Can Ukraine Be the New Georgia?

KYIV, UKRAINE - Will what worked in Georgia work in Ukraine? It will if it is up to Davit Sakvarelidze, deputy prosecutor general of Ukraine and the chief prosecutor of the Black Sea city of Odessa. Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko has brought in veterans of the country of Georgia's reform process to help Ukraine remove the legacy of decades of Soviet and oligarchic corruption. Sakvarelidze, appointed to the national post in February 2015, and to the Odessa post several weeks ago, is attempting to bring change to the one state organization that has most resisted the political reforms sweeping the country, the General Prosecutor's Office, which enjoys very low trust among the Ukrainian people - indeed, for good reason. I sat with Sakvarelidze last week, during a visit to the Academy of Prosecutors in Kyiv, to discuss the challenges ahead of him. The place was teeming with young, energetic applicants making their way through the new selection process. There seemed to be a pervasive, youthful motivation, albeit possibly naive, with the people I met while engaged at the facility.

Sakvarelidze was the prosecutor in Georgia's capital, Tbilisi, in 2009-2010, and deputy prosecutor general of Georgia from 2010 to 2012. Along with former Georgian Prime Minister Mikhail Saakashvili and others, Sakvarelidze is working to bring trust in government to the Ukrainian people. He actively coordinates with Saakashvili, who is now governor of Odessa, through his position as head prosecutor. The governor is also working to revitalize this strategic port in a historically corrupt region of Ukraine.

Sakvarelidze is attempting to overhaul the General Prosecutor's Office and remold it into a professional force that can deal with the sickness destroying Ukrainian society. The number of prosecutorial positions have been reduced significantly and all candidates, even current hires, must undergo rigorous testing and training to be accepted into the new reality. More than 700 positions must be filled.

Sakvarelidze: "Many people will lose their jobs. They are supported by politicians and business interests, oligarchs, etc. The strongest challenge will be in the actual interviews and selections at the end of the process. It is a public relations battle. We have people trying to discredit us already. That is why we have made the process as transparent as possible. We have also increased salaries so the temptation to take a bribe will not be there. They can survive on this salary ... We will reconstitute it from the ground up, starting with local offices and then to the regional and national level."

The entire effort is behind schedule. In fact, the newly created National Anti-Corruption Bureau cannot begin its work until the prosecutor's office is up and running. Yet Sakvarelidze is optimistic and seems determined. "Ukrainians have very good organizational skills," he says. "They are very European. If given the chance, they can succeed. We have to show the new Ukraine is going to be different.

"I'm not afraid to say that an internal ‘Maidan' [referring to Ukraine's revolution] is going on in the Prosecutor General's Office which we have never seen before. Political changes have reshaped the political structure, but the Prosecutor General's Office has not changed; the system has remained the same. Now we are trying to correct it," he recently said at the 12th Yalta European Strategy Annual Meeting in Kyiv.

Regulatory reform should also be a big part of the anti-corruption effort, according to Sakvarelidze; the ability for bureaucrats to siphon cash from the public needs to be reduced. In Georgia, the time needed to get a new passport was reduced to 60 minutes. The new police force patrolling the streets of Kyiv is also a big part of the new Ukraine. The force is there to protect and to serve, not to use the average citizen as a piggy bank to better your lifestyle and pad your pension. They have even adopted Western-style uniforms to reinforce this point.

The stakes for Ukraine are huge. There have been many half-baked anti-corruption campaigns in the past that lacked the political will for real reform. This time Sakvarelidze hopes it's different. "It is not just Ukraine who will feel the pain if we fail. Ukraine is the gateway to Europe, a wall against the tide of Soviet-style corruption. I'd hate to think of the consequences to Europe and the world if we fail."

(AP photo)

Poroshenko Pokes the Bear Ahead of UN Summit

On September 26, Ukrainian TV stations broadcasted an interview with Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko, who spoke briefly about the main aspects of domestic and foreign policy of his country, and answered a few questions prior to his departure for New York City for the UN General Assembly meetings this week.

Regarding his work at the United Nations, Poroshenko mentioned that a global coalition in support of Ukraine has already formed, though it must be strengthened further. The Ukrainian president, who just turned 50, also spoke of the need to change the principle of the UN Security Council concerning the right to "veto" UN actions, as well as of the election of his country to the status of non-permanent member of the Security Council. Poroshenko confirmed that his country will use all available means to put international pressure on Moscow.

On the preparation of upcoming elections in the restive Donbass region and sanctions against Russia, Poroshenko said that Minsk agreements that were signed by Russian President Vladimir Putin clearly stated that the electoral process (in the breakaway region) should take place according to the Ukrainian legislation and laws, and if the Russian Federation supports separatists' initiatives, then it will face international sanctions. "Putin put his signature down on the document in Minsk. Thus, Russia has committed itself to the withdrawal of foreign troops from the territory of Ukraine, closing the border between our countries, ensuring the return of Ukrainian sovereignty over the territories occupied by the separatists and ensuring effective political processes in eastern Ukraine in the form of free will of its citizens during the elections, which should correspond to the OSCE standards and will be recognized by international observers," stressed the head of state.

On Putin's efforts to restore Russia's power on the global arena, Poroshenko said that by creating tension and fanning conflict situations around the world, the Russian president is trying to return his country to leadership of international politics "through the back door": "The presence of Russian troops in Syria, the presence of these 'green men' is very reminiscent of the beginning of the Crimean annexation and aggression in eastern Ukraine. What did it lead to? That is what Putin needed -- destabilization in different parts of the world, but Ukraine was his top priority. All by now know the value of such attempts, all clearly understand the role of Russia as a powerful destabilizing factor," said Poroshenko.

(AP Photo)

The Geopolitics of Respect: The U.S., China, Russia, and Iran

When the Chinese Communist Party took power in 1949, Mao Zedong declared to a party conference that "the Chinese people, comprising one quarter of humanity, have now stood up. The Chinese have always been a great, courageous and industrious nation; it is only in modern times that they have fallen behind. That was due entirely to oppression and exploitation by foreign imperialism..." Mao's regime thereafter turned China into a totalitarian society for decades, but the nationalist mantra - that China had "stood up" - became an enduring aspect of the Communist party legitimacy.

Subsequent Communist revolutions made the same claim to be at once Communist and nationalist. (Not understanding this undermined American efforts in the Vietnam War.) Anti-colonialist national independence movements of the 1950s-1970s that were not Communist did likewise - these included the Castro overthrow of Batista ( a struggle that was not originally Communist); the Algerian National Liberation Front's defeat of France; and various African revolutions against British, French and Portuguese colonial powers. Even allies - France's Charles de Gaulle was one - may resent the power of the very country that protects it. De Gaulle's obsession with national independence was not anti-American, it was pro-French and pro-European. Any people that has the means to defend itself and does not make the effort shows a lack of self-respect. Even resistance that ends in defeat can demonstrate self-respect. "Nobody wants a foreign master," said the ancient Melians to the Athenians before being crushed by them. Alexis Tsipras was just re-elected because Greeks felt he fought the good fight before accepting what he could not prevent. "(In) Europe today," his victory speech asserted, "Greece and the Greek people are synonymous with resistance and dignity."

THE WORLD'S LEADERS COME TO NEW YORK

As world leaders gather for the annual opening of the U.N. General Assembly, a geopolitics of respect is a hidden agenda. The self-confidence of strong geopolitical power is always on display (as is the bravado of certain weaker powers). But respect for cultures, histories, and past grievances concerns even the great powers. The United States, the world's only superpower, is almost always the target of recriminations. Demands for respect by the United States are the core aspect of what might be called the world geopolitics of emotion, which is no less real than military capabilities. Resentment of greater powers, and historical memories of defeat and outside interference, often produce a desire for revenge. The opposite of feeling respected is feeling humiliated, and that sense can drive irrationality in international policy.

