China's Other Bear Market

There are bull markets. There are bear markets. But in China, there's also a bear bile market. Yum.

« January 2012 | Blog Home Page | March 2012 »

There are bull markets. There are bear markets. But in China, there's also a bear bile market. Yum.

Via Juan Cole.

Israel enjoys a significant lead in almost every category except manpower (not pictured). And, as Cole notes, sheer numbers aren't the whole story, as Israel's equipment is qualitatively far superior to anything Iran would field.

The Iraqi government has released figures stating that 70,000 Iraqis have been killed since 2004, although as AFP reports, that's not the definitive total:

However, the numbers are significantly lower than previous figures that cover a shorter time span, including from Iraq's own human rights ministry.The ministry said in October 2009 that 85,694 people were killed from 2004 to 2008.

And the US military's Central Command posted figures on its website in July 2010 indicating that 76,939 Iraqis, including security forces members, had been killed from January 2004 to August 2008.

Independent British website www.iraqbodycount.org says that at least 114,584 civilians were killed in violence in Iraq from the US-led invasion of 2003 through December 30, 2011.

In a 2003 article for the New York Times, reporter John Burns tried to calculate the number of deaths Saddam Hussein was responsible for:

Doing the arithmetic is an imprecise venture. The largest number of deaths attributable to Mr. Hussein's regime resulted from the war between Iraq and Iran between 1980 and 1988, which was launched by Mr. Hussein. Iraq says its own toll was 500,000, and Iran's reckoning ranges upward of 300,000. Then there are the casualties in the wake of Iraq's 1990 occupation of Kuwait. Iraq's official toll from American bombing in that war is 100,000 — surely a gross exaggeration — but nobody contests that thousands of Iraqi soldiers and civilians were killed in the American campaign to oust Mr. Hussein's forces from Kuwait. In addition, 1,000 Kuwaitis died during the fighting and occupation in their country.Casualties from Iraq's gulag are harder to estimate. Accounts collected by Western human rights groups from Iraqi émigrés and defectors have suggested that the number of those who have "disappeared" into the hands of the secret police, never to be heard from again, could be 200,000.

According to Angus Reid:

People in the Britain, the United States and Canada hold unfavourable views on Iran and believe the country is attempting to develop nuclear weapons, a new Angus Reid Public Opinion poll has found.In the online survey of representative national samples, 70 per cent of Britons, 77 per cent of Americans and 81 per cent of Canadians say they have an unfavourable opinion of Iran.

More than two thirds of respondents in the three countries (Britain 69%, Canada 72%, United States 79%) believe the Government of Iran is attempting to develop nuclear weapons.

When asked about possible courses of action, 30 per cent of Americans, 35 per cent of Canadians and 43 per cent of Britons say they would prefer to engage in direct diplomatic negotiations with Iran. One-in-four Canadians and Americans (25% each)—and one-in-five Britons (20%)—would impose economic sanctions against Iran.

The option of launching military strikes to destroy Iran’s nuclear facilities is endorsed by 15 per cent of Americans, 11 per cent of Canadians and six per cent of Britons. A full-scale invasion of Iran to remove the current government is supported by 10 per cent of Canadians, six per cent of Americans and five per cent of Britons.

In the U.S., the only politically acceptable discussion regarding taxes is generally how deep they should be cut. In France, not so much:

The Socialist tipped to become France's next president took aim at the wealthy Tuesday with plans to slap a 75 percent tax rate on top earners.Francois Hollande said it was simply a case of "patriotism to accept to pay extra tax to get the country back on its feet again" and reverse the policies of President Nicolas Sarkozy that he said favoured the rich.

Rob Goodier tries to find out:

All this undersea treasure hunting got us wondering: Just how much money is out there buried at sea? We put the question to marine archeologists, a historian, and a shipwreck hunter. Their answers ranged from "Who knows?" to "$60 billion"—and each was instructive.An estimate of the value of sunken treasure in the world begins with a guess at the number of sunken ships. James Delgado, director of the Maritime Heritage Program at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), estimates that there are a million shipwrecks underwater now.

President Obama's Google Plus account is making news:

Chinese Internet users taking advantage of temporary access to Google's social networking site, Google+, have flooded U.S. President Barack Obama's page on the site with calls for greater freedom in the world's most populous country."Oppose censorship, oppose the Great Firewall of China!" one user posted, one of hundreds of comments in Chinese or by people with Chinese names that dominated the site over the weekend.

Beijing's blocking of websites and censoring of search results for politically sensitive terms is known colloquially as the "Great Firewall of China." With sites such as Facebook and Twitter blocked, self-censoring homegrown equivalents like Sina Corp's microblogging platform, Weibo, fill the void.

