“Looking for a manufacturing guy with plant shutdown experience for an interim role in Shanghai.”

This request recently landed in my inbox. It's not exactly the stuff that age-old “One Billion Customers” dream of selling a toothbrush to every man, woman, and child in China is made of. Indeed, for U.S. companies looking to do business in China, lucrative opportunities remain elusive -- and companies more often than not jump at initial offers without looking at the long-term implications.

As their Chinese counterparts invest freely in American markets, and as Beijing looks to shift its economic model toward domestic consumption and innovation, America and China are entering a new phase in their economic relationship. It is a subtle but critical time of strategic change, and it is important that business leaders and policymakers active in China take note.

Doing Business in China Is Tough

A recent survey by the American Chamber of Commerce in China found three top concerns shared among its members: inconsistent regulatory interpretation and unclear laws, rising labor costs, and rising Chinese protectionism. This paints a picture of an uncertain and expensive environment increasingly hostile to foreign brands. Serving as backdrop are larger challenges in U.S.-China relations, from North Korea, to the Chinese yuan’s valuation, to challenges to the post-World War II order such as the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. And as U.S. boardrooms reawaken to the difficulties of finding long-term success in the China Dream, Chinese companies continue to ride the tides of trade and to cherry-pick valuable assets from the United States’ creative core.

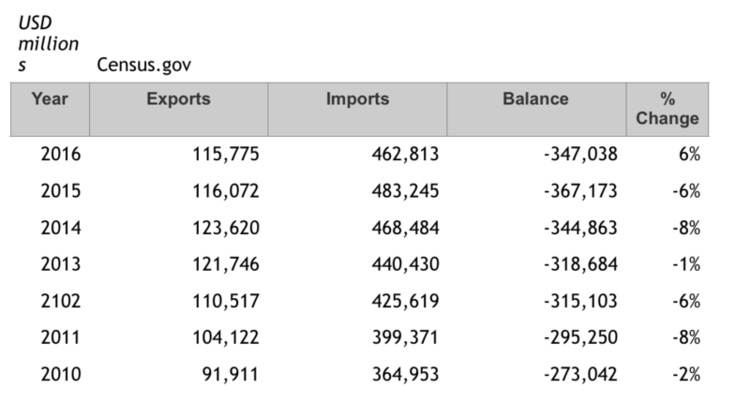

Surely there are bright spots in this picture. At the recent Mar-a-Largo summit between Presidents Xi Jinping and Donald Trump, the Chinese government offered to end a 2003 ban on U.S. beef in exchange for alleviating constraints on the sale of certain high-tech goods produced in the United States, and in 2015 U.S. lobster exports to China reached an all-time high of $108 million. However, the macro trend in trade is clearly in China’s favor. With the exception of a small surge in exports in 2013 and 2014, U.S. exports to China have actually decreased since 2014. Chinese exports to the United States, meanwhile, dropped some in 2016, but only after reaching record highs in the six previous consecutive years.

U.S. foreign direct investment in China has continued to surge forward. It hit $65.8 billion in 2014, a 9.8 percent increase from 2013, but for many the heady days of easy profits in China -- if they ever really existed -- are drying up. Two of the most touted and iconic success stories, KFC and McDonalds, have recently spun their China operations off to largely Chinese-owned concerns (KFC to Primavera Capital and Alibaba, and McDonalds to CITIC and Carlyle); Uber China was absorbed by Didi (once hailed as an Uber clone); Netflix, in contrast to the other 130 countries it opened distribution to in 2016, recently announced it would license content through Baidu’s iQiyi ( another Netflix clone); and Apple has had a slew of bruising quarters with strong competition from lower-cost local brands such as Oppo and Huawei. Perhaps most telling is that 81 percent of firms surveyed by the American Chamber of Commerce felt “less welcome” in China than before, a threefold surge from 2013.

Meanwhile, Chinese FDI in the United States tripled in 2016 to $48 billion -- an increase from $15.8 billion in 2015, itself a record -- and it doubled in Europe to $46 billion. Chinese outbound investment has been increasing at a massive scale since 2009. In that year, many Chinese firms with cash reserves began taking advantage of two events: the U.S. thirst for foreign capital after the onset of recession, and the large-scale revaluation of the renminbi between 2005-2008, which made U.S. imports cheaper in China, but also made Chinese capital more valuable in the United States. Unlike American FDI in China, this investment is predominantly driven by mergers and acquisitions, which indicates that Chinese companies are continuing to use their resources to acquire existing U.S. assets more than creating new companies. Furthermore, according to the Rhodium Group, a full 98 percent of U.S. congressional districts -- 425 out of 435 -- now host Chinese-owned companies, showing increased lobbying power in the United States.