Three countries among the biggest powers - China, Russia, and Iran - arrive at the United Nations carrying the issue of respect as a hidden agenda behind the conflicts of interests and policy. To different degrees, all three are oppressive regimes, each in its own way with its particular ideological justification, whether those be the Chinese Communist Party's alleged superior wisdom and management skills, Russia's legitimate sphere of interests as a Great Power, or Islam's right to a national theocracy. Significantly, each considers itself a civilization as well as a country. China vaunts a 5,000-year history. Iranians are the avatar of ancient Persia, whose empire began with Cyrus the Great's conquest of the Medes in the 6th century B.C. Russia's governments from Peter the Great to Vladimir Putin represent a 1,000-year power that began in 9th century Kievan Rus. If Beijing, Moscow, and Tehran are America's principal geopolitical rivals, their sense of the dignity of their own histories and cultures creates a natural resentment of American claims to a unique place in world politics and political culture.

Putin's Russia

Vladimir Putin is cited repeatedly for saying that the collapse of the Soviet Union was the greatest political catastrophe of the 20th century. What he meant was not that Russia should return to Soviet politics and economics. He was lamenting the collapse of a powerful Russian state as such - of Russia as a great power. During the Cold War the U.S.S.R. was the second superpower, the only country in the world that, because of its nuclear arsenal and international Communist empire, dealt with America as an equal. Putin wants a Russia that counts, whose voice in international relations must be reckoned with in major international issues. Russia's history implies a geopolitical calling in which the Soviet Union, because of weak leadership, is an unlamented failure. Russia's post-Communist governments, Mikhail Gorbachev's as well as Boris Yeltsin's, were humiliated by the West. Gorbachev lost the Soviet state and the international Communist movement, obliged to accept the eastern expansion of NATO and the European Union. Yeltsin oversaw Russia's economic collapse and NATO's expansion to Russia's own borders.

Putin's aim to reverse Russian geopolitical decline is self-evident. Taking Crimea, intervening in Ukraine's eastern territory, and now allying with Iran in Syria, constitute geopolitical gains in themselves. That they have occurred despite American and Western opposition is an additional source of satisfaction, both emotional, and, in the realism of global chessboard strategy, intellectual. Putin clearly enjoys playing the game. He is showing that Russia may be only a regional power, but in that region it can intervene abroad with success if not with impunity. Russia has new openings for alliances if not friendships. Putin arrives at the United Nations with more impact and reason for self-satisfaction that had seemed likely a short time ago. This includes a scheduled private meeting with Pope Francis.

Iran

Negotiating its nuclear program with the P5 + 1 big powers over the past few years put Iran at the center of the broad evolution of Middle Eastern geopolitics. Islamist jihad movements - Islamic State but also the remnants of al-Qaeda and smaller networks - may have had their day, especially as Russia and Iran commit to combat them with ground forces. What Tehran intends in the region is a matter of great importance.

According to media reports, the region's Sunni Muslim governments - Saudi Arabia, the Gulf States, perhaps Turkey as well - are not as concerned about a possible Iranian nuclear weapons program, which the nuclear agreement delays for many years, as with the expansion of Iran's regional influence. In spite of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's criticism of the nuclear agreement, this may be Israel's major concern as well. Tehran, he says, controls five Middle Eastern capitals. But a nuclear arms race in the Middle East is less likely than it once seemed to be.

Iran's increasing geopolitical influence is unquestionable. What Tehran wants from the world's powers, especially the United States, is some guarantee that regime change is not Western policy; and it wants some accommodation of increased Iranian influence, which, as is the case with Russia, is justified by Iran's size and geopolitical importance.

Also as in the case of Russia, there is the issue of respect of Iran as the inheritor of a civilization and as a religious achievement. The nuclear negotiations had a symbolic quality as well as strategic significance. The government of President Hassan Rouhani and the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei can assert that Iran stood up to the world's biggest powers, six to one, as an equal. Iranians may or may not be convinced. Another reading is that Iran's negotiating team looked more like a misbehaved schoolboy facing a disciplinary committee.

The fact is that Iran was not publicly humiliated, whether because it was supremely crafty or because the P5 + 1 took great care, which is not surprising since Russia and China were involved. Its statements of intent were not accepted at face value; neither were they rejected. Everyone, including Tehran, understood that the agreement's success or failure lies in verification of Iran's compliance. Even the concern that Tehran might cheat is a paradoxical statement of Iran's autonomy in the sense that Tehran cannot be completely controlled from outside.

Khamenei and Rouhani, whatever their differences, share a preoccupation with self-respect and with international respect. Khamenei emphasizes that Tehran will "verify Western compliance" as well. Rouhani and foreign minister Mohamed Javid Zarif sometimes take a less hostile line, along with warnings and criticism about American and Israeli actions. Iran, Rouhani says, won't forget past U.S. interventions. But the main thing, he says, is to look ahead rather than let policy be decided by the past. Respect from the United States may weigh in internal debates in Iran's leadership.

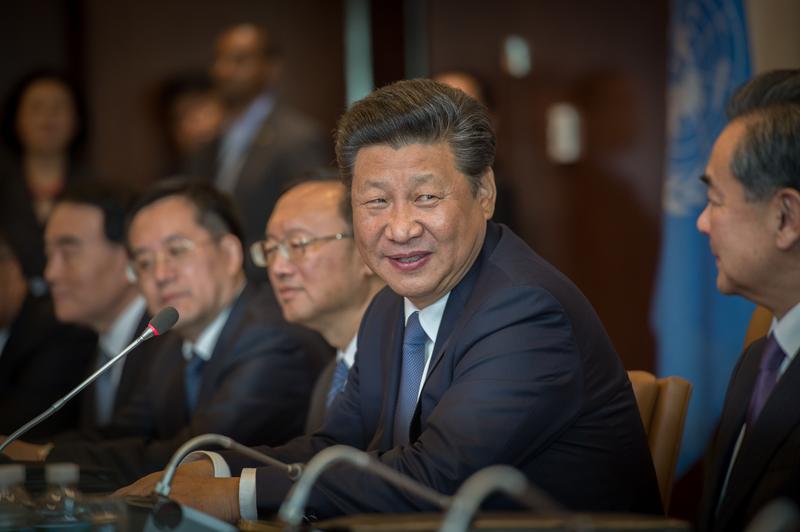

China

Chinese President Xi Jinping arrived last week in the United States for a state visit and the ritual speech at the U.N. General Assembly. He landed first in Seattle, where he made an important speech detailing China's self-definition and its subdued economic ambitions at home ("a modestly prosperous society" by 2020; a fully prosperous society by 2050. The goal of a "Communist society" is, in other words, a dead letter.) Most important was what he said about Sino-American relations. The key phrases were "to construct a new major power relationship," to "read each other's strategic intentions correctly," and that, whatever conflicts of interest or perception, "the most important thing is to respect each other." Xi appeared self-confident himself, even garrulous, reciting a list of Western books he's read, including, his favorite, Ernest Hemingway's "The Old Man and the Sea".

President Xi represents a country whose business, economic and financial interests are more than ever engaged in the international order. China's evolved world outlook is an example of how durable success blunts the impulse to invoke past grievances - the "century of Chinese humiliation" - in a country's diplomacy. Russia and Iran are far from having reached this point. Downplaying the effects of current economic difficulties and stock market volatility, Xi could have, but did not, compare them to the 2007-12 U.S. and Western financial crisis.