It was unclear why Google+ was accessible for some users in China for part of the past week. A Google spokesman said the company had not done anything differently that would have led to the access. One Google executive told Reuters that the company had noticed the opening early last week.

The U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan sent a top-secret cable to Washington last month warning that the persistence of enemy havens in Pakistan was placing the success of the U.S. strategy in Afghanistan in jeopardy, U.S. officials said.The cable, written by Ryan C. Crocker, amounted to an admission that years of U.S. efforts to curtail insurgent activity in Pakistan by the lethal Haqqani network, a key Taliban ally, were failing. Because of the intended secrecy of that message, Crocker sent it through CIA channels rather than the usual State Department ones. - Washington Post

It's understandable why Washington wants Pakistan to end its support for the Haqqani network, but it's impossible to understand why we've based our Afghan strategy around the idea that this support is actually going to disappear and Afghanistan will be "stabilized" according to our prerogatives. It's been obvious for years now that Pakistan is looking out for its own interests in Afghanistan irrespective of American threats or inducements. Yet 10 years later, here is America's ambassador saying that all of our efforts will go to pot unless Pakistan does something it has repeatedly made clear it would not do.

Bernard Finel is equally exasperated:

See, our approach to both those countries has been posited on the believe that they are somehow acting contrary to their own interests and that if we just educate them they’ll come around. What do I mean?Well, we escalated in Afghanistan on the assumption that it would be in Pakistan’s interest to suppress radical groups across the border. Why? Because they are “obviously” a threat to Pakistan. But look, the Pakistanis are not stupid. They get that there is a double-edged sword dynamic here, but they have made a conscious choice to use radical groups as a proxy both to maintain influence in Afghanistan and as a hedge against India. They have a redline, apparently, about the expansion of those groups into Pakistan proper — at least into the provinces beyond the FATA — but otherwise, they have zero interest in supporting the eradication of groups like the Haqqani network. But instead of understanding this definition of their interests, we continue to act as if they are operating under some sort of false consciousness that we can alter simply by, you know, explaining their own interests to them.

Myra MacDonald makes another critique:

Meanwhile, the U.S. strategy is, and has always been, internally inconsistent. At one level it wants to retain military bases in Afghanistan after 2014, which could be used for drone strikes and other military operations against Pakistan where many of the Islamist militants are based. Yet it needs Pakistani endorsement for a deal with Taliban leader Mullah Mohammed Omar, whose support is required to bring the rest of the movement on board and who is, despite Pakistani official denials, believed to be living in an Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) safe house, most likely in Karachi.In short, however inconsistent the strategy, it has depended on bluff. And that bluff is weakening.

I am increasingly reminded of the words of one western official speaking last year on Afghanistan: ”We stay we lose, we leave we lose.”

I think it's this zero-sum thinking that has gotten us into trouble in the first place. America can't "lose" in Afghanistan. We've killed bin Laden and shredded most of the senior leadership that perpetrated 9/11. Why is this not enough?

It's not clear at this point whether President Obama's strategy will deprive Iran of a nuclear weapon, but it might deliver the U.S. into the grips of another recession.

Put simply, if oil remains as expensive as it currently is, or gets even higher, the U.S. economy will almost certainly fall back into a recession - potentially a nasty one given the already high unemployment.

Now, there are a lot of structural factors beyond the Iran standoff that are driving expensive oil, particularly the growth in demand from Asia. Even if the U.S. were to ease Iranian supply back into the market, oil is likely to be expensive on an ongoing basis (unless we tip back into a recession again). But we're not going to do that. In fact, U.S. strategy right now is to keep as much Iranian oil off the market as possible, making the price higher.

Now, supporters of this strategy claim that Saudi Arabia stood ready to make up for the loss of Iranian crude - but that's not happening. Not because Saudi Arabia doesn't want to pump more, it's because they can't pump more.

Presumably the administration believes that an Iran with nuclear weapons would do worse damage to U.S. interests than a possible second recession (or a prolongation of the Great Recession bequeathed by the Bush administration). Unfortunately, we may be about to test this hypothesis.

Some of them just aren't safe abroad.

David Makovsky explains how President Obama and Prime Minister Netanyahu can improve their relationship:

How can Obama and Netanyahu win each other's trust? The two sides should come to a more precise understanding of U.S. thresholds for the Iranian nuclear program and American responses should they be breached, as well as an agreement on a timetable for giving up on sanctions so their Iran clocks are synchronized. In other words, the two sides need to agree on red lines that might trigger action. Israel will probably seek some guarantees from the United States before agreeing to forgo a pre-emptive strike that might not succeed.It may turn out that such guarantees are impossible, given the mistrust between the two parties and the ever-changing regional circumstances. Whatever the mechanism, there is no doubt that the U.S.-Israel relationship could benefit greatly from a common approach toward the Iran nuclear program at this tumultuous time.

