Seeing the Mideast Through a Cold War Lens Will End Badly for America

While I took issue with Andrew Sullivan's idea that Vladimir Putin now "owned" the mess in Syria, Commentary's Jonathan Tobin evidently took the idea to heart and is terrified at the prospect. According to Tobin, it's quite possible that Putin could end up "owning" the Middle East with damaging results for the U.S. around the world:

The guiding principle of Russian foreign policy is twofold: annoy, humiliate, and defeat the United States every chance they get and thereby help rebuild the lost Soviet empire whose fall Putin still mourns. Russian adventurism in Syria won’t stop there. It will extend into Asia and cause havoc and diminish American influence there and everywhere else.

I think Tobin is utterly wrong in his premise that a loss of influence in one area of the world will lead to a loss everywhere (an argument that should have been put to bed after it was thoroughly discredited during the Cold War), but just for the sake of argument, let's accept that his framing is correct. Does it therefore make sense to overthrow Assad? Not even close.

First, let's look at the lay of the land. Russia has one client -- a regime that is battered by a civil war and that looks to be battling a fierce insurgency for years. It has a second, tepid ally in Iran. The U.S., on the other hand, can count on all the other major countries in the region. It's a chessboard that looks distinctly favorable to the U.S. even if Assad stays in power.

Second, for all of Tobin's breathless talk about "Brezhnev-era" diplomacy and Putin's scheme to reconstitute the Soviet empire (!), there is no chance whatsoever that Russia can re-assemble anything remotely like the Soviet Union again. It will never reclaim Central or Eastern Europe. Central Asia is independent and is as likely to tilt toward China as it is toward Russia. Ukraine, Russia's best hope for a pliable neighboring client, is also balking at Russian overtures, despite the election of Viktor Yanukovych, who was widely seen as in Putin's pocket. As Anton Barbashin and Hannah Thoburn noted recently, Russia's entire geopolitcal strategy for its near abroad is collapsing. The idea that saving Assad's bacon is an important building block in restoring Russian power makes sense only if you ignore almost every other development in Russia's Putin-era foreign policy. (It also ignores the strong evidence that Russia is in pretty bad shape domestically, too.)

Then there's the history. The last time the U.S. aided rebel groups to blunt the advance of Russian power, in Afghanistan, it ended in a transnational jihadist movement that killed thousands of Americans. Back then, the U.S. had the benefit of not knowing the danger of Islamic radicalism. Back then, Russia was a legitimate national security threat that warranted such risk taking. Today, there is no such excuse. Russia is hardly a large enough "threat" to the U.S. to warrant stoking a jihadist whirlwind in Syria just to give them a black eye.

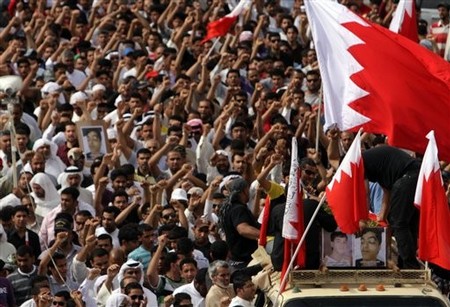

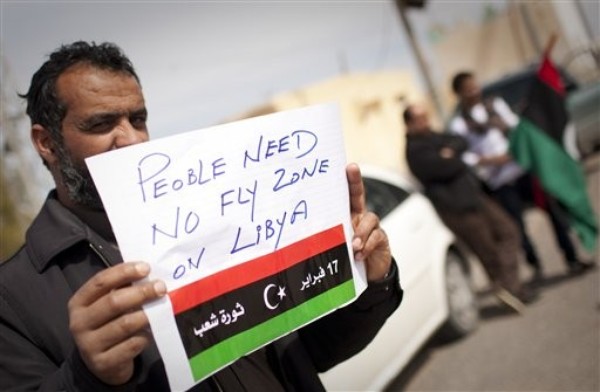

(AP Photo)