Chinese investments are primarily strategic, and include a bid for Westinghouse, a 5 percent stake in Tesla, a $580 million acquisition of semiconductor testing firm X Cerra, and a $1 billion investment in Paramount Pictures. In April, the Federal Trade Commission approved ChemChina’s $56 billion bid to buy Switzerland’s Syngenta, pushing them to the top of global share in crop protection, and third in seeds after Monsanto and Dow-DuPont. Just a month before this ruling, the Hershey Company was ordered by Chinese authorities to stop chocolate production in Shanghai due to affiliation with South Korean joint venture partner Lotte, which bore the brunt of Chinese ire for Seoul’s acceptance of the THAAD missile defense system. Thus commerce is not safe in China from the vagaries of geopolitics.

Master Plans vs. Ad Hoc

Since 1953, Beijing’s five-year plans have provided an economic roadmap and a rallying point for the Chinese economy that can also provide some guidance to U.S. business leaders and policymakers. The 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020) codifies the China Dream idea of transforming the Chinese economy through a focus on domestic consumption and innovation rather than through the heavy infrastructure, capacity-building investment, and copy-export focus of years past. The plan would double China’s 2010 GDP and per capita income by 2020, ending overcapacity in heavy industry and dealing with debt and bad loans. Furthermore, the plan has five development and reform rallying cries: innovation for quality growth; coordination across industries; environmentally friendly growth; continued opening abroad and an active role in global governance; and expanding social services.

More details emerge in the “Made in China 2025” initiative, which focuses on expanding China’s share of the global value chain by raising Chinese-made value-added core content in Chinese exports from under 20 percent in 2011 to 40 percent by 2020 to 70 percent by 2025. The initiative also pushes private firms to have more strategic say in standard-setting and in intellectual-property protection, and an increasing amount of Chinese FDI now comes from private firms rather than state-owned enterprises. Finally, it emphasizes ten key industry areas:

1) New advanced information technology;

2) Automated machine tools and robotics;

3) Aerospace and aeronautical equipment;

4) Maritime equipment and high-tech shipping;

5) Modern rail transport equipment;

6) New-energy vehicles and equipment;

7) Power equipment;

8) Agricultural equipment;

9) New materials;

10) Biopharma and advanced medical products.

These roadmaps give a clear idea of where Beijing wants things to head, and which side of the road businesses need to be on.

In stark contrast to such a specific program, the U.S.-China economic relationship was built piece by piece with no master plan. It started with a trickle of iconic U.S. products like Coca-Cola entering Chinese consumer markets, and with the offshoring of small American factories and low-value, high-labor parts of the supply chain throughout the 1980s and 1990s. The second phase began with China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001. This spurred ever-increasing cross-border capital flows and integration, bringing us to the highly nuanced, highly competitive and high-tech duo of today’s Chimerica.

Chimerica: Entering Phase Three

Thus are we entering a third phase of Sino-U.S. economic relations, one that brings a new agenda loaded with new questions: Should China still be considered a non-market economy under the WTO? Are the assumptions of trade we made in phase two still valid for today’s China, now a superpower? Can U.S. firms and U.S. policymakers compete with the top-down, blended statist-capitalist approach that Beijing has taken with so much apparent success?

For U.S. businesses, it is important to grasp the larger geopolitical and economic strategy that Beijing is putting forth, and to ask yourself where your firm fits into this in both the short term and long term, and to not be afraid to push back a bit on making concessions and protect your prime assets in your core area of value. For Chinese industry to achieve anything like the ambitious plan laid out in the “Made in China 2025” plan will require acquiring and mastering much of the superior skill and value that U.S. and other foreign players maintain. Be cautious of quick wins, expect difficulties, and take a long-term outlook, especially when sharing intellectual property. Not having a top-down policy gives U.S. firms more freedom to maneuver than their Chinese counterparts, and remember that with its rising labor costs and unclear regulations, China is hardly the only available market. Above all, ask yourself: Will this deal look as wise in 2025 as it does today, or am I selling myself short?

U.S. policymakers must continue to ensure that gains on trade have the strategic endgame of expanding and maintaining market access. They must keep the competitiveness of U.S. firms in mind, and ensure that foreign investment policy reflects the best interests of both sides. And just as tariffs have long been an immediately effective measure in trade disputes, bodies like the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S., in addition to other broadly mandated instruments, provide vehicles to push back against non-tariff barriers to companies operating in China. Just as Beijing negotiates chocolate for missile defense, so too must U.S. firms and policymakers view investments through a strategic lens.

For businesses and policymakers, expect negotiations to be ongoing and to begin, not end, when a deal is signed. Both the United States and China see themselves as leading in and deriving much of their economic growth from new industries including biotech, robotics, driverless cars and trucks, and others which intersect the Made in China 2025 roadmap. As most of the value in these industries is in knowledge, not physical assets, the regulation and definition of how they are created, owned, protected, and exchanged will help define much of the economic success for firms and nations in the decades to come. U.S. businesses and policymakers should take pause at this critical juncture to realize that the deals they commit to and the actions they take now will help define this new phase of U.S.-China economic relations in the years to come.