I don't think such guarentees would break down over issues of trust but over issues of threat perception. Ultimately, it's impossible to form a "common approach" when the strategic interests are divergent - as they are in this case. Up to a point, both the U.S. and Israel want Iran to abandon their pursuit of nuclear weapons capability but it's clear that the Israelis feel this way because they believe Iran would pose an existential threat to their security, while the U.S. feels this way because it wants to prevent a regional arms race and blunt any Iranian bid for hegemony. If what senior military and intelligence officials in the U.S. say about Iran is true, then it's clear there's a limit to how far we're willing to go with Iran. Israel, I suspect, has no real limit because it feels the stakes are higher.

Ultimately, the U.S. and Israel can't synchronize their positions because they're different positions - not because Netanyahu and Obama can't get along.

In listing the reasons why the Iran debate is playing out a bit differently than the Iraq war debate, it's also important to highlight the role Israel plays. Via the New York Times:

Another critical difference from the prewar discussion in 2003 is the central role of Israel, which views the possibility of an Iranian nuclear weapon as a threat to its very existence and has warned that Iran’s nuclear facilities may soon be buried too deep for foreign bombers to reach.Israel’s stance has played out politically in the United States. With the notable exception of Representative Ron Paul of Texas, Republican presidential candidates have kept up a competition in threatening Iran and portraying themselves as protectors of Israel. A bipartisan group of senators on Tuesday released a letter to President Obama saying that new talks could prove a “dangerous distraction,” allowing Iran to buy time to move closer to developing a weapon.

During the run-up to the Iraq war, the U.S. was in the driver's seat regarding policy. If President Bush had had a change of heart, there would have been no invasion. That's not the case with Iran. Israel is (I think) likely to trigger its own war against Iran if the U.S. declines to start one. That war may go well as far as the U.S. is concerned - with little anti-American fallout or retaliatory strikes. Or it may go disastrously - with the U.S. being targeted or called in to re-open the Strait of Hormuz.

But either way, the U.S. simply doesn't have the initiative with respect to Iran as it did with Iraq. This is another reason why advocates of attacking Iran - despite being wrong about the costs and consequences of the Iraq war - are still dominating the public debate. If a war, in some fashion, is inevitable, it makes more sense (in their view) that the U.S. wage it and lead it than get dragged into it after the fact.

Shadi Hamid makes the case for military intervention in Syria:

Military action, in any context, should not be taken lightly. But neither should standing by and proposing measures that have, in Syria, so far failed to work. Opponents of intervention need to explain how staying the current course—hoping that diplomacy might work when it has not for nearly a year—is likely to resolve an increasingly deadly civil war.

He then goes out to outline what he thinks would resolve the civil war - creating "safe zones" inside Syria and arming the rebels. This seems to me unlike to "resolve" the war so much as escalate it, but that aside I think a more fundamental question needs to be answered: why is it anyone's responsibility to end the Syrian civil war?

Peter Beinert has a question:

How can it be, less than a decade after the U.S. invaded Iraq, that the Iran debate is breaking down along largely the same lines, and the people who were manifestly, painfully wrong about that war are driving the debate this time as well?

I'll take a stab at this. First, among the people who were "manifestly, painfully wrong" about Iraq are the current U.S. secretary of state and the vice president. Support for the Iraq war was a largely bi-partisan affair at the time it was launched, and so very few people have an incentive to insist on accountability for that advocacy.

The second reason is that there's always a bias toward activism when it comes to the Washington debate. It would be unheard of for President Obama to stand at a podium, shrug his shoulders and tell the American people that the U.S. will not go to war against Iran because the country poses almost no threat to the United States. Instead, he must defend his program of sanctioning and isolating Iran while insisting that "all options are on the table."

Finally, and most importantly, the situations are just very different. To sell the Iraq war, the Bush administration had to engage in a lot of threat inflation and dubious assertions about Iraqi capabilities and intentions. With Iran, that's not (as much) the case. We know they have a nuclear program and whether they divert it to military uses or not, they are significantly further along the path toward a bomb than Iraq ever was. Ditto with terrorism. There is a much stronger link between Iran and Hezbollah than there ever was between Iraq and al-Qaeda (although thanks to the war, al-Qaeda is now ensconced in Iraq).

