Israel, Iran and Red Lines

Earlier this week, the News Hour hosted an interesting discussion between Robert Satloff and Paul Pillar on the Iranian nuclear program and Israel's "red lines." Enjoy.

« August 2012 | Blog Home Page | October 2012 »

Earlier this week, the News Hour hosted an interesting discussion between Robert Satloff and Paul Pillar on the Iranian nuclear program and Israel's "red lines." Enjoy.

Yuir Yarim-Agaev is worried about America's approach to radical Islam:

The winning formula against Soviet communism proved to be peace through strength. A strong military and economy are important, but even more important is standing strong for basic principles. Ronald Reagan, Pope John Paul II, and the Soviet and East European dissidents all understood this.We did not start wars with communism, Nazism or Islamism. They were imposed upon us. Those ideologies thrive on confrontation with the free world. Today we must revisit Kristallnacht, the Holocaust and the Cold War, to recollect our successful experience of dealing with those virulent ideologies.

The fact is, empty slogans like "peace through strength" are not only not applicable - they're patently absurd. The U.S. is exponentially stronger that any combination of Islamist foe and will only grow stronger if societies like Egypt embrace fundamentalism (given it's rather abysmal record in governance).

Those who preach the superiority of Western values should have a bit more confidence in their long-term prospects.

Now, if you really want something to worry about, may I suggest this?

Joshua Foust makes some good points pushing back against the Living Under Drones report, noting that the methodology was designed to produce a somewhat skewed report:

For starters, the sample size of the study is 130 people. In a country of 175 million, that is just not representative. 130 respondents isn't representative even of the 800,000 or so people in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), the region of Pakistan where most drone strikes occur. Moreover, according to the report's methodology section, there is no indication of how many respondents were actual victims of drone strikes, since among those 130 they also interviewed "current and former Pakistani government officials, representatives from five major Pakistani political parties, subject matter experts, lawyers, medical professionals, development and humanitarian workers, members of civil society, academics, and journalists."The authors did not conduct interviews in the FATA, but Islamabad, Rawalpindi, Lahore, and Peshawar. The direct victims they interviewed were contacted initially by the non-profit advocacy group Foundation for Fundamental Rights, which is not a neutral observer (their explicit mission is to end the use of drones in Pakistan).

Foust also asks an important question: if not drones, what? When the Pakistani army attempted to clear militants from the FATA, it resulted in massive destruction and tens of thousands of refugees - far worse than the toll inflicted by U.S. drones.

But does this mean the drone program, in its current form, is the "only" choice? Foust thinks so:

The targets of drone strikes in Pakistan sponsor insurgents in the region that kill U.S. soldiers and destabilize the Pakistani state (that is why Pakistani officials demand greater control over targeting). They cannot simply be left alone to continue such violent attacks. And given the Pakistani government's reluctance either to grant the FATA the political inclusion necessary for normal governance or to establish an effective police force (right now it has neither), there is no writ of the state to impose order and establish the rule of law.

But here's the thing: how many drone strikes are targeting international terrorists (i.e. those training or plotting to hit U.S. and Western targets abroad) and how many are hitting local insurgents who are fighting the U.S. because it's decamped in Afghanistan?

This seems like a critical distinction (although these two militant groups likely collaborate) because one group poses an enduring threat to the United States and the other ceases to be an American problem once Washington abandons its flailing nation building effort in Afghanistan. From publicly available information, it's not always clear which of these groups is being targeted. The tempo of the drone strikes suggests that it's less about hitting international terrorists and more about extending the Afghan war into the Pakistani sanctuaries that are out of reach of U.S. troops.

That leads to a second, far more important, question: is the U.S. targetting militants that threaten the Pakistani state, or those sponsored by the Pakistani state. It's rather perverse to argue that drones are critical to protect Pakistan from militant violence when that country's intelligence service believes it is at war with you and uses militants to advance its own interests.

Underlying these questions is a somewhat understandable/somewhat troubling lack of clarity (and outright falsehoods) from the Obama administration as to what's going on. While much of the concern over the drone war comes from questions about its effectiveness (or lack thereof) in curbing terrorist violence, we should be equally concerned about how the use of this weapon is enshrining some of the worst tendencies in Washington with respect to democratic accountability and the rule of law.