China is the least urgent of Washington's three major geopolitical worries. But in the long term it is America's most substantial global partner and competitor. It is uncertain how far Beijing will take its efforts to become a global power, or to what extent it will keep its promise not to try to overthrow the international order, but to revise it in favor of developing countries. What is certain is that Beijing knows it will be impossible to supplant the United States as the world's pre-eminent power and that in strategic terms it would be a waste of resources to try.

Xi's more open, self-confident attitude toward the West can affect Chinese political culture even in the Communist Party, not least of all through his cosmopolitan interest in other countries' cultures. China's opening to the world is still a work in progress, but the old Communist hostility to the West is giving way to curiosity and respect. The large number of successful mainland Chinese in the United States reinforces this trend. It gives Beijing another important stake in its relationship with America

America and the geopolitics of respect

President Obama will speak at the United Nations with the question of respect also at issue. Big power attitudes toward U.S. foreign policy are unique, however, because it is the world's sole superpower. It has the largest economy, the strongest military and the strongest power of attraction as a society. For other governments, the United States is the country whose respect is most important, and the lack of it most resented. The Obama administration has from the beginning had to deal with foreign perceptions of condescending American attitudes, and the idea that America imposes its values on other countries. Obama intuited the importance of respect. From the beginning of his administration he emphasized that he was attuned to it.

A combination of resentment, fear, and perhaps hatred, but also respect, alliance and friendship, is the natural condition of great geopolitical power. The United States is no exception. What is in question is not respect for America as such or the attractiveness of American society, but the depth of Washington's foreign policy engagement in world troubles, and the credibility of its commitments. The Obama administration, inheriting two wars, wound down military engagement in the war of necessity in Afghanistan and above all in the war of choice in Iraq. America today is fighting no ground wars. Obama is criticized for pulling American forces out of Iraq precipitously and for insufficient engagement in the Syrian wars, including the fight against ISIS/Islamic State. In any case, as opposed to the situation only a few months ago, Islamic State is now little heard from. Whether it's headed for destruction has become a reasonable question.

Russian intervention into Syrian territory, and its burgeoning alliance there with Iran, worry Washington and its allies in the region. Yet with U.S. participation, the result could be stabilization in Syria and a guarantee of Iraq's integrity. This reduces America's influence in the Middle East, but Obama's calculation is that overall reduction of U.S. attempts to control how the region evolves will benefit America's interests so long the United States protects its allies and underwrites their common interest in pushing back against Iran and Russia. Obama's calculation in the Ukraine conflict has the same intent.

The issue is whether Obama has, despite certain failures and mistakes, balanced American national interests, capacities and commitments to our most important allies. American foreign policy should not have a single rule guiding all interventions abroad. Individual cases should be evaluated, and the ambition to be the decisive force everywhere in the world should be modulated. It makes no sense to attempt to control every situation when new rising powers make it futile. Respecting the geopolitical power of others is simple prudence. At the least, Obama's awareness of the geopolitical importance of respect, rightly given, shows that American diplomacy is capable of a more cosmopolitan mentality than it has carried in the recent past.

(AP photo)

Syria May Be Putin's Afghanistan

The United States and other Western powers have voiced concern over Russian President Vladimir Putin's decision to send combat fighters, sophisticated weaponry, and eventually troops to Syria. That concern is legitimate. Russia's authorities haven't hidden their readiness to come to the rescue of a brutal ally - Bashar Assad - who has not hesitated to drop barrel bombs and use chemical weapons against his country's civilian population.

Yet no one should be more concerned with Putin's move than Putin himself. For Russia's escalating involvement in the Syrian battlefield may quickly turn out to be a geopolitical millstone for the Kremlin.

For sure, Putin's involvement in Syria is likely to be less strenuous and resource-consuming than the Soviet entanglement in Afghanistan in the 1980s. All the same, the problems that Russia's expanding presence in Syria will likely create for Putin's regime are reminiscent of those that brought about the Soviet rout in Afghanistan.

For starters, Russia will be utilizing resources on two fronts, Ukraine and Syria, at a time when the oil-market slump, Western sanctions, and the inefficiencies inherent to Russian crony capitalism are putting a severe strain on that country's economic and financial capabilities and, consequently, on the viability of Putin's strongarm moves.

Putin's Syria gambit is all the more risky as the anti-Assad governments of the Middle East, in particular those of the Gulf States, will not spare the efforts and the financial means to offset Russia's increased military assistance to the Syrian government. Some of them will not mind doubling down on their support to their proxies operating in Syria, placing these in a stronger position to fight not only Assad's crumbling army, but also the newly arrived Russian troops.

It can be expected that the anti-Assad terrorist groups already engaged in the Syrian theater of operation (the Islamic State group and al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al Nusrah in particular) will, in turn, have to slow the pace of the atrocities they commit against Syria's citizens - if only to recapture the sympathy of the population - so as to concentrate on a more pressing, life-or-death endeavor, namely to face and combat well-equipped Russian troops posted in Syria.

The behavior of Iran-funded Hezbollah sheds light on this dynamic. Hezbollah has had to reduce and put off its attacks against its main target, Israel, in order to defend the battered Syrian regime. ISIS and Jabhat al Nusrah will probably reprioritize in full to cope with Russia's military might.

For their part, the Gulf States as well as Turkey will be more dependent on U.S. logistical assistance. They will thus show more willingness than in the past to take into account and meet the conditions set by Washington in exchange for such assistance.

The United States stands to gain from all these developments. Washington, therefore, has no interest in offering Putin an easy way out, for instance by accepting a trade-off involving Russia's agreement to the departure of Bashar Assad in return for the installation of a regime in Syria with new faces but still controlled in part or in full by Russia and Iran.

No less important, now that the Syrian regime is in tatters, the the region's Sunni, anti-Assad governments will hardly be satisfied with a merely cosmetic change in Syria's top echelons of power. They may aim at a more meaningful victory; namely, a substantial reduction of Iran's control over Syria - a condition that Russia doesn't seem ready or able to agree to.

Furthermore, not even on humanitarian grounds is peace at any price a desirable objective. As cautioned by political scientist and military strategist Edward Luttwak, a victory by any of the major contenders - be it the Syrian regime with new faces or an insurgency infiltrated and dominated by militants - would trigger a slaughter against the losing communities and factions even more horrific than those seen thus far.

No solution seems more viable and durable than the status quo or a variant thereof. A national unity government, encompassing figures from both the present regime and moderate factions of the insurgency, would be too disparate, weak, and exposed to terrorist groups to last or to effectively rule.

Like it or not, the Syrian standoff is there to stay. The rivalries are too deeply entrenched, and the combat means at the disposal of belligerent factions are too exorbitant, for peace and stability to be an attainable objective in the months or years ahead.

Under such circumstances, Washington and its allies have no better option than to work within the Syrian conflict - to avoid making empty promises or setting vacuous red lines, and to avoid vain attempts to fix it.

Seen from this perspective, it's better to allow, and even to push, Vladimir Putin to become entangled in the Syrian quagmire - Ronald Reagan allowed the Soviet Union to do just that in Afghanistan.

(AP photo)

The Return of Political Economy

The second decade of the 21st century has been marked by the return of political economy, as realpolitik has replaced the globalization theme in the framework of geopolitics. Considering the key events in 2014 - the Ukraine crisis being the most prominent, but also the fall in the price of oil and the struggles of the eurozone - relative standing in the global economy is now one of the most important factors in the relations between major geopolitical actors.

Military alliances are reinforced by economic linkages among the allied countries. Regional integration efforts take into account market opportunities and risks as well as security challenges. Two agreements currently under negotiation - the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership - have the potential to create a new level of coordination between the United States and its partners. The accords would not only impact trade, but also aim at regional regulatory harmonization. The two partnership blocs, covering the Atlantic and the Pacific, would add political ingredients to economic interdependencies, positively influencing security coordination among partner states.

