a government either.

The results exemplify two powerful domestic forces dividing the Israeli electorate along religious and ethnic grounds. The religious-secular divide is growing in lockstep with a demographic rise in the percentage of religious Israelis, whose support kept Netanyahu in power for so many years, albeit by a razor’s edge. However, corruption allegations and indictments hanging over Netanyahu’s head, as well as higher voter turnout among Netanyahu-opposed segments of the electorate, have eaten into his majority coalition.

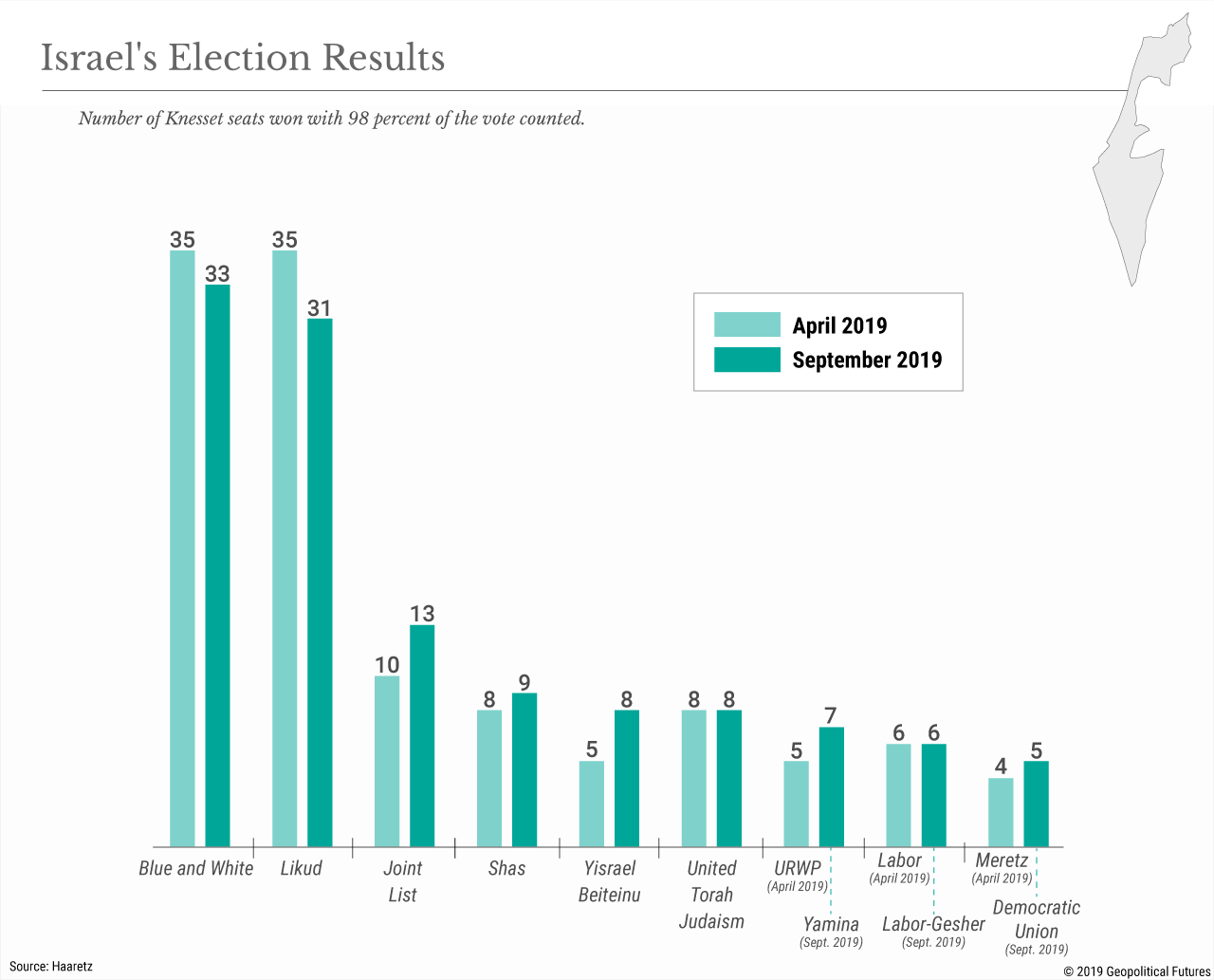

The Arab-Jewish divide is also becoming more pronounced. Three Arab parties, which represent the 20 percent or so of Arab Israelis, ran as a “Joint List” in this latest round of elections, earning 13 total seats in the Knesset (up from 10 in the previous election). This may not be that large of a number, but in such a fractured political environment, three seats can be the difference between a majority coalition and a new election. It’s unclear (but highly unlikely) that Gantz would form a government with them (or that they would participate in a government with him); no Israeli government has included them, and a new one with Liberman in tow certainly won’t either. Effectively ignoring 20 percent of the population will only make the gridlock more severe, much as it has for the past few years. On the other hand, if Gantz can assemble a unity government with Likud, and if Israeli Arab political unity holds, an Arab party could be the leader of the opposition for the first time in Israel’s history. That’s a lot of ifs, but even the remote chance of it happening underscores increased Arab political power in Israel.

Either way, at a foreign policy level, little is likely to change. If Netanyahu remains in office, literally nothing will change. If Gantz replaces him, he may prove to be different in style if not substance. In the weeks leading up to the election, Netanyahu made headlines by promising to annex “Area C,” the part of the West Bank that includes the Jordan Valley. Yet in July Gantz said the Jordan Valley “will always remain under [Israeli] control.” Some have compared Gantz to Israeli political legend Yitzhak Rabin, who also made the jump from military chief to prime minister. Joint List’s Ayman Odeh ran afoul of some of his own constituents for even considering recommending Gantz for the post, something no Arab party has done since Rabin.

Gantz may have some “Rabin” in him, in that he is a former military man coming to politics, but he is hardly the ideological heir to Rabin’s policies. The Labor Party, which Rabin led, earned just 6 Knesset seats in the election. And if he became prime minister, he would be coming into a completely different political environment, one far less conducive for Palestinian peace talks. He will have bigger security issues on his plate, namely, to keep Gaza calm, to combat Hezbollah’s growing strength in Lebanon, to limit Iranian support of Iraq and Syria, and to find balance between Turkey and Iran in general. (It may not matter in any case, since his path to premiership runs through Yisrael Beiteinu and Likud, neither of which will compromise on Palestine.)

Netanyahu’s opponents are relishing in his perceived defeat, but that’s more schadenfreude than policy coup. Gantz and Netanyahu are both generally center right, and either one will have to govern with unstable coalitions liable to crumble at the first sign of trouble. What is most significant about these election results it that they confirm what the previous election results already showed: Israeli society is divided between the religious and secular on the one hand and between Arabs and Jews on the other. The demographics of those divides are such that old political arrangements have become obsolete and that new alignments require new compromises that, at least so far, are too unpalatable to the various factions and parties to make.

Reprinted with permission from Geopolitical Futures.