(AP Photo)

A new report, Living Under Drones, goes on the ground in Pakistan to document the U.S. drone war. I've just started reading it, but the above teaser video does a good job setting up the overall thrust. Long story short: the U.S. line on drone strikes as being surgical appears to be vastly overstated.

Here's the pitch:

In The Canada Party Manifesto: An Intervention From You Continental BFF, which was published last month, authors Brian Calvert and Chris Cannon – and Vancouver residents – continue on their satirical prescription for an ailing America.Featured in U.S. and Canadian media – including CBC’s The Current earlier this week – their lighter take on the presidential election is attracting a wider audience. A video feature about the group on the BBC news site topped the site’s most-watched video list on Thursday.

The party promises American voters: “One gay couple will be allowed to marry for every straight couple that gets divorced.

“The phrase “job creators” will be changed to “job creationists,” and they will be given seven days to actually create some.

“Corporations will still be people, but if they can’t provide a birth certificate they will be legally obligated to care for your lawn."

We've heard a bit in recent days about how Japan's security establishment is drifting to the right - becoming more assertive over its claims to disputed Islands also claimed by Russia and China.

But as Justin Logan points out, nationalist bluster aside, Japan is actually cutting its defense spending. Moreover, in response to the U.S. pivot, China is upping its own defense budget. These are two trend lines moving in the wrong direction.

Of course, the U.S. taxpayer is on the hook, as Logan notes:

So if Japan’s leaders are getting increasingly concerned about security, why are they cutting defense spending? Simple: They believe that they have a defense commitment from the United States that can serve as their deterrent against China.So when you hear members of Congress rending their garments about sequestration, remember what they are worried about: the prospect that the transfer payments from American taxpayers to taxpayers in places such as Japan may be trimmed.

When the U.S. consulate in Libya was attacked, information was obviously in short supply. It's understandable that the Obama administration would not instantly have all the facts at its disposal and so revisions of earlier statements (such as Susan Rice's insistence that the attack was a spontaneous reaction to that idiotic movie) were to be expected.

But in Washington, admitting mistakes - a perfectly human and rational thing to do - simply isn't done. And so we have the increasingly sad spectacle of the Obama administration's furious spinning over Libya, which culiminated in this embarassing (for both parties) email exchange between reporter Michael Hastings and Secretary Clinton's spokesman.

This kind of dysfunction isn't new or unique to the U.S., but it's still depressing.

When the Bush administration sought to tie the regime of Saddam Hussein to terrorism, it pointed to the sheltering of the cult/terrorist group Mujahedin-e-Khalq Organization (MEK) as one of its transgressions. Last week, the Obama administration decided to pull the group from the State Department's list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations, despite concerns that they're still in the terrorism business. The ostensible reason the group was removed was because they complied with a U.S. request to depart Iraq, but Paul Pillar notes that it sends an unmistakable signal to Iran:

No good will come out of this subversion of the terrorist-group list with regard to conditions in Iran, the behavior or standing of the Iranian regime, the values with which the United States is associated or anything else. The regime in Tehran will tacitly welcome this move (while publicly denouncing it) because it helps to discredit the political opposition in Iran—a fact not lost on members of the Green Movement, who want nothing to do with the MEK. The MEK certainly is not a credible vehicle for regime change in Iran because it has almost no public support there. Meanwhile, the Iranian regime will read the move as another indication that the United States intends only to use subversion and violence against it rather than reaching any deals with it.Although the list of foreign terrorist organizations unfortunately has come to be regarded as a kind of general-purpose way of bestowing condemnation or acceptance on a group, we should remember that delisting changes nothing about the character of the MEK. It is still a cult. It still has near-zero popular support in Iran. It still has a despicably violent history.

New America's Barry Lynn argues that the Obama administration's China strategy makes no sense:

The Obama administration, over the last year, has chosen to pursue both of these extreme -- and opposed -- options. On the one hand, it has begun to devote real energy to a new generation of trade agreements, like the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which aim to tie the U.S. and Chinese economies together even more closely. On the other, it has begun to meet force with force. As Beijing blusters in the South China Sea and builds up military power, Washington has dispatched Marines to Australia, promised a new missile shield to Japan, and proposed to station a second carrier group in the region.This is absurd. To tighten the gears of the international production system and, simultaneously, to position more heavy weapons right on the factory floor is a recipe only for catastrophe. Any conflict of any size would almost instantly break many of our most vital systems of supply. Instead, the United States should use its power to force corporations to distribute production capacity more widely. Such a move would reduce China's growing leverage over America -- and it would help stabilize the international system, economically and politically.