The return of political economy for global interdependencies

In the post-Cold War period, globalization was defined through diminishing trade and investment barriers. This created growing interdependencies among nation states, suggesting that liberalized markets and open democracies were the recipe for prosperity. Statistical data observed in both trade and investment stands as proof of how markedly global integration developed from the early 1990s until 2008. Eastward expansion of NATO and the European Union, coupled with the secure dominance of the world's oceans by U.S. naval forces, seemed to create the framework for a world dominated by Western values. It was a framework for complete peace - a peace guaranteed and supported by the integration of the global economy.

The processes that developed in the 1990s convinced everyone that global integration was not only achievable, but would also provide the needed support for global sustainable development. In that spirit, in 2001 the World Trade Organization launched the Doha Round of talks. Members convened in Qatar, hoping to spur developed and developing countries to compromise on conflicting trade policies. It was high time for true globalization, and the participating countries hoped to free up markets in agriculture, manufacturing, and services. The deadline of January 2005, set in Qatar, was never reached, while signs of failure began to show as early as 2003, when participants started missing deadlines on deals, and a September WTO meeting in Cancun, Mexico, collapsed.

The financial crisis of 2007-2008 further illustrated the vulnerabilities created by interdependencies. Finally, as the Ukraine crisis unfolded, 2014 affirmed the dominance of the political in "political economy" - a return to the realpolitik game of power. With the West having enough problems of its own, it took awhile for Europe to enforce sanctions. Once they are installed, it was a political decision, one that marked a return to hard economic competition at the global level. There's also the speculation around the oil price drop and the so-called currency wars, but it was the sanctions that essentially showed that everything is political after all. The dream of a closely integrated world driven by market forces - the main ideological trend of the 1990s - has shown its limitations, as recent events revealed that the nation-state remains a key player in international affairs.

In the second decade of the 21st century, we entered into the post-post Cold War period, and the nation state is reaffirming itself as the core actor in the global system. Adam Smith and David Ricardo are required reading once again, with the insights they provide on the links between politics and economics - and ultimately, societal well-being. While the "invisible hand" seemed to work best during the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s, showing that efficient markets can be the outcome of individual decision-making processes, what became evident from the financial crisis of 2007 is that those choices were framed by the political systems in which they were made, just as the political systems were shaped by economic realities. This is a recurring theme of Smith's "Wealth of Nations." In similar fashion, Ricardo's competitive advantage theory appears to stand at the core of international negotiations both within and outside the alliance framework. Taking into account the three power pillars for nation-states - politics, economics and military - classical economists teach us a great deal about the relationship between political and economic life, improving our understanding of the security fundamentals that set the basis for military strategies.

2005-2008: A Pivotal Triennial

Multilateral negotiations on global trade and investment regulation have been put to a halt since 2008, when the Doha round talks in Geneva ended with no result. Instead, regional integration initiatives have picked up. After consultations that began in 2005, the United States and the European Union in April 2007 signed the Framework for Advancing Transatlantic and Economic Integration, the document which led to the first version of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, or TTIP, in 2011. In November 2009, U.S. President Barack Obama announced Washington's intention to join negotiations for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, or TPP, an initiative launched in July 2005 as an expansion of the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership Agreement by Brunei, Chile, Singapore, and New Zealand. Ironically, both TTIP and TPP are ideas from the year 2005, the presumed and failed deadline for the Doha Round. Negotiations for regional integration have slowly replaced those for global integration, leaving some of the ideals of globalization behind.

In 2008, the financial crisis crossed the Atlantic, first into Europe and then on to Asia. While the crisis was felt more strongly in Europe in 2009-2010, it was in 2008 that it evolved from a national crisis to a global one. It was the aftermath of the financial crisis that installed political economy as the new realpolitik. At its core, the financial crisis was in fact a legitimacy crisis, bringing the financial and the political elites under question for their roles in the capital market. The current evolution of the crisis on the Eurasian continent is shaping geopolitical dynamics. The origins of the financial crisis stand in the risks created by interdependencies. The financial markets being interdependent, the crisis spread very fast - until 2008, no one thought interdependency and global markets could be something bad, because globalization was basically taken as a positive phenomena. However, globalization, especially in the financial markets, meant low or no regulation, and therefore no protection for local and national economies.

The origin of the financial crisis - the subprime meltdown in the United States - has appeared as a consequence of the financial system generating paper assets whose value was dependent on the housing prices, assuming that the prices would either always rise - or whose value, even if fluctuating, could still be calculated.

Instead, when the price of housing declined, the paper asset became indeterminate. The financial crisis broke out in the United States, and, because EU financial institutions also bought the paper assets, it spilled over the Atlantic. The financial elite was perceived at the time as violating principles of social and moral responsibility in its pursuit of profit. At the same time, the political establishment was seen as incapable of setting up the needed regulations to prevent the financial elite from manipulating the financial system to its own benefit in an uncontrollable manner. Thus in the aftermath of the crisis, the legitimacy of the financial and political elite is under scrutiny.

In addition, the management of the crisis, involving government intervention and bailouts, with direct consequences both on sovereign debt levels and on state power, has prompted new considerations on the link between politics and economics. For Europe, the political crisis was also deepened by the disproportionate economic problems within the European Union. Europe did not act as a single unit to deal with European banks, working instead at the national levels and through the European Central Bank. As the crisis deepened and the recession generated more problems for peripheral countries such as Greece, two narratives evolved. One is the German version, holding that Greece fell into a sovereign debt crisis because its government maintained social welfare programs far exceeding its scope for funding, and now the Greeks were expecting the European Union to bail them out. The narrative shared by Greece and other peripheral European states is that, through Europe's free trade zone, Germany created captive markets for its goods, while the importing countries, members of the same monetary club, couldn't devalue their currencies. Furthermore, it seemed that the European Central Bank favored Northern Europe in general, and Germany in particular, during the first stage of the financial crisis on the Continent, considering its focus on keeping inflation low.

The debate over solutions for the eurozone crisis has underlined the different political approaches of the member states. As discussions have devolved into a blame game between southern and northern countries, the risk of fragmentation of the European Union has further increased.

Recession in the United States and Europe affected Asian economies, particularly China and Japan. Considering the export market dependency of those countries on both Europe and the United States, the Chinese government faced a possible unemployment crisis, as low exports could have slowed production, an eventuality followed by layoffs and factory bankruptcies. This could have led to massive social instability in the country.

Beijing averted the crisis through two main policy lines. The first was to keep production steady by encouraging price reductions, and the second was to extend unprecedented credit lines to enterprises facing default on their debts in order to keep them in business. The side effect of such policies was inflation, to which China responded (again) by increasing wages. This, in turn, again increased the cost of goods exported, making China's wage rates less competitive. The global financial crisis has forced Beijing to seek out and speed up structural reforms, putting household private consumption at the core of the new economic model China seeks to implement. All this has in fact increased the government's political control over the economy.

Japan, already facing economic problems at the end of 2007, has had to deal with both the effects of a strengthened yen, which already made its exports expensive, and with the global slowdown. Ultimately, Japan's response was the three-part plan called Abenomics promoted by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. The plan aims to revive Japan's economy through structural reforms that also serve to frame a new economic model for the country. Part of the plan is making use of the Trans-Pacific Partnership to launch strong domestic reforms.

For Russia, 2008 was the year of war with Georgia - an event Moscow used to make its resurgence visible at the global level. Moscow's goal was to show former Soviet states seeking alliances with the European Union and NATO that the West could not back up its security commitments.