Nicholas Burns is unhappy that India is not doing what it's told acting irresponsibly by not agreeing to embargo Iranian oil:

There’s a larger point here about India’s role in the world. For all the talk about India rising to become a global power, its government doesn’t always act like one. It is all too often focused on its own region but not much beyond it. And, it very seldom provides the kind of concrete leadership on tough issues that is necessary for the smooth functioning of the international system.

I imagine if I were an Indian official, I'd be a bit peeved to learn that acting "responsibly" means privileging the interests of the United States over my own country. Nevertheless, Burns has a point. After all, India may rely on Iran for 12 percent of its oil imports, but look at what the United States has been willing to do for India:

Presidents Obama and Bush have met India more than halfway in offering concrete and highly visible commitments on issues India cares about. On his state visit to India in November 2010, for example, President Obama committed the U.S. for the very first time to support India’s candidacy for permanent membership on the U.N. Security Council.

I don't know about you, but if the U.S. was asked to forgo 12 percent of its oil imports in exchange for another country's endorsement for a seat on a multilateral forum, I'd make the trade. I mean, c'mon, 12 percent? The U.S. gets about that much from the Persian Gulf - and we barely pay that area any attention at all...

And look, Burns is making a very solid point. If India wants a good relationship with the United States, they shouldn't do business with America's enemies. After all, the U.S. has certainly held itself to that standard with India's enemies. Right?

In sum, the contrast between the U.S. administration’s unwillingness to act in our best interest and the despotic regimes could not be more clear. This is how we lose influence — through lack of will, self-delusion and aversion to conflict. And when we do, other powers take our place, shifting the landscape against human rights, against democracy and against the West.Contrast this with the preferred approach of Mitt Romney, who told me last week: “Where you have someone who is a brutal tyrant killing his people you call him out immediately. You support openly and aggressively the people [opposing him].” In other words, we lead and forestall other powers from gaining the upper hand in the region. - Jennifer Rubin

Indeed. And if some of the people opposing the brutal tyrant happen to be members of al-Qaeda well, at least we're leading!

Is real. You've been warned.

Defense Secretary Leon Panetta said Thursday that U.S. intelligence shows Iran is enriching uranium in a disputed nuclear program but that Tehran has not made a decision on whether to proceed with development of an atomic bomb. - Associated Press

Director of National Intelligence James Clapper said the same thing recently - there is no indication yet that Iran's leaders have decided to go all the way toward a nuclear weapon. Now, U.S. intelligence could be wrong. But if they're not, this also highlights one of the risks of any Iran attack: after Iran rebuilds, which they would, they may no longer be satisfied with getting to the nuclear threshold. An attack would buy time but could also, perversely, encourage the very thing it is attempting to discourage.

We're seeing a similar dynamic with respect to Iran's global terrorism today. It's no coincidence that the Iranians are increasing international attacks against Israeli interests in response to increased pressure and attacks inside Iran. The very behavior we claim to find so troubling about the Iranian regime is getting objectively worse as a result of a policy of pressure and isolation - not improving.

Now it's early still, and perhaps the regime is lashing out now but will meekly slink back as the weeks progress. This could be a "last throes" kind of thing. Patience is needed. But at a certain point in time the results have to speak for themselves. If the goal of policy is to reduce the "threat" from Iran, the incidence of Iran behaving in a threatening manner has to actually decrease.

Gallup has updated their list of countries Americans view favorably:

Adam Segal argues that the popular perception of China as a cyber superpower is overwraught:

Two recent studies of national cyber power have placed China near the bottom of the table. China is number 13 on the EUI-Booz Allen Hamilton Cyber Power Index, behind Argentina, Mexico, and Brazil but better off than Russia, Turkey, South Africa, and India (the United Kingdom, United States, and Australia are the top three). The Brussels-based Security & Defence Agenda groups China with Italy, Russia, and Poland in the fifth tier (the U.S. and the UK are in the third tier, below Finland, Sweden, and Israel; the top group is empty).These are very subjective studies based on interviews, surveys, and vague metrics. Still, they cut against the grain of popular perceptions. If you were just paying attention to the almost weekly reporting in the Western press about alleged Chinese cyber espionage, you could be forgiven for thinking that China ruled the cyber waves. Yet recent writings in the Chinese press have more of a “China is vulnerable” flavor and suggest that analysts, if not characterizing the country’s cyber strategy as weak, think there is a great deal of work that remains to be done.

A nation that represses its own people cannot ultimately be a trusted partner in an international system based on economic and political freedom. While it is obvious that any lasting democratic reform in China cannot be imposed from the outside, it is equally obvious that the Chinese people currently do not yet enjoy the requisite civil and political rights to turn internal dissent into effective reform.I will never flinch from ensuring that our country is secure. And security in the Pacific means a world in which our economic and military power is second to none. It also means a world in which American values—the values of liberty and opportunity—continue to prevail over those of oppression and authoritarianism. - Mitt Romney

So American values can't be imposed on China, but we mustn't let that realization get in the way of brow beating them about all their internal failings anyway and surrounding them with U.S. military power.