Lynn goes on to make the case that diversification of industrial production is what will ultimately guarantee U.S. security:

The only real option is to embrace the logic of industrial interdependence, hence to recognize that the only way for the United States to achieve its most vital national aims -- indeed, to be taken seriously by China -- is no longer to reposition its aircraft carriers, but to force its industrial and trading corporations to reposition the machines on which it depends. The United States does not need to bring all or even any of these systems of production home. But it can no longer continue to live in a world in which many activities remain in one location, under the control of one state, especially a strategic rival.

It's interesting that one of the consequences of shifting China into the "strategic competitor" basket is that it may force the U.S. to sideline free market orthodoxies.

Every foreign policy dogma suffers from its own conceits. For neoconservatives, it's the idea that military force and demonstrations of "will" can routinely produce favorable policy outcomes around the world. For the Democratic foreign policy establishment, one guiding conceit is arguably the notion that a more globally popular America will allow a largely identical series of policies to be accepted much more happily. These are generalizations, of course, but I think they largely fit the bill.

Just as the Iraq war exposed the limits of the neoconservative doctrine, the riots engulfing the Middle East have surely revealed the fallacy of the global popularity doctrine. Because, as Richard Wike explains, it's difficult to improve America's image without actually changing American policies:

Why hasn't America's image improved? In part, many Muslims around the world continue to voice the same criticisms of U.S. foreign policy that were common in the Bush years. U.S. anti-terrorism efforts are still widely unpopular. America is still seen as ignoring the interests of other countries. Few think Obama has been even-handed in dealing with the Israelis and the Palestinians. And the current administration's increased reliance on drone strikes to target extremists is overwhelmingly unpopular -- more than 80 percent of Jordanians, Egyptians, and Turks oppose the drone campaign.The opposition to drone strikes points to a broader issue: a widespread distrust of American power. This is especially true when the United States employs hard power, whether it's the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq or the drone attacks in Pakistan, Somalia, and Yemen. But it is true even for elements of American soft power. Predominantly Muslim nations are generally among the least likely to embrace U.S. popular culture or the spread of American ideas and customs. Only 36 percent of Egyptians like American music, movies, and television, and just 11 percent believe it is good that U.S. ideas and customs are spreading to their country.

The crisis between China and her neighbors over a series of contested islands has been steadily ratcheting up. Duong Huy does a deep dive into the legal basis for China's broad claim and finds it wanting.

James Joyner thinks so:

That the war in Afghanistan has been unwinnable has been obvious to most outside analysts since well before the so-called surge of 2009. Now, the United States government has finally admitted the obvious in deeds if not words.Following the murder of six NATO troops in yet another "green on blue" attack in which Afghan soldiers supposedly fighting on our side killed NATO troops, the coalition has all but ended combined operations with Afghan army and police forces at the tactical level, requiring general officer approval for exceptions.

While spokesmen insisted that "we're not walking away" from the training and advisory mission that is the ostensible reason for continued Western presence in Afghanistan eleven years into the fight there, that statement rings hollow. As American Security Project Central and South Asia specialist Joshua Foust puts it, "The training mission is the foundation of the current strategy. Without that mission, the strategy collapses. The war is adrift, and it's hard to see how anyone can avoid a complete disaster at this point."

As Joyner notes, it would be nice if the presidential contenders could spare a few minutes to sketch out their thoughts on what U.S. policy toward Afghanistan is going to look like going forward.

The ongoing protests over the anti-Islamic film "Innocence of Muslims" has naturally led to finger pointing and partisan sniping in the United States.

On the left, we have the absurd (and evidently untrue) suggestion from the Obama administration that it was all just outrage over "Innocence." Just a misunderstanding that can be soothed over with more pious homilies. Conservatives have responded by retreating to the usual trope that "strength" will be respected and that it was simply Obama's weakness that initiated the ferocious unrest.

The truth is, the U.S. has a very immature relationship with the Middle East. The left and neoconservative right tend to treat the region as child-like, in need of careful nurturing so that they can flower into their full democratic potential (and be ever grateful as a result). The right, when not indulging in the same democratic do-gooderism, tends to believe that the region is similarly child-like but needs to be cowed with displays of power, the better to "respect" us (translation: submit to policies they find offensive or oppressive). Both sides routinely express shock and outrage when the Mideast responds with displays of anti-Americanism.