The root of the Georgian conflict is found in the West: the expansion of the European Union and NATO into Eastern and Central Europe was undermining Moscow's influence, and the Kremlin decided it had to do something about it. The West's recognition of Kosovo's independence from Serbia - a traditional ally of Russia - in early 2008 set the process of war in motion. Between 2000 and 2007 Putin's priority was to "clean house." The Kremlin recentralized the country politically under a pro-Putin political party, and socially by rallying nationalism. Economically, the Kremlin recentralized the majority of business and financial drivers in the country by creating state champions for energy, banking, and other sectors. As the Kremlin's control over Russia intensified, Moscow turned its attention to its periphery and to the growing pro-Western movement on the edge of the Russian sphere of influence. The pro-Western revolutions in Georgia in 2003 and in Ukraine in 2004 served as a wake-up call for Moscow. In the early 2000s, Russia used energy as the primary tool to influence Europe and penetrated European business circles. It also sought to understand and use to its advantage the European Union's socio-political problems, and the incomplete integration of the Union. The Europeans have since followed through with some of their plans for energy diversification, and Russia is facing increased economic problems, also as a result of the sanctions imposed by the West; Moscow's tools for influencing the EU have thus also weakened.

Interdependencies mean, under these circumstances, that countries can use economic policies as foreign policy and security tools. Political economy has been used at the global level to rebalance power among the resurging world's regional leaders. Aversion to the risks involved in establishing global interdependencies leads to regional capital constraints, both on trade and investment. At the same time, increased regional integration through the establishment of smaller clubs for trade and investment leads to the existence of competing trade and investment regimes. Still, such clubs facilitate more effective coordination among member states; they create trade rules that serve the states' interests and increase their outward relative power.

The meaning of partnerships

The Trans-Pacific Partnership, as well as its so-called companion, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, are adding a new dimension to regional integration. They aim to create a common market among the participants, not just a free trade zone. The proposed partnership would establish a unified set of regulations that not only address the tariff and non-tariff trade barriers but also formulate the investment rules, creating solid, long-term links among countries. This way, the established partnerships are looking to balance political relations among countries in order to alleviate any future geopolitical and security dilemmas.

For Asia, post-Cold War globalization meant an increase in regional trade interdependency, particularly with China, while maintaining a constant pace of trade links with the European Union and the United States. While dependencies on China increased, those on the European Union and the United States decreased. ASEAN - the Association of South East Asian Nations - has been one of the catalysts for growing regional cooperation. Integration, however, did not follow. To answer the need for more coordination and market access, the Trans-Pacific Partnership was conceived in 2006 by Singapore, New Zealand, Chile, and Brunei, out of the foreseeable failure of the WTO Doha round. The United States became officially involved in 2009, after the Doha round collapsed.

The TPP is designed to increase trade in Asia but it is also a response to growing Chinese economic ties in one of the most economically vibrant regions of the world. While speculation that China may join negotiations has bounced around in the media, Obama clarified the relationship between the TPP and China in an interview with the Wall Street Journal in April 2015. He said that if the "U.S. doesn't enact a free-trade deal with Asia, then China will write the rules in that region". The United States wants to create a framework across the Pacific that will become the reference point for any future big regional trade liberalization initiatives.

In this sense, the TPP truly became a grouping of global relevance in 2013, when Japan joined negotiations. Tokyo's decision followed Sino-Japanese diplomatic tensions over the disputed Diaoyu/Senkaku island chain in 2012, and it came after Japan lost the title of world's second largest economy to China at the end of 2010. It has also been presented as a component of Abenomics. The TPP negotiations on trade liberalization represent for the Japanese government an opportunity to use external pressures to implement reforms in important domestic sectors such as agriculture, healthcare, and finance. From a strategic viewpoint, the TPP represents a new level of cooperation with the United States, at a moment when tensions may rise further with China, taking into account the very different positions of the two countries in their developmental history and in East Asia's balance of power.

The incentives for the other countries considering to join the Pacific partnership revolve around the eased access to the U.S. market as a supplement to China's, at a time when, after the financial crisis, the United States is experiencing a more robust recovery than is occurring elsewhere in the world. At the same time, the countries in the region seem to share the common strategic prerogative that while it is good to maintain economic ties with China, they need to have strong security ties with the United States. And TPP, through the large set of items being negotiated, is creating the bridge for a new level of coordination between Washington and its partners. A similar dynamic is at play with TTIP for the EU-U.S. relationship.

It is not by chance that both TPP and TTIP became "serious plans" in the very same year. They share an ambitious agenda, involving more than just trading goods. The pacts refer to more structural issues, such as services and investment. The currently negotiated partnerships - covering the Atlantic and the Pacific - are in fact bringing inter-regional integration to a new level, aiming to set a higher bar for all countries interested in doing business with the partners belonging to the club. They add political ingredients to economic interdependencies, making improvements in security coordination possible in the future.

BRICs - the entity formally set up in 2008 (another interesting coincidence on the timeline) between Brazil, Russia, India, and China, and later taking on South Africa in, is being left out of both the TTIP and TPP discussions. The group will ultimately have to decide whether or not to join a market dominated by the two grand partnerships, or to continue developing alternatives to the Bretton Woods institutions.

If the TPP aims to establish a framework for competing against Chinese dominance in the region, TTIP is set to bring Transatlantic relations to a new level, at a time when the European Union is struggling with structural problems and with a resurgent Russia to its east. Considering that China and Russia are likely to enhance their political and economic cooperation in the future, these trade and investment partnerships mean to work as a Western, U.S.-led force for rebalancing global power. The instruments of geo-economics such as productivity, trade balances, or foreign investment are well-linked to military power, geography, and demographics in an era of inter-regional integration and competition - all at work using the realpolitik principles of classic political economy.

Ukraine Seeks Better Battlefield Medicine

As fighting continues in Eastern Ukraine between government forces and pro-Russia separatists, questions swirl in the headlines about the Ukrainian military's readiness and the availability of appropriate equipment. As the situation slowly improves for Kiev, and Ukrainians receive sorely needed professional training and advice, other battlefield issues are just as important as ever. One major issue is medical assistance, and the quality of aid that injured soldiers are getting at the front lines. Ukrainian daily Obozrevatel.ua recently interviewed Col. Yuri Ilyashenko, the chief physician of the Military Medical Clinical Center of the Northern Region, who is currently deployed to fight the separatists in the country's east.

Obozrevatel noted that when the war started in the Donbas region, Ukrainian military doctors were forced to conduct the most operations on the front lines due to a lack of adequate evacuation procedures and logistics. Ilyashenko noted that now, military doctors no longer need to conduct such operations in the line of fire -- their current task has changed to stabilizing the injured and their evacuation away from the fighting:

"We have established integrated systems of emergency care and evacuation. If the distance from the front to the mobile hospital is too great, emergency assistance is provided by medical teams deployed at district hospitals. After surgical intervention and the provision of other kinds of care, the wounded are evacuated either to a military mobile hospital, or directly to hospitals outside the anti-terrorist operations area."

Ilyashenko also noted that soldiers are becoming more familiar with individual medical kits that were initially absent from their personal battlefield equipment. The colonel also assured that almost all soldiers on the front lines have at least three basic items in their medical kit -- a tourniquet, bandages, and painkillers.

Obozrevatel noted that there were many cases during recent fighting where Ukrainian military doctors gave assistance to separatist prisoners, as well as cases when Ukrainian military prisoners received much-needed care in rebel-held Donetsk. Another question asked of Ilyashenko concerned the simple medical goal to save lives, no matter which uniform the injured combatant is wearing. Ilyashenko replied in the affirmative: "If the doctor has honor and conscience, then while he is performing medical duties, his main task is to save lives. It does not matter who is in a hospital bed - a separatist or our soldier. On the other hand, if I was told to treat someone like Hitler -- yes, as a doctor I would perform my duty and do everything to save a life. But when someone like Hitler would be released beyond the threshold of the hospital, and I take off my medical coat, then do not expect from me any mercy and compassion -- as a person and a patriot of Ukraine.

