China is on a charm offensive in Europe, a move facilitated by U.S. President Donald Trump’s policies and his declarations since taking office.

Beijing is eager to find allies willing to stand up for open trade amid fears Trump could undermine it with his protectionist, so-called America First measures. Sensing a low tide in Transatlantic relations, Chinese leaders are reaching out to the European Union -- China’s leading trading partner and an important source of investment and technology. Beijing seems willing to set aside differences over bilateral trade and investment in order to draw the Europeans to its side.

Trade Matters

In recent months, Beijing has toned down its public campaign to obtain EU recognition of market economy status for China. The case is now being dealt with at the World Trade Organization in Geneva, a move that allows the European Union and China to avoid giving the question too much publicity.

If China obtains its coveted prize, it will be more difficult to adopt anti-dumping measures against Chinese companies. Neither the European Union nor the United States has yet recognized China as a market economy, and Western unity on this issue has so far prevailed.

The issue of market economy status marred Sino-European relations throughout 2016 and could have tainted relations this year too, had the election of Trump not changed priorities for Brussels and Beijing. Both stand united against protectionism, and on March 10, the European Council issued a conclusion document underlining that “trade relations with China should be strengthened.”

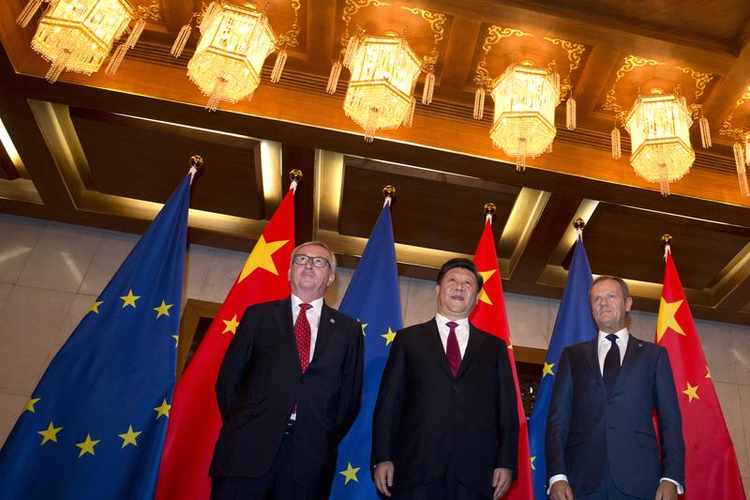

EU policymakers have accepted Beijing’s request to bump up the annual China-EU summit from its usual July date to June. This is intended to send a unified message President Trump. Brussels and Beijing want to press ahead with economic globalization and free and fair trade in order to better tackle domestic problems. China is rebalancing its economy from one based on exports to one focused on domestic consumption, while the European Union is trying to recover from a long recession. However, it is not only the economic dimension that is bringing China and the European Union closer, but also their support for multilateralism and international organizations -- in contrast with Trump’s preference for power-based bilateral relations.

Promoting Multilateralism

During the seventh China-EU Strategic Dialogue held in Beijing on April 19 and co-chaired by Yang Jiechi, Chinese State Councilor, and Federica Mogherini, the European Union’s foreign policy chief, the two sides agreed on a common vision of international affairs and global governance, advocating a peaceful international environment and cooperative relations among countries with the United Nations at the center.

China and the European Union worry that the United States will take a unilateral attitude toward global issues and depart from the multilateral approach undertaken by the administration of former President Barack Obama. They see Trump’s decision to fire a missile against the Syrian regime and to step up belligerent rhetoric against North Korea as demonstrations of a new and troubling approach.

Europe is also reconnecting with China on the question of its own future, and the European Union’s role in the world. Here again, the American president’s stance toward the old Continent is bringing Brussels and Beijing closer.