Moreover, despite some topical changes, U.S. policy toward the region has been incredibly stable since President Carter: the U.S. takes a deep and abiding interest in keeping Israel secure, anti-American powers down, and corrupt and dictatorial allies in power. All three policies are deeply resented in the region. To a subset of the region, American values aren't that popular either (even a wholesale change in U.S. policy wouldn't stop Salafist rabble rousers from burning flags and marching on embassies at this or that perceived outrage, nor is it likely to stop dedicated jihadists whose radicalism can't be wound down all that quickly).

So the likely U.S. response to Middle Eastern protest, in the short term at least, is going to be more of the same. Conservatives will make vague but insistent demands for "strength" while liberals will talk up the merits of outreach and democratic reforms. Foreign policy experts will double down on the orthodoxy that the Mideast is just too important to be left to chart its own destiny.

I'd prefer to see these events as yet another reminder that the U.S. should be pursuing a policy of gradual disengagement and benign neglect. Over time, if fracking and alternative energy sources ultimately do disperse the concentration of strategic energy wealth around the world, the value of the Middle East to U.S. economic security will plummet (indeed, it was arguably overblown to begin with). That will knock the legs out of the rationale for supporting what dictators and monarchs are able to pull through the Arab Spring. It will also weaken the rationale for attacking countries like Iran, whose principle threat to the U.S. revolves around an ability to spike global oil prices. Washington's ability to secure Israel will suffer a bit with fewer dictators to bribe, but Israel's defensive capabilities can still be sustained offshore - through arms sales and intelligence sharing.

(AP Photo)

Jonathan Tobin is unhappy with how the debate over Iran's nuclear program is playing out:

But this argument isn’t so much about what will happen in November, as it is a not-so-subtle effort to silence a reasonable critique of American foreign policy by both Israelis and their American supporters. In doing so, some on the left are seeking not so much to bolster President Obama as they are to delegitimize the notion that the United States ought to be listening to Israel’s warnings about Iran in a manner highly reminiscent of the “Israel Lobby” conspiracy theories. [Emphasis mine]

I don't believe this is quite right. No one is saying that the U.S. government shouldn't "listen" to the Israelis - that seems like a rather absurd position. Of course the U.S. should listen to the Israelis. Israel has vital intelligence on these matters and has an important perspective - no serious person would deny that they have a right to be heard on the issue. The objection is that the U.S. shouldn't have to align its policies and rhetoric to accord with the current Israeli government on the Iran issue - and that a failure to reach alignment isn't a sign of moral failure.

Right now, the positions of the U.S. and Israeli governments are different. It's perfectly fair for people to complain that the U.S. has it wrong and the Israelis have it right, but it's perfectly fair to argue the reverse. I think Tobin is right to suggest that the idea that Romney has "outsourced" his foreign policy to Netanyahu is crude and demagogic. If Romney is wrong (or right) about how to handle Iran, his arguments need to be dealt with on their merits - not on whether or not they correspond with another government's views on the matter.

But it's just as demagogic to insist that disagreeing with the Israeli position on Iran is somehow un-American, as Tobin does in the very same piece:

By pointing out Obama’s mistakes, such as the years wasted on engagement with Tehran, the delay in enforcing sanctions as well as the president’s seeming to have a greater interest in restraining Israel than in pressuring Iran, Romney isn’t undermining U.S. sovereignty. Nor is his willingness to allow Israel the right to defend itself a case of the tail wagging the dog.In doing so, Romney is merely reasserting a traditional American position. [Emphasis mine]

In addition to implying that the reverse is an un-American position, it's a curious reading of the "traditional American position." Looking at the broad history of U.S. foreign policy, I'd say there has been an equally robust tradition that has been wary of entangling alliances.

The injection of politics into the discussion was bound to drive the question of how to handle the Iranian nuclear program into the fever swamps. It appears we've arrived.

If the Arab spring turns into an “Arab winter,” as Romney put it, and tumult spreads across the region, a backlash could certainly build against Obama’s handling of the uprising, leaving Romney to profit politically. - Alex Altman

It's unlikely that such a critique would need to be coherent to actually work politically, but it's still worth asking where it is that Obama supposedly fell short. Yes, the statement out of the Cairo embassy was ridiculous and mealy mouthed. The U.S. should never have apologized for a film, no matter how puerile and inflammatory. But the charge that President Obama has "mismanaged" the Arab Spring makes one huge assumption and one deeply absurd one.