"On the other hand," remarked the colonel, "I know from experience that medical solidarity exists in any political situation. Throughout the year, at different times, two soldiers came to our Military Medical Clinical Center in Kharkov with cases of botulism. Ukraine does not have the serum for this disease and without it, patients could have died. People's lives were at stake, the situation was critical. We therefore reached out via our professional channels to the physicians in the Russian Federation. Russian doctors found the appropriate serum and passed it to us in Kharkov within 24 hours. The lives of these two soldiers - who fought against pro-Russia separatists - were saved."

Presently, all factors point to an uphill but necessary struggle to rapidly modernize all facets of the Ukrainian military, from weapons to medical assistance in battle. Experts point out that Ukraine is working to improve the quality of military equipment in order to meet NATO standards in advance of potentially joining the alliance in the near future.

(AP photo)

Does Europe Have a Plan for What Comes Next?

Even those who welcome the arrival of refugees to Europe are starting to worry. While news media flood their channels with near-apocalyptic images of the refugee onslaught in Europe, emergency asylum centers in many countries seem hardly able to cope. Do their governments have a plan to integrate the newcomers into their societies? The resident populations deserve answers.

As Hungary sends armored vehicles and armed soldiers to meet war refugees spilling over its borders, hundreds of thousands of refugees are arriving in Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Great Britain, and several other nations which have agreed to accept those in need.

While this phase of the refugee crisis -- the arrival -- plays out, polls in the accepting nations are starting to show unease among resident populations. Although many agree that people should be allowed into their countries as they escape war and destruction, increasing numbers are asking what's next for the refugees, and for their own societies.

At the core is anxiety about the difficulty of integrating those refugees who choose to stay. As this poll from the Netherlands shows, 72 percent of respondents expect the newcomers to somehow affect their societies. Fifty-eight percent fear that the refugees will have a negative impact.

The countries now welcoming refugees have already experienced their share of recent socio-cultural upheaval. In most of these countries a perceived failure to fully integrate new minorities into society has led to resentment against established political parties.

As the refugees settle in, the next phase is integration. The past decades have seen severe mistakes made on this front, leading to resentment that has fed widespread anti-immigrant sentiment. The fact that quite a few people firmly believe that every Muslim wants to decapitate unbelievers and hold their wives and daughters as rape slaves doesn't help.

In the past, when countries such as Germany took in large numbers of Turkish refugees, most newcomers were left to their own devices. In many countries this led to the creation of ghettos -- the banlieues of Paris spring to mind. The same thing happened in the Netherlands, where large contingents of Turkish and Moroccan guest workers from the late 1960s onwards weren't bothered with language courses or education programs. As a result, integration for many never happened, and cultural differences remained, much to the ire of many Dutch voters -- some of whom subsequently revolted, adhering to politician Pim Fortuyn when he took a tough stance against newcomers and the country's soft integration policies.

All this raises difficult questions for those in power. Do they have plans for the next phase -- the integration phase? Will there be enough jobs for locals and for newcomers? The German economy needs labor force expansion; the country is greying fast. As this excellent overview by The Washington Post shows, German Chancellor Angela Merkel's open-borders policy is rooted not just in Samaritanism, but also in cold calculus. Germany is heading for major problems down the road because of a quickly shrinking labor force. And right now unemployment in Germany is at record lows. But what happens when the economy goes south again, as economies always do at some point, and unemployment rises?

In the Netherlands and France, unemployment is significantly higher (at 6.3 percent and 10.5 percent, respectively). The Dutch government set aside €900 million ($1.01 billion) to pay for refugees' shelter, and promised still more. Unfortunately, the same government has in recent years made severe cutbacks on benefits for the long-term unemployed and for those on welfare, leading to logical (and tough to answer) questions, such as: Are refugees somehow more important than we, your own resident poor?

The resident populations deserve answers. So the leaders of Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, France -- all those countries that are accepting refugees -- had better devise policies that work, based on decades of experience. That will be the real test of this refugee crisis. Unfortunately, so far governments haven't shown even the beginnings of a plan.

(AP photo)

Electoral Storms Ahead in Europe?

Andy Langenkamp is a global policy analyst for ECR Research.

The Financial Times' Gideon Rachman recently wrote: "At some point, the desperation and hopes of the refugees are likely to collide with the fears and resentments of European voters." The question is whether the outcomes of four upcoming elections will reflect the repercussions of the refugee crisis.

The refugee issue is certainly fodder for populists. Some may tend to the left, with a tendency to campaign against the evils of unfettered capitalism and the free markets. Others rail against immigrants and the threat posed by Islam. However, all of these politicians claim to detest the established order. This is precisely why voters support them.

Greece

I doubt this political trend will turn to triumph at the handful of elections that are due to take place over the coming period. The Greeks come first. On Sept. 20, voters will head to the polls for the third time in eight months. According to most polls, the Syriza party (an amalgam of various left-wing parties) under former Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras leads by a hair. Or, it may have been overtaken by right-wing New Democracy (ND). It is a very close call. Impossible to say which party will come off best on Sunday, but most polls foresee that a combination of pro-euro parties could gain approximately 70 percent of the votes. The chance is slim that the Greek elections will spook the markets. The citizens of Greece know better than most what misery can ensue if a government messes up and antagonizes its creditors. Following Syriza's brief but disastrous period of office, voters will be less keen on a cabinet that incurs the wrath of Brussels and the International Monetary Fund. I am also cautiously optimistic that the elections will help to normalize the Greek situation, because capital controls are slowly being lifted - far earlier than, for example, in Iceland and Cyprus on previous occasions.

Portugal

So the markets are unlikely to cut capers following the Greek elections. Two weeks later, the Portuguese are due at the ballot box. Portugal's incumbent center-right coalition is under fire, and there is a strong possibility that left-leaning parties will take over the helm. Yet the Portuguese bond and equity markets will take this in stride as the major left-wing parties are unlikely to abruptly change course.

Spain

Spanish elections are more crucial. Spain is the Eurozone's fourth-largest economy. In addition, the political system that has been in place since Franco's death - a system that revolved around two parties - could well morph into a multi-party system. Podemos (on the left) and Ciudadanos (on the right) have put the proverbial cat among the chickens. This creates problems for the two traditional parties, the governing conservative Partido Popular (PP) and the left-wing opposition Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE). However, the two relative newcomers may well have peaked too early; they recently lost ground in opinion polls. All the same, they will probably collect enough votes to stop the PP or PSOE from governing by themselves. A grand coalition is a distinct possibility. If so, the markets will be pleased - unless squabbles and watered-down standpoints lead to political paralysis.

Ireland

Ireland will go to the polls in April 2016. The Irish economy is doing relatively well, but many voters fail to feel the effects. This could spell the end for the centrist coalition between Fine Gael and Labour. Theoretically, Sinn Féin could take part in a future coalition government, although the party is increasingly being accused of maintaining closer ties with terrorist IRA and criminal elements than it cares to admit. The party has come a long way and is a mainstream party in many respects, but its left-wing agenda would unsettle quite a few conservatives and businesses. Sinn Féin has clearly indicated it only wants to govern if it is the largest party; this chance appears remote.

If the bookies are right, a coalition between Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil is by far the likeliest outcome. I tend to agree, but there is the potential for two worrying developments. Over the summer, voters increasingly expressed their frustration because they feel that the Irish recovery is benefitting a relatively small portion of the population. This has spawned a general dislike of the political classes, which will provide opportunities to some of the non-traditional parties and independents. Still, I don't think the Irish elections will spoil the market mood.