And then President Romney will ask the Chinese - pretty please - to borrow their money.

The United States and Iran have been on a collision course since the Iranian revolution in 1979, when elements of the newly proclaimed Islamic Republic took U.S. diplomats and Tehran embassy personnel hostage. U.S. relations with Iran have been bad ever since. - Tod Lindberg

Right. Pay absolutely no attention to U.S.-Iranian relations before 1979, since nothing says "good relations" like fomenting coups.

A new Pew poll has found that most Americans would support taking military action against Iran:

The public supports tough measures – including the possible use of military force – to prevent Iran from developing nuclear weapons. Nearly six-in-ten (58%) say it is more important to prevent Iran from developing nuclear weapons, even if it means taking military action. Just 30% say it is more important to avoid a military conflict with Iran, even if it means that country develops nuclear weapons. These opinions are little changed from October 2009.

However, the U.S. is not as supportive when it comes to helping Israel should they attack:

About half of Americans (51%) say the United States should remain neutral if Israel takes action to stop Iran’s nuclear program, but far more say the U.S. should support (39%) than oppose (5%) an Israeli attack.

Thomas P.M. Barnett sees a war against Iran as inevitable:

While the debate over whether Israel will strike Iran ebbs and flows on an almost weekly basis now, a larger collision-course trajectory is undeniably emerging. To put it most succinctly, Iran won't back down, while Israel won't back off, and America will back up its two regional allies -- Israel and Saudi Arabia -- when the shooting finally starts. There are no other credible paths in sight: There will be no diplomatic miracles, and Iran will not be permitted to achieve a genuine nuclear deterrence. But let us also be clear about what this coming war will ultimately target: regime change in Tehran, because that is the only plausible solution.While I don't know if Israel and the U.S. will reach as far as an attempted regime change, I think Israeli air strikes are almost certainly coming.

Daniel Byman argues that any intervention in Syria should actually accomplish something useful:

To be of any value, an intervention must end the bloodshed, or at least diminish it dramatically. Syria also must remain an intact state capable of policing its borders, stopping terrorism and providing services to its people. It should not fragment into a failed state, trade Assad for another dictator or become a pawn of foreign powers such as Iran.

Bernard Finel isn't convinced:

Byman’s argument is, essentially, if you can’t fix it completely and forever, then you shouldn’t do anything. I think this is precisely wrong. Byman’s argument is exactly the sort of logic that got us a massive escalation in Afghanistan. If you insist that any use of the military must achieve maximalist goals, then you inevitably end up with recommendations for massive interventions, state-building, and the like.Instead, we need to be thinking about limited objectives and limited means. There are three reasons:

(1) While raising the bar on intervention may seem cautious, it really isn’t. It forces policy discussions into an all-or-nothing logic, when in the final analysis neither one is acceptable. The more we talk about massive intervention as the only option, the more likely that becomes because as the violence continues in Syria, pressure to “do something” will mount. Some people argue “all or nothing” because they think “all” is too much and so won’t happen, and the result will be “nothing.” That is a dangerous game.

I've been critical of the maximalist goals set in Afghanistan and I think there is something to Finel's analysis here. One immediate problem, however, is how the U.S. will justify an intervention. I think it's very difficult to argue - as Finel does - that a "limited" intervention is acceptable if the stated goal of U.S. policy is the protection of Syrian lives. That's because it's not remotely clear that arming Syrian rebels or bombing Syrian tanks will result, over the medium term, in fewer Syrians being killed. It's not a "maximalist" argument to say that an intervention staged on the grounds of saving human life should actually result in the saving of human lives.

You can argue for a limited intervention, however, on realpolitik grounds. It would go something like this: we don't particularly like the Syrian regime and think that toppling it, or tying it down in a bloody insurgency, would advance U.S. interests in isolating Iran. Therefore, irrespective of the harm done to the Syrian people, we will intervene to give the rebels a fighting chance.

There are problems with this course of action as well - particularly in creating an Afghanistan redux, where the forces we empower turn around and make big problems for us several years down the road. For instance, should we be encouraged that guns are flowing into Syria from Sunni strongholds in Iraq that were home to al-Qaeda in Iraq? There is something of a blase attitude about this in much of the "do something" talk about Syria, but it's worth thinking about.