The huge assumption was that there was a series of policy options available to President Obama that would have avoided these attacks on American embassies. That's doubtful. Under the best of circumstances, the U.S. can't ensure a 100% defense against terrorist attacks - which is what the Libyan tragedy appears to be (not the work of raving fundamentalists, although they provided the cover). The legacy of anti-Americanism and fundamentalist rabble-rousing is also rather entrenched in the Middle East at the moment and it's not clear what Obama was supposed to do to alleviate that over the last two years.

Moreover, how should the administration have reacted to the various uprisings? Should Obama have insisted that Mubarak and Gaddafi stay in power lest the forces of radicalism overwhelm the region? (But then he'd be betraying American values, wouldn't he?) Should he have waved a magic wand and turned states that suffered under decades of corruption, mismanagement and autocracy into functioning, stable, pro-American democracies?

Undoubtedly, the administration has slipped up in its handling of the Arab Spring; it's a momentous, historic event that caught the U.S. largely off guard. But this leads to the absurd assumption implicit in the criticism of the administration: that the U.S. federal government can deftly finesse the direction of Middle East politics in the 21st century. Particularly for those who profess a love of "limited government" it seems rather farcical to claim that the same incompetent government that can't be trusted to balance the budget can reach across the ocean and create a Middle East more to its liking.

Yet in the clown show of contemporary politics, it's enough to lob a series of incoherent criticisms into the air and call it a day.

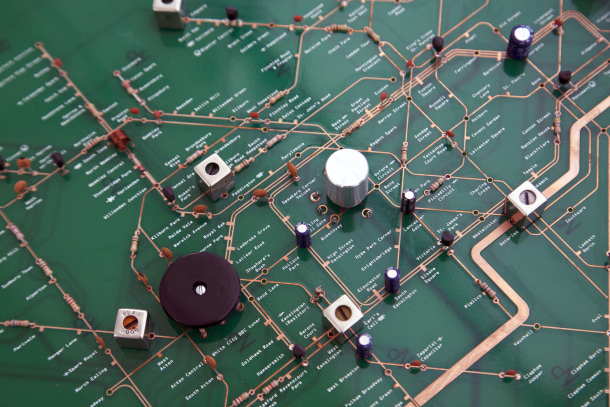

Artist Yuri Suzuki built the radio circuit board above to match the layout of the London underground.

(Hat tip: Leslie Katz)

Jennifer Rubin uses the anniversary of 9/11 to take a partisan jab at President Obama:

It is distressing when we observe the lethargy and unseriousness with which we address national security. Eleven years after 9/11 we learn the president skips half of his intelligence briefings. Congress and the president have set in motion national security cuts that longtime Democrat, Defense Secretary Leo Panetta, has dubbed “devastating.” We learn that the White House came up with the sequestration gimmick to try to force Republicans to raise taxes; there is no sign the president will intervene in sufficient time to halt substantial layoffs in the defense industry. Is this the same nation that rallied to the defense of the West? It’s hard to believe sometimes.We are light-years away from the Bush administration, to be sure, when George W. Bush “held his intelligence meeting six days a week, no exceptions — usually with the vice president, the White House chief of staff, the national security adviser, the director of National Intelligence, or their deputies, and CIA briefers in attendance.

This is a weird critique to make. Certainly, President Obama's counter-terrorism record is far from perfect, but, good or bad, sequestration and defense industry layoffs are unlikely to impact U.S. counter-terrorism (as defined by intelligence collection, analysis and the drone campaign - not nation building in remote regions). Most of the very controversial legal infrastructure around the war on terror remain in place. When it comes to targeting al-Qaeda, President Obama has been as aggressive - if not more so - than President Bush. Just yesterday, a senior al-Qaeda figure in Yemen was killed, likely by a U.S. drone. As former Director of the CIA Michael Hayden recently observed, there has been "powerful continuity" between the Bush and Obama administrations when it comes to counter-terrorism, with the exception being that the Bush administration was heavier on the torture and the Obama team leans more on assassinations.