No electoral thunder

In short, don't expect fierce electoral storms in Europe in the coming months. Occasionally, we could see dark-grey clouds or rain. For example, if the refugee crisis gets further out of hand, or the economic figures prove disappointing. On top of this, looming clouds in Spain should be monitored closely considering the scope of the Spanish economy, the likelihood that the political system will be turned on its head, and the potentially destabilizing effects of the elections in Catalonia at the end of September.

Bibi and Obama Won't Get Along, But Might Now Cooperate

If it swims, quacks, and has feathers, chances are it's a duck. And it's going to stay a duck.

As we analyze President Barack Obama's decision to meet with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu at the White House on Nov. 9, we would do well to remember that.

After seven years of soap opera-style dramatics, Netanyahu and Obama won't change their dysfunctional relationship easily, or perhaps at all.

But as counterintuitive as it may seem, particularly after the bitter battle over the Iran deal, the U.S.-Israeli relationship may actually improve in the months remaining on the president's clock. Obama wants to make nice -- not because he likes Netanyahu or his policies; but because it serves Obama's interests in his final year. Here's why.

Iran: A Unifying Factor? The principal issue over which Obama and Netanyahu have fought may actually bring them closer together now. Obama has beaten Netanyahu on the Iran deal and wants to facilitate the implementation of his key foreign policy accomplishment and preempt Congress's efforts to impose additional sanctions. Netanyahu hates the deal, but he needs to show that his fight with the U.S. administration, while a loss, was still worthwhile.

That means closer cooperation -- both in terms of what the administration will give Israel, and on how the two sides will cooperate to ensure Iran doesn't cheat and expand its influence in the region. If the two can agree on a joint approach -- and each has an interest in doing so -- they may find themselves working together, rather than at cross-purposes. Indeed, Obama cannot afford to become Iran's lawyer, rationalizing its bad behavior away. And Netanyahu has a real interest, particularly now that Russia is supplying military aid to Bashar Assad's regime and perhaps to Hezbollah, in cooperating with Washington to check Iran and its clients. Indeed, once the Israelis start accepting the U.S. goods offered as reassurance for the Iran deal, it will be harder for the prime minister to attack the president's policies.

Why Fight Over the Peace Process? The other area of contention between Obama and Netanyahu is the peace process, and specifically, Israel's settlement activity. Secretary of State John Kerry may want to keep the hope of a two-state solution alive, but the chances of a serious negotiation between Israel and the Palestinians -- let alone an agreement on issues such as Jerusalem or refugees -- are slim to none. Still, as he leaves the White House, the last thing Obama wants is a third intifada, and the same goes for Netanyahu. Whether they can preempt major violence is far from certain. Coddling the Israelis won't necessarily stop Israel's bad policies toward the West Bank. But going to war with Netanyahu over settlements, pushing for a UN Security Council resolution on Palestinian statehood, or joining Palestinians in an effort to isolate Israel, will almost certainly increase Netanyahu's determination to push back. The next year is about keeping the Palestinians and Israelis calm and preventing the Palestinian issue from exploding -- not about resolving it. Unless Netanyahu and Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas find a way to resume negotiations because they both need and want them, keeping the West Bank quiet will be a huge challenge.

Elect a D in the White House: Obama's not running again; but if he wants to increase the chances of getting a Democrat elected in 2016, he will probably want to lower the tension level with Israel. Republican and Democratic candidates will try to outbid each other in declaring their love and support for Israel. This week's Republican debate had at least half a dozen candidates doing so, and hammering Obama on what the Republicans see as his anti-Israeli policies works as a campaign issue. Not ceding the Israeli issue to Republicans, particularly if Hillary Clinton is identified closely with the Iran deal, would be smart politics for the Democrats. The Republicans would love for the next year to see a continuing crisis between a Democratic president and an Israeli prime minister.

Obama Needs all the help he can get in his final year: A year and two months from now we will have a new president. And this president will address a Middle East in far worse shape than the one Obama inherited. Forget new breakthroughs. Israel remains critically important to the administration's efforts to avoid breakdowns -- on Iran, the Palestinians, and even in Syria now that Russia has upped the ante. Bottom line: President Obama doesn't need a war with Bibi. He doesn't like the prime minister, hates his policies toward the Palestinians, and remembers his efforts to sink the Iran deal. But the president wants to avoid leaving the presidency with the Middle East in still worse condition. And that means counting to ten before exploding, and trying to work with a difficult and frustrating Netanyahu rather going to war with him.

(AP photo)

Russia Thinks the U.S. Is Pushing Refugees Into Europe

So that there can be no doubt about how some in Russia feel about the refugees from Syria and Iraq surging into Western Europe, Komsomolskaya Pravda's Daria Aslamova published an op-ed laying the responsibility squarely on the United States.

KP is a frequent platform for anti-Western and anti-American sentiment and often gives voice to Russian officials' thoughts on their nation's foreign and defense policies.

"Let's just answer the question", begins the op-ed, "of why migrants from the Middle East are not interested in staying in Hungary, Greece or Serbia. Because these countries are considered quite poor! The migrants are amazed. They did not expect to see people in Europe living so poorly. In Syria and Iraq before the war, people lived much better than they do now in Serbia or Macedonia. Even more than in Greece, which is now trying to save on everything. Migrants are wondering what to do in Southeast Europe. Serbia, for example, was ready to give refugees a residence permit and the right to asylum, but have given them only to 14 people, because no one asked. They want to go right to Germany, where they get good unemployment benefits.

"Today's refugees are rich people," continues the paper. "Because not everyone can afford such an expensive relocation. Where do they get the money? As it turns out, they get help from many American charities. Interestingly, we note that every morning near the banks there are huge queues of migrants, they receive money in every city where they arrive -- in Belgrade, Budapest, and Athens. Therefore someone forwards them money throughout their journey. Question -- who does that? Partially, as it turns out, it's the Americans."

The columnist goes on to explain her view that America wants the refugees to go Europe, further speculating on how "strange" it is that so many people have tried to access the Continent at the same time, and adding that "someone" promised them mountains of gold.

"You have a huge mass of people," continues KP. "The first are the Iraqi masses, fleeing from ISIS atrocities. The second mass fled Syria -- also from ISIS. Just in Lebanon, with a total population of 4 million, there are an additional 2 million Syrian refugees living in appalling conditions. This whole multitude of refugees began to put pressure on Turkey, and Turkey started to push them out. Where to? Only toward Greece, since getting into a boat gets you to Greek islands in couple of hours.

"A larger picture emerges out of this puzzle," concludes Aslamova. "It becomes clear that the USA is planning the occupation of Europe via Turkey and its charities."

KP also recently interviewed Middle East expert Elena Suponina, the advisor to the director of the Russian Institute for Strategic Studies, on the question of whether Russia should share Europe's concern over the refugees.

"Firstly, some migrants from the Middle East are already using Russia as a transit territory to get to Europe, " Suponina said. "Secondly, some groups of refugees from Syria -- for example, of Circassian origin -- are settling in the North Caucasus among fellow Circassians, so we already have Syrian refugees, although not in such great numbers as in Europe and some Middle Eastern countries.

"This is not the most urgent problem for us right now. This threat is more indirect -- refugees settling in Europe, causing numerous social problems, as well as terrorism and radicalism. So the Russians may be faced with migrants while traveling abroad, but not at home."

Suponina then explained her view of why Russia is not a chosen destination for refugees:

"In general, Russia is not very attractive for people from Middle Eastern countries. We do not want them to linger, because here they are not promised fat social benefits as in Europe. In Russia, immigrants have to work to survive. In addition, these migrants have great difficulty with the language barrier -- in Europe, they can communicate in English. Additionally, our immigration and visa laws are stricter than Europe's, and Russia is far away geographically. Finally, our climate is more harsh for the southern people."