(AP Photo)

Gideon Rachman thinks some do:

My impression from talking to policymakers in Berlin recently, and following the debate subsequently, is that different bits of the German government have different views on the matter. The Foreign Ministry and people around the chancellor seem keen to keep the Greeks in – for a mixture of political and economic reasons. The Finance Ministry is much more equivocal. The formula I heard repeated a fair amount in Berlin was that “it is upto the Greeks to decide whether they want to stay in.” This struck me as a less than ringing endorsement. A few months ago, you would have heard people saying that it was unthinkable for Greece to leave. Now, it’s clearly thinkable.

Stan Grant says the era of "cheap China" is over:

The Chinese factory floor ain't what it used to be. Heavy industry machines now sit idle, where once hundreds of workers would have crammed into Dickensian sweat shops, slaving away for little pay.China's army of migrant workers are smarter than ever, demanding higher pay and better conditions, armed with tough government labor laws.

Ever since it was reported that Israel was sponsoring terrorist attacks against Iranians, we've seen a rather curious turn of affairs: supporters of Israel have come to the defense of terrorism.

Daniel Larison picks up the thread, arguing that the moral approbrium due terrorism should hold no matter what:

Tobin makes the charge that the other critics and I are indulging in such moral relativism for the purpose of “delegitimizing” Israel, but it is Tobin who wants one standard for judging Israeli behavior and a very different one for judging Iranian behavior. What all of us are saying is that there is a moral and legal equivalence between different acts of terrorism, and that the victims of terrorist attacks are equally human. The lives of Iranian civilians have just as much value as the lives of Israeli civilians. The former don’t become more expendable because their government is authoritarian, abusive, and supports Hamas. If it is wrong and illegal for one group or state to commit acts of terrorism, it must be wrong and illegal in all cases. The reasons for the acts shouldn’t matter, and neither should the justifications. Either we reject the amoral logic that the ends justify the means, or we endorse it.

Jonathin Tobin followed up saying:

Above all, what Greenwald, Wright and Larison have a problem with is the entire idea of drawing a moral distinction between Iran and Israel. That is why their entire approach to the question of the legality of Israel’s attacks is morally bankrupt. Underneath their preening about the use of terrorists, what Greenwald, Wright and Larison are aiming at is the delegitimization of the right of Israel — or any democratic state threatened by Islamist terrorists and their state sponsors — to defend itself.

Michael Rubin also weighed in:

Jonathan Tobin is absolutely right to dismiss those who argue that Israel forfeited its moral standing by allegedly assassinating Iranian nuclear scientists. Rather, the fact that some argue Israel “started it” shows moral blindness and ignorance of context.

The "context" in question appears to be the fact of who is committing the terrorism. When Iran does it, according to Rubin, it's bad. When Israel does it, it's necessary.

Ultimately, the question seems to boil down to whether a state is justified in committing terrorism if it believes the stakes are high enough. By sanctioning Israel's use of terrorism, Israel's supporters are decrying a "moral equivalency" between Israel and her enemies while simultaneously endorsing moral relativism: they imply that any moral judgments about terrorism must begin with an assessment of the state or group employing it.

Personally, I tend to agree with Larison that this is indeed "amoral logic" but I don't necessarily think that Tobin and Rubin are wrong, at least as far as the general principle goes. I don't agree with the Tobin/Rubin argument that the stakes in this specific case are "existential," but I do believe that if the stakes were existential then it's difficult to rule out any tactic, however awful. Indeed, the very bedrock of a "realist" foreign policy seems to hinge on the notion that states must prioritize the lives of their own citizens above the lives of others. That's ugly, no doubt, and I think there's an argument to be made that the U.S. should often behave as if this were not the case (and build a normative atmosphere that rejects, when possible, amoralism). But at the end of the day, there's a limit to how far that project can go.

Update: Rubin takes issue with my characterization of his post:

But that was not the point of the post Sclobete [sic] selectively cites, nor is it even a fair reading of it. Rather, I list a litany of anti-Israel and anti-Jewish terrorism sponsored by Iran during the past two decades and exclaim that pundits who are jumping on the terrorism bandwagon now show their selectivity by having ignored for so long Iranian sponsorship of terrorism against Israel, Israelis, and Jews.As for assassination, a tactic used to prevent a wider conflict or an existential challenge, I see nothing wrong with it nor, for that matter, does the Obama administration. Assassination does not violate international law; it is not terrorism.

The broader problem, however, is that there is simply no universally accepted definition of terrorism. As I noted in this paper on asymmetric threat concept, as of 1988 there were more than 100 definitions of terrorism in use in Western countries, and that number has only proliferated in the past quarter century.

I can state unequivocally that Rubin is wrong about one thing: the spelling of my last name. Beyond that, I don't know if this is as exculpatory as Rubin thinks - saying another side "started it" or that it's all too rhetorically vague to pass judgment on doesn't suddenly absolve the behavior in question.