Moreover, while it's true that President Obama should attend more intel briefings, why Rubin would choose this angle is odd, given that when President Bush enjoyed those briefings, he dismissed terror warnings before 9/11 and reportedly told a briefer who warned about potential al-Qaeda attacks on the homeland that he had "covered his ass now."

Rather than focus on partisan non sequiturs like the potential impacts of sequestration, the real legacy of 9/11 is just how resilient al-Qaeda has proven. Bruce Reidel paints a stark picture:

Eleven years after 9/11, al Qaeda is fighting back. Despite a focused and concerted American-led global effort—despite the blows inflicted on it by drones, SEALS, and spies—the terror group is thriving in the Arab world, thanks to the revolutions that swept across it in the last 18 months. And the group remains intent on striking inside America and Europe....But it is in the Arabian Peninsula that al Qaeda is really multiplying. Its franchise in Yemen has staged three attacks on America, including one at Christmas in 2009—the infamous “underwear bomber—that almost succeeded in Detroit. Its brilliant Saudi bomb maker, Ibrahim al-Asiri, is alive and has trained a cadre of students. The Yemeni regime is weak, the country is spinning into chaos, and al Qaeda is exploiting it. Now the U.S. is using drones almost as much in Yemen as in Pakistan.

The al Qaeda apparatus in Iraq, despite being decapitated several times, carries out waves of bombings every month. It has proven remarkably resilient. In North Africa, al Qaeda has allied itself with other Islamist extremists and taken over more than half of Mali, an area bigger than France. There it is training terrorists from Algeria, Morocco, Nigeria, and elsewhere. It has raided Muammar Gaddafi’s arsenal and is armed and dangerous.

A new al Qaeda franchise has emerged in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, where it is trying to provoke a war between Egypt and Israel. American troops in the multinational force keeping the 1979 peace treaty are at risk.

The fastest-growing al Qaeda operation is in Syria.

The toppling of Saddam Hussein and the revolutions that have unseated autocratic rulers have done a lot of bin Laden's work for him.

(AP Photo)

In response to a plan to hike taxes on wealthy individuals, France's richest man, Bernard Arnault, has filed for Belgian nationality.

The French left has gladly offered to hold the door open for him. The headline above, from the left-wing daily Liberation, reads: "Get lost, you rich bastard."

Daniel Trilling provides some context:

The headline is actually a play on a famous gaffe made by the former president, Nicholas Sarkozy, who muttered "casse-toi, pov' con" ("get lost, you poor bastard") at a member of the public who refused to shake his hand. The phrase subsequently became a taunt taken up by Sarkozy's left-wing opponents.

One persistent criticism of Mitt Romney's foreign policy is that he has yet to distance himself from the Iraq war. Jordan Michael Smith (via Larison) offers a typical complaint:

The GOP wants the public to forget that Republicans got America into a disastrous, unnecessary war, of course. But the larger problem is that conservatives simply have not acknowledged the failure they unleashed in Iraq, let alone learned from it. To judge both from Mitt Romney’s rhetoric and his advisors’ track records, when it comes to foreign policy, a Romney administration would be a second Bush administration.

Often critics of the Iraq war write as if it was self-evidently a mistake and that the Republican party establishment will somehow be forced to come to grips with it. Certainly, a majority of the American public thinks the Iraq war was a mistake, but what they think really doesn't matter that much (it could, potentially, if Congress asserted a more active role in these matters, but that's not something they care to do). The truth is that the Iraq war is slipping (if it hasn't already) the bounds of objective reality and entering a realm of partisan positioning.

Many of those advising and supporting Governor Romney's campaign not only think the war was the right thing to do, they think it was largely a success. Furthermore, because the Democrats have, brazenly, evaded their share of responsibility for voting for and endorsing the Iraq war, and have instead painted themselves as the war's skeptics and critics (which, to be fair, some were from the outset) they have reinforced a Republican tendency to circle the wagons on Iraq.

So it's no surprise that Romney and his advisers won't offer a mea culpa for Iraq, since they don't believe it was wrong and because such an admission would invite negative political consequences.

This leaves us with one political faction that believes the lesson of the Iraq war was that it was a good idea and something to replicate in the future - likely with Iran, and another that doesn't have a strong position one way or another but will gladly tack in whatever direction political expediency points to.

Ordinarily you'd be forced to conclude that no superpower could continue in this manner for very long, but when most of your potential challengers are equally dysfunctional (or even more dysfunctional), there's really little external pressure to get your act together.

