By Robert Pape

Robert A. Pape is Professor of Political Science at the University of Chicago specializing in international security affairs. He currently serves as Director of the Chicago Project on Security and Terrorism. This analysis first appeared on the CPOST blog.

Kori Schake, a valuable participant in our Capitol Hill conference on “Cutting the Fuse,” raises a number of important issues with the policy of off-shore balancing. I am delighted to respond and believe our exchange is an example of thoughtful thinking about how to move beyond the War on Terror.

Schake is right that U.S. policy makers are well-meaning; sending our ground troops overseas to advance our interests. But she overlooks how our ground forces often - and inadvertently - produce the opposite of what they intend: more anti-American terrorists than they kill. In 2000, before the occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan, there were 20 suicide attacks around the world and one (against the USS Cole) was anti-American. In the last 12 months, by comparison, 300 suicide attacks have occurred and over 270 were anti-American. We simply must face the reality - no matter how well-intentioned, our current war on terror is not serving American interests.

Schake is also right that, once we know that nearly all suicide terrorism occurs in response to military occupations by democracies, it is perfectly reasonable to ask "why some occupations and not others?" And, this has been a core element of my research, as readers will see in Chapter 1 of Cutting the Fuse and in my 2008 article in the American Political Science Review, among other publications.

In a nutshell, two factors matter.

The first is social distance between occupier and occupied, because the wider the social distance, the more the occupied community may fear losing its way of life. Although other differences may matter, research shows that occupations are especially likely to escalate to suicide terrorism when there is a difference between the predominant religion of the occupier and the predominant relation of the occupied.

Religious difference matters not because some religions are predisposed to suicide attack - indeed, there are religious differences even in purely secular suicide attack campaigns, such as the LTTE (Hindu) against the Sinhalese (Buddhists).

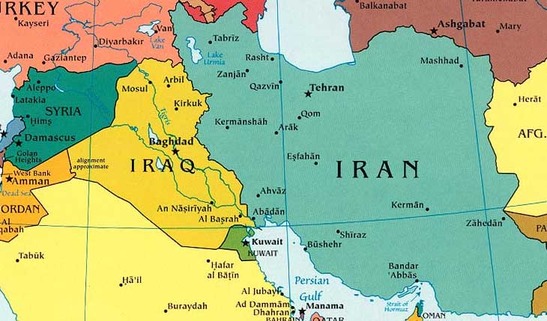

Rather, religious differences matter because it enables terrorist leaders to claim that the occupier is motivated by a religious agenda that can scare both secular and religious members of a local community – which is why bin Laden never misses an opportunity to describe U.S. occupiers as “Crusaders” – motivated by a Christian agenda to convert Muslims to Christianity, steal Muslim oil and resources, and change the local population’s way of life whether they liked it or not.

This first factor of religious difference explains why some occupations escalate to suicide terrorism, but not others – not only in recent times, but also in the past – such as why the Japanese started kamikaze attacks in October 1944 to defend their home islands from U.S. occupation, while the Germans did not.

The second factor is prior rebellion. Suicide terrorism is typically a strategy of last resort, often used by weak actors when other, non-suicide methods of resistance to occupation fail. This is why we see suicide attack campaigns so often evolve from ordinary terrorist or guerrilla campaigns, as in the cases of Israel and Palestine, the PKK in Turkey, the LTTE in Sri Lanka, etc. So, if the South Koreans ever began to resist American military presence in a serious way, this would be more worrisome than it may at first appear.

On the next issue she raises, Schake is simply wrong that “an offshore balancing approach means that we will not be engaged with military forces on the ground.” As readers will see in throughout my book, working with local allies is a core element of off-shore balancing. And, America has used the strategy of off-shore balancing to great benefit numerous times and often in concert with local allies - in the Persian Gulf in the 1970s and 1980s, in 1990 to kick Saddam out of Kuwait and in 2001 to topple the Taliban (it controlled 90 percent of Afghanistan and 50 U.S. troops, U.S. air and naval power, and U.S. economic and political support for the Northern Alliance kicked them and al-Qaeda out of the country!).

Finally, I agree that replacing mass boots with mass drones would be a mistake - since vast numbers of air strikes could inflict more than enough collateral damage to incite terrorism in response - which is exactly what Cutting the Fuse explains, and it's also why off-shore balancing means responding with stand-off military forces against significant size terrorist camps like Tarnak Farms (a military base larger than the Pentagon), and not every third ranking cadre in individual houses in Quetta, where more selective or even non-military means may well be more effective.

I hope Ms. Schake will have an opportunity to read Cutting the Fuse and to consider the research behind it. Governor Thomas Kean and Lee Hamilton - both heads of the 9/11 Commission - have, as did Thomas Schelling (Nobel laureate in Economics) and Adm. Gary Roughhead (the current Chief of Naval Operations). They too raised the issues Schake did (and more), and found convincing answers in the book.

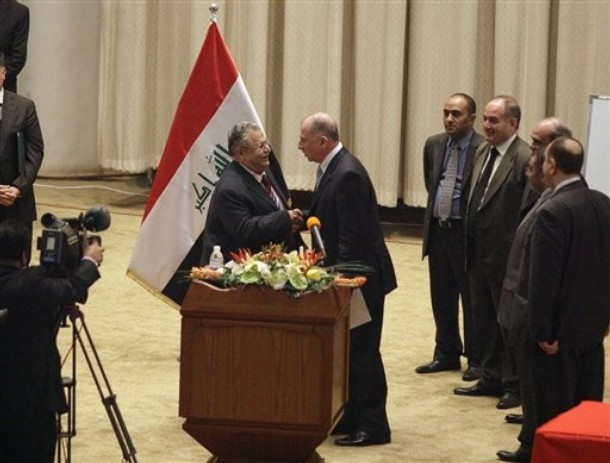

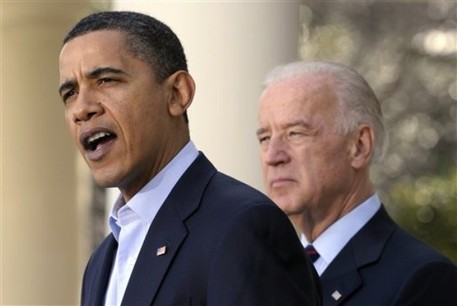

(AP Photo)