I'm not a legal expert on these matters, but I believe the position of the U.S. government since President Ford is that assassination is illegal. When then-U.S. ambassador to Israel Martin Indyk was asked his position on Israel's policy of assassinations, he said:

“The United States government is very clearly on the record as against targeted assassinations. They are extrajudicial killings, and we do not support that.”

Like Iraq and Afghanistan before it, analysts say, Syria is likely to become the training ground for a new era of international conflict, and jihadists are already signing up. This weekend, Al Qaeda’s ideological leadership and, more troublingly, the more mainstream Jordanian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood, called for jihadists around the world to fight Mr. Assad’s government....Tribal leaders and security officials describe a small but increasing flow of weapons to Syria from Anbar Province and areas around Mosul, the northern city that is a headquarters for Al Qaeda in Iraq. For some weapons smugglers the price of an automatic rifle has increased dramatically — to $2,000 from about $300, according to one account. [Emphasis mine] - New York Times

It's certainly encouraging to see Iraq serve as a model for the region.

Leslie Gelb does a nice job framing a question that's been on my mind amidst repeated calls for Western military intervention in Syria:

Faced with evil, Americans always want to be on the side of the angels. So American interventionists, hawks, and human-rights types are banding together, as they did in Libya, to stop President Bashar al-Assad from killing his people. But when interventionists become avenging angels, they blind themselves and the nation, and run dangerously amok. They plunge in with no plans, with half-baked plans, with demands to supply arms to rebels they know nothing about, with ideas for no-fly zones and bombing. Their good intentions could pave the road to hell for Syrians—preserving lives today, but sacrificing many more later.[Emphasis mine]This is an important point that was overlooked in Libya and will probably be overlooked again with respect to Syria: what constitutes protecting people? If you spare 10,000 civilians in a Benghazi or Homs only to set in motion a series of events that winds up killing and displacing as many if not more people over a five or ten year period, have you actually done anything that's morally commendable? Do lives become less important if they're lost gradually instead of in one mass slaughter?

We have been told that the intervention in Libya was a vindication of the Responsibility to Protect - the doctrine that legitimizes military intervention against a state committing atrocities against its own people - but how can we render any moral judgment on what's occurred in Libya? It's not at all clear that the country can be responsibly governed and continued tribal in-fighting could claim as many lives - or more - than any Gaddafi crackdown.

It often looks like advocates of "Responsibility to Protect" want a pass on this, using the overwhelming humanitarian emergency to overwhelm (or brow-beat) those asking for restraint without tackling the broader issue of how their proposed remedy will save lives over the long term. But it won't go away. If the U.S. steps into Syria and starts arming factions and, perhaps, carving out safe havens and humanitarian enclaves with no-fly-zones it could set Syria up for a protracted civil war. If that civil war claims more lives than those lost to date in Assad's brutal crackdown, can we really be said to be "protecting" anyone?

(AP Photo)

If the deprivation of rights is indeed the root cause of terrorism, why did all these people pursue their cause without resorting to terror? Put simply, because they were democrats, not terrorists. They believed in the sanctity of each human life, were committed to the ideals of liberty, and championed the values of democracy.But those who practice terrorism do not believe in these things. In fact, they believe in the very opposite. For them, the cause they espouse is so all-encompassing, so total, that it justifies anything. It allows them to break any law, discard any moral code and trample all human rights in the dust. In their eyes, it permits them to indiscriminately murder and maim innocent men and women, and lets them blow up a bus full of children. - Benjamin Netanyahu

Israel is, after all, locked in a conflict with an Iranian regime that has made no bones about its intentions. Just last week, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei repeated the standard Iranian line about Israel being a “cancerous tumor” that must be eradicated. Coming from a man who leads a regime based on religious fanaticism and which is dedicating massive amounts of the country’s resources towards achieving its nuclear ambitions, this is no idle threat. Under these circumstances, Israel is entirely justified in using whatever means it has to prevent Khameini’s government from achieving its genocidal ends. The MEK may be an unattractive ally, but with its Iranian members and infrastructure of support inside the country, it is an ideal weapon to use against the ayatollahs. - Jonathan Tobin

Several people have jumped on Tobin for saying this, but I think he's actually making a point that many critics of neoconservatism (particularly post 9/11 neoconservatism) have been saying since the "war on terror" began: terrorism is a tactic, not an ideology. Tobin approves of terrorism when it's being used by Israel against Iran and disapproves of it when it's used by Palestinians against Israel. But Tobin is acknowledging that - contrary to Benjamin Netanyahu's insistence - terrorism itself is not an outgrowth of a "totalitarian" mindset but a tactical weapon to use against an adversary when other tools are unavailable or too risky.