Irvin Studin thinks so:

A similar dynamic to that in the South China Sea may well develop before long in the Arctic, where at least five countries – the US, Russia, Canada, Norway and Denmark – are scrambling for position as the polar ice melts at ever-accelerating rates. China, while not yet a first-order Arctic player, is very much alive to this situation. It and other big players, including India and the EU, will want in. The ambitions of the actors in this theatre may soon be at odds with the prevailing “Pax Arctica” doctrine that claims, at least publicly, that the international rule of law, prudence and co-operation will govern the judgment and behaviour of all players for the foreseeable future.In the coming decade or two, once the polar ice has melted, use of the Northwest Passage will reduce travel distances between Asia and Europe by up to 7,000km. The aggregate hydrocarbon potential for countries in the Arctic will be significant – far larger than in the South China Sea. A July 2008 study by the US Geological Survey estimated that total undiscovered, conventional oil and gas resources in the Arctic would include 90bn barrels of oil, 1,669tn cubic feet of natural gas and 44bn barrels of natural gas liquids – all largely offshore.

Control over a number of islands and bodies of water – from the Northwest Passage (claimed by Canada as internal waters) to the Northern Sea Route (claimed by Russia as internal waters), the Beaufort Sea (disputed by Canada and the US), Hans Island (disputed by Denmark and Canada) and the Lomonosov Ridge (disputed by Russia, Denmark and Canada) – is still being negotiated under the aegis of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, which includes the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf.

At a minimum, it looks like the early 21st century will be an era when naval power comes back to the fore.

This is just what the world economy does not need:

If Citigroup is right, Saudi Arabia will cease to be an oil exporter by 2030, far sooner than previously thought.A 150-page report by Heidy Rehman on the Saudi petrochemical industry should be sober reading for those who think that shale oil and gas have solved our global energy crunch....

The basic point – common to other Gulf oil producers – is that Saudi local consumption is rocketing. Residential use makes up 50pc of demand, and over two thirds of that is air-conditioning.

The Saudis also consume 250 litres per head per day of water – the world's third highest (which blows the mind), growing at 9pc a year – and most of this is provided from energy-guzzling desalination plants.

The study predicts that the Kingdom could be a net importer of oil starting as soon as 2030. Needless to say, the consequences of such a move would be profound. Saudi Arabia would not only see its strategic weight plummet, but (more importantly) global energy supplies would be that much tighter.

James Clad and Robert Manning make the case for deft diplomacy in the South China Sea:

Of course, we can keep relying on America's countervailing actions, knowing that China doesn’t play well in a multilateral space. But this game is prone to miscalculations by all sides. Nor does there seem much to gain from spending more time on “confidence building measures” or on a “multilateral security architecture” of regional groupings heavy on acronyms and light on results.To find something new, we might try looking backwards – to a type of split-the-difference US diplomacy last deployed after Russia and Japan had fought a war in 1905. The next year, Theodore Roosevelt brokered a peace that lasted three decades, allowing China, Europe and the US to adjust to Japan’s rise as a major power.

To achieve something similar today would mean finding ways to facilitate commercial exploitation of the South China Sea. Privately, some chief executives of Chinese energy companies have spoken recently of their desire to form offshore joint ventures with western companies. Such joint exploitation could proceed by means of agreements resting expressly on a “without prejudice” basis – where companies, and the states in which they are domiciled, would make clear that mutual oil and gas exploration and production would occur “without prejudice” to their parent country’s sovereign claims. The competing claimant countries could agree among themselves as to which companies might participate in extraction in the areas in dispute.

Who knows if this would work, but it sounds like an idea worth pursuing.

David Ignatius writes that the U.S. is slowly duplicating the strategy it deployed against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan in the 1980s again in Syria today:

What does this historical comparison suggest? On the positive side, the Afghan mujahedeen won their war and eventually ousted the Russian-backed government. (Yes, that's another eerie parallel.) On the negative, this CIA-backed victory opened the way for decades of chaos and jihadist extremism that are still menacing Afghanistan, its neighbors and even the United States.