Exodus and Redemption

Is there a useful analogy to make between the streams of Syrian refugees and the Biblical Israelites? After all, analogy is the weakest form of proof. It only means that this seems to be like that, and the notion can be mistaken, the comparison far-fetched.

At first judgment, nothing seems to justify comparing the two. Syrians now streaming into Europe are leaving their own country, a land where their roots as a civilization go back 3,000 years to the first Assyrian Empire. Syrians have always had a country, whereas the Israelites, later known as the Jews, did not until the creation of Israel in 1948. Old Testament Israelites, led by Moses, escaped from Ancient Egypt, where they were new arrivals, a tiny foreign people that had been enslaved by the pharaohs.

Yet there remains something right in the comparison of today's Syrians and Biblical Israelites. That something is the concept of Exodus; an enduring theme in the history of human civilization. Syria today represents the world's greatest humanitarian tragedy. It pales before what happened to the Jewish people in the Holocaust, but the Syrians fleeing their own country and their refugee camps in Turkey, Jordan, and elsewhere, constitute a contemporary Exodus. Resettling them is more than a policy issue of how to divide them among various European Union countries as a problem of burden-sharing.

Thinking of the situation against the story in the Bible inspires a sense of common humanity about the Middle Eastern morass, rather than seeing it as just a war against the Islamic State, the regime of Bashar al Assad, al-Qaeda, and other marauding bands of thugs as reported in the media. This is a story that could be recorded in some future great book, written not by God but by historians. Syrian Exodus (leaving aside the thousands of opportunistic, carpe diem refugees with other origins and reasons) is an escape from hell. If empathy prevails and analogy is admitted, it could influence modern Middle Eastern history. Secular antagonisms between Sunni and Shiite Muslims, and the Islamic State's murderous intention to pulverize stones, monuments, and people in an attempt to destroy everyone else in a Sunni Muslim conquest, will be seen for what it is: a dishonoring of Islam as a religion and of Muslims as a world community of believers. Perhaps even attitudes toward the Jews and Israel will be affected.

For the Syrians -- even for those who still remain -- their own country has become "Egypt." Dealing with their situation is not a matter of foreign and domestic policies. It's an international reckoning with historic collapse at the center of the Arab Muslim world. The consequences are geopolitical, geo-social, geo-emotional.

Syrians will be a new fact on the ground in Europe as well. For many months shunned by European governments, their appeal for asylum is suddenly being accepted as a humanitarian and moral duty impossible to ignore. Syrians will become small but perhaps significant minorities in a few European countries. Pope Francis, who has stepped out from papal reserve in so many ways, implores Europe's Catholics to welcome the migrants. European Union officials are no longer deadlocked; they must deal with what they can no longer avoid.

The issue of German Redemption

Then there is the significance of German leadership in accepting the Syrian asylum seekers into the European Union. For Germany in particular, government and civil society's welcoming of Syrian refugees continues the country's quest for redemption from the unspeakable crimes of their grandparents and great-grandparents. The German people's attempt at redemption is a secular cause played out on a Biblical scale, because the Holocaust was a crime against not only humanity, but against human civilization itself. For religious believers, it was a crime against God. In some sense, "Germany" may never redeem its crimes, but "Germany" is not today's German people, difficult as that may be for some people to accept.

Germans for decades shied away from international political leadership. Its leaders made of Germany's economic success and generosity in financing European integration (plus its unyielding political support of Israel) the basis of its international influence. During these decades Germany's foreign economic generosity was its foreign policy. With the French, Germany organized the complexities of the European Union's internal contradictions into a vision of Europe's renewal, the possibilities of resurrection. German money underwrote France's political leadership. The two countries produced leaders of vision on the scale of history: Konrad Adenauer and Charles de Gaulle; Helmut Kohl and François Mitterrand. Today no other country's political and business elites, not even those in France, are thinking as deeply as Germany's about how to move European integration forward in a strategy that combines national interests and Europe's necessities. Germany's partner countries want more rather than less German leadership, an astonishing international recognition of redemption. Germany's willingness to accept large numbers of refugees is only the most recent act of this attempt to prove that the "German problem" is history.

Accepting large numbers of refugees is also good for Germany itself. Along with Europe's other demographically withered countries, Germany, whose birth rate is among the lowest in the world, needs significant immigration to finance its future, while doubters and racism have rendered it thus far impossible. From the point of view of German interests, Syrians (and many opportunist refugees) are an educated population, willing, indeed desperate, for jobs and acceptance. Ties to the Syrian homeland will remain strong, but gratitude to Germany will be real. America's experience, despite current electoral posturing, shows that immigration is a boon to national vibrancy. Why not for Germany and Europe as well? Furthermore, a significant Syrian minority population will increase social pluralism, among other things diluting domestic focus on Germany's Turkish minority.

A few hundred thousand or even a few million new immigrants won't solve Germany's or Europe's demographic problems. But the irrepressible urgency of the current refugee crisis is accomplishing what politics failed to do -- lancing a boil, unlocking a self-defeating national stalemate. In contrast, Germany's reception of hundreds of thousands of asylum seekers fleeing former Yugoslavia's wars in the 1990s was not an economic necessity, because the demographic deficit was not so evident then. Taking in Croats, Serbs, Bosnians, and others was a political act of redemption and, for Germans themselves, an act of national catharsis. Yet strong internal opposition to immigrants did not abate.

Accepting Syrians inevitably increases the need for German leadership in Europe's response. Germany's government, led by the indomitable Mrs. Merkel, is stepping up to the task successfully. (It will accept at least 800,000 asylum seekers in the coming year, far more than any other EU country and probably not the end of what Germany will do.) The trouble with German redemption, however, is that dealing with a problem may not solve it but increase it. I often wondered during years of teaching European politics how long the German Problem would endure, at least in people's minds. When would redemption be complete? I don't know the answer, but at a certain distance from the event, history makes such questions irrelevant.

(AP photo)

The Chasm Between Russia and the West

Dinesh D'Souza did a good job in his movie, America, explaining how the Western world moved over a long stretch of time from a culture of conquest to one governed by the rule of law.

That is a journey Russia never made.

There remains a canyon of difference between Russia's culture and that of the West. If ever there was a real deficit of understanding between two peoples that could lead to war, this is it. It reminds me of the Yangs and the Coms, of Starfleet measuring up with the Klingons.

Russian culture suffers to this day from the effects of centuries of rule by the Golden Barbarian Hordes of Middle Asia. When the likes of Ghengis Khan arrived at your city, the first thing they did was to kill most of you - then they enslaved the rest. A governmental system of strongmen was set up to whom you had to pay homage and tribute. This system still exists in Russia today. Outside a brief flirtation with democracy in the 1990s, it never changed.

Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper was right when he said Russia doesn't share Western values. That is no secret, but the greater point is, they don't want to share Western values! Did you know that Russia last year imported more than half a million baseball bats? It's not that baseball is a Russian's favorite pastime. No, Russians love to use them to settle traffic disputes.

America was settled mainly by the English and benefits from the English rule of law. Any country that was part of the English Crown has this heritage. This has never before existed in Russian history.

Ivan the Terrible, the famous Russian tsar who is buried in the Kremlin, killed his own son, and had a bad habit of frying his opposition in huge frying pans, took this tribute system a step further. He organized a group of wealthy power brokers around him. He kept them satisfied, and in return they protected his power. They were called the Oprichnina, and they terrorized tsarist Russia. How different was that set from the group of oligarchs and state security services keeping Russian President Vladimir Putin in power?

Russia doesn't have the death penalty because people are afraid that those in power will send their adversaries to the gallows on trumped-up charges. The federal tax agencies are a favorite tool of the ruling set to go after the political opposition.