Support for European Unity

Trump’s backing of Brexit has disheartened EU policymakers. Likewise, the declarations against the euro made by the candidate for the post of U.S. ambassador to the European Union have prompted unusual reactions from the European Parliament. President Trump’s attacks on Germany, Europe’s largest economy, and his refusal to shake hands with German Chancellor Angela Merkel during their press conference at the White House, have made an unfavorable impression on European public opinion. How could it possibly be, Europeans wonder, that our closest ally is so insensitive toward us?

It should come as little surprise that under these circumstances Europe is eyeing China. Beijing has traditionally supported the process of European integration in an attempt to drive a wedge among the Western allies and lessen the dominant position of the United States. Think for instance of Chinese support for Europe’s space ambitions in 2003. That support coincided with one of the worst crises in Transatlantic relations, mainly due to disagreements over the U.S.-led war in Iraq and the foreign policy positions of the first George W. Bush administration.

When Galileo, the EU-led global navigation satellite system alternative to the American GPS, was launched, the United States firmly opposed it, fearing a challenge to its space primacy and leadership in key strategic and high-tech industrial sectors. China worked to prop up the European project, committing millions of euros and becoming Galileo’s most important non-EU partner.

Most of the EU countries involved in the Galileo project are also members of the eurozone. When the euro crisis broke out in 2009 and the European common currency became the target of speculative attacks mainly stemming from Wall Street-based banks and hedge funds, it was again to China that EU policymakers turned. Merkel and Italy’s former Prime Minister Mario Monti, among others, traveled to Beijing to seek the support of Chinese leaders who eventually intervened on various occasions to reassure the financial markets and buy eurozone bonds.

True, Beijing has primarily supported Europe for reasons pertaining to its own national interest. By keeping up the value of the currency of its primary trade destination, China has benefited from the competitiveness of its products, further augmenting the European Union’s trade deficit with China. Moreover, Chinese policymakers have not hesitated to set EU member states against each other when this was in Beijing’s interest.

Yet when support for European integration was needed, Chinese leaders have given it. Li Keqiang, the Chinese premier, stressed this point when he declared on April 19 that China “supports European integration and expects the EU to remain united, stable and prosperous.”

At a time when European unity is under threat from populist movements, it is this kind of declaration that EU policymakers expect from the United States. But with the Trump administration, this is not happening -- and that absence could have serious implications for the Transatlantic alliance. On March 25, on the 60th anniversary of the Treaty of Rome, European Commission President Jean-Claude warned of “strains in Transatlantic relations.”

Transatlantic Contrast

China stands to gain from divisions among Western allies -- even at a moment such as this, when there are a number of frictions in Sino-European relations, including the question of growing Chinese investments in the old Continent.

A report by the Rhodium Group, a research firm, and the Mercator Institute for China Studies, a think tank in Berlin, found that Chinese direct investment in the European Union surged 76 percent to around €35 billion in 2016.

Chinese purchases are growing rapidly in sectors that remain restricted to foreign investors in China, and this inflames debate about growing imbalances between the two sides. Those imbalances draw particular concern from Germany, where Chinese acquisitions soared to 11 billion euros in 2016, surpassing for the first time German mergers and acquisitions in China.

In February, France, Germany, and Italy asked the European Commission to rethink rules on foreign investment in the European Union. This was a message to Beijing to enforce reciprocity in market access, and at a time when the two sides are negotiating a bilateral investment treaty. It is unlikely, however, that a pan-European screening mechanism similar to the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States will see light in the near future. Europe is now the top destination of Chinese investments abroad, surpassing the United States. According to the China Global Investment Tracker, a joint project of the American Enterprise Institute and the Heritage Foundation, between 2005 and 2016 China invested nearly $164 billion in Europe. During that same period, it invested $103 billion in the United States.

With negotiations on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership in limbo, and the Trump administration’s focus on America First,” Europeans feel they have been left alone to deal with an increasingly powerful China. The latter is luring EU members with the prospect of increased investments in their countries.

Should President Trump not change course, the European Union and China are bound to get closer, despite their differences.