Ignatius goes on to list some "best practices" so the U.S. can aid Syria's civil war but lower the chances it will incur blow back:

The U.S. should work hard (if secretly) to help the more sensible elements of the Syrian opposition, and limit the influence of extremists. This policy was ignored in Afghanistan, where the U.S. allowed Pakistan (aided by Saudi money) to back the fighters it liked -- who turned out to be among the most extreme and dangerous. America is still trying to undo the mess caused by that exercise in realpolitik. Don't do it again.Finally, the U.S. should subtly play the tribal card, which may be as crucial in Syria as it was in Iraq. The leaders of many Syrian tribes have sworn a blood oath of vengeance against Assad and their power is one reason why the engine of this insurgency is rural, conservative and Sunni. But Iraq showed that the tribal leaders can be the best bulwark against the growth of al-Qaeda and other extremists.

What's scary about Syria is that al-Qaeda is already fighting there, in the hundreds. Cells in Mosul and other parts of northern Iraq are sending fighters across the Syria-Iraq border, with the jihadist pipeline now operating in reverse.

Interesting that none of the lessons Ignatius reaches for include "leave well enough alone." Instead, it's a sophisticated version of "we'll just meddle better this time."

The New York Times explains:

Vladimir V. Putin is the unquestioned supreme leader of Russia, known for his icy stare and steely ways. But now Mr. Putin has taken on a new, perhaps more tender, leadership role. He has guided a flock of birds — through the air.Russia’s president piloted a motorized hang glider over an Arctic wilderness while leading six endangered Siberian cranes toward their winter habitat, as part of an operation called “The Flight of Hope,” his press office confirmed Wednesday.

Our stalled effort in Afghanistan and our unnecessary and expensive effort in Iraq were coupled with a new and bellicose attitude toward friends and foes alike -- the old versus the new Europe; Mission Accomplished; bring it on; and you're either with us or against us. These were the slogans of an unfocused and at times reckless foreign policy.This was the inheritance of President Obama, who also took on an economy in meltdown. When he took office, we were at war in Iraq and Afghanistan. The cost to both our military and our budget could not be sustained. The president committed to ending one war -- Iraq -- and succeeding in the other -- Afghanistan. He kept those promises. By the end of 2011 our troops were home from Iraq, leaving Iraqis in charge of their own future. We are in the process of forming a new relationship of mutual respect and partnership with a new Iraq. - Sen. John Kerry

Is Senator Kerry really suggesting that the U.S. has succeeded in Afghanistan? The only evidence he musters in support of this assertion is that the U.S. has committed to getting out by 2014. That, in and of itself, does not constitute anything.

Back in June, I wrote that:

The only conceivable way an Iran strike would boomerang on Israel in the court of U.S. public opinion would be if the U.S. made some kind of very public ultimatum to Israel which the latter flagrantly ignored, followed by Iranian actions that broadly damaged American interests (terrorist attacks and/or spiking the price of oil).

That may have just happened:

In a move that dismayed Israeli ministers, U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Martin Dempsey, told reporters in Britain last week that the United States did not want to be "complicit" in an Israeli attack on Iran.He also warned that go-it-alone military action risked unraveling an international coalition that has applied progressively stiff sanctions on Iran, which insists that its ambitious nuclear project is purely peaceful.

Dempsey's stark comments made clear to the world that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was isolated and that if he opted for war, he would jeopardize all-important ties with the Jewish state's closest ally.

"Israeli leaders cannot do anything in the face of a very explicit 'no' from the U.S. president. So they are exploring what space they have left to operate," said Giora Eiland, who served as national security adviser from 2003 to 2006.

"Dempsey's announcement changed something. Before, Netanyahu said the United States might not like (an attack), but they will accept it the day after. However, such a public, bold statement meant the situation had to be reassessed."

This may not be enough to stay Israel's hand, but it does appear that the Obama administration has now made the point publicly that a preemptive Israeli attack on Iran over the next few weeks is contrary to U.S. interests. Will it stick?

There's been awful lot of bad economic news of late from all corners of the globe, but I'm here with some good news (kind of). According to a paper from Steve Hanke and Nicholas Krus detailing every global instance of hyper-inflation, there's been no documented case of hyper-inflation being spurred by irresponsible central banks. Felix Salmon breaks it down:

The real value of this paper is its exhaustive nature. By looking down the list you can see what isn’t there — and, strikingly, what you don’t see are any instances of central banks gone mad in otherwise-productive economies. As Cullen Roche says, hyperinflation is caused by many things, such as losing a war, or regime collapse, or a massive drop in domestic production. But one thing is clear: it’s not caused by technocrats going mad or bad.