Syria will have a post-Assad future. That future could be in the hands of Qatari backed Salafis, Saudi-backed Islamists, or the Western world could have a say. Sitting on the sidelines will ensure that we have as little as possible. - Danielle Pletka

I think this is a good way of putting it, but it also raises an important question. Let's suppose the Western world has its say - would it be loud and decisive enough to marginalize the Qatari-backed Salafis or the Saudi-backed Islamists? Isn't it reasonable to conclude that there is a larger constituency inside Syria for what Qatar and Saudi Arabia are peddling than what the U.S. would offer? The unfolding events in Egypt would make me very leery about basing any U.S. strategy on the presumption that there is a broad constituency in any Middle Eastern country that would be keen to take its cue from the U.S. or Western powers.

I'm not sure how the U.S. should proceed with respect to the uprising in Syria, but I think the claim, on the basis of no evidence whatsoever, that those battling the Assad regime are democrats needs to be subjected to scrutiny. (See this, for example, which equates American reluctance to overthrow Assad with a reluctance to promote democracy, as if the two things are in anyway related.)

There is absolutely no reason to believe that Syria's rebel forces will be any less brutal than the regime they are seeking to overthrow. There is no way to know how they will govern (and there is obviously no reason to trust declarations made explicitly to court foreign assistance). Nor is there any way U.S. or NATO assistance can ensure a democratic outcome. The U.S. couldn't steer Iraqi politics to its liking while it was an occupying power - it would have even less leverage in a post-Assad Syria.

None of this is to say that a democratic Syria is impossible or that those risking their lives against the Assad regime do not genuinely desire a more representative government. It's also not to suggest that there are no good reasons to intervene (in some fashion) in Syria's uprising. But for the case to be made with a modicum of intellectual honesty, it has to acknowledge that the nature of a post-Assad regime is absolutely unknowable and could produce human carnage far in excess of anything we're currently witnessing.

Dan Trombly thinks it's possible:

Given that rapidly overthrowing Assad without major overt military action from a broad coalition of forces is a pipe dream anyway, the United States should consider contingency plans in which it works through, rather than against, the specter of protracted civil war. To be able to bleed Iran in Syria would, relative to the risks involved, be a far more significant strategic opportunity against Iranian power relative to the investment and risk than would be a major overt campaign to overthrow Assad outright. The more blood and treasure Iran loses in Syria – even if Assad stays in power longer – the weaker Iran will be.

Not the people's business:

Three Indian politicians from a morally conservative party, including a women's affairs minister, resigned on Wednesday after being caught watching pornography on a mobile phone during a session of state parliament.News channels broadcast footage showing Karnataka state Minister for Cooperation Laxman Savadi sharing a porn clip with his colleague C.C. Patil, the minister for women and child development, while sitting in the state assembly.

The Japan Times charts it:

The estimate shows that Japan's population will shrink by around 30 percent to 86.74 million by 2060, and that the percentage of people aged 65 or older will increase from 23.0 percent in 2010 to 39.9 percent in 2060. People will also live longer than now. The average life expectancy will rise from 85.93 years in 2011 to 90.93 years in 2060 for women and from 79.27 years to 84.19 years for men during the same period. Nursing care and medical services will become increasingly important. The government should show clearly the costs and benefits of such services so that people will be better prepared to accept the burden of higher social welfare costs.

Hamish McRae says the consequences would be enormous:

Note that Angela Merkel has openly supported Nicolas Sarkozy in the forthcoming elections. Leaving aside the fact that such an endorsement may have unintended consequences, the motive and timing are interesting. Mr Sarkozy's principal rival for the presidency, François Hollande, has promised a reversal of the Sarkozy austerity measures, including bringing the retirement age back to 60 (from 62) and creating more than 200,000 state or state-funded jobs.In short, it is perfectly plausible that France's next president will follow policies that are exactly the reverse of those now being urged on all the weaker eurozone states. Think of the consequences. A huge intellectual and practical rift would open up between Germany and France and the entire eurozone austerity programme would be undermined, maybe destroyed. Greece has to be screwed down now not just because of the financial deadline of bonds it cannot repay, but also because of the political deadline of the French elections.

A new ABC News/Washington Post poll gives President Obama high marks in foreign policy:

Eighty-three percent of Americans in the latest ABC News/Washington Post poll approve of Obama’s use of unmanned drones against terrorist suspects, 78 percent back the drawdown of U.S. troops in Afghanistan and 70 percent favor keeping open the Guantanamo Bay detention center – the latter a reversal by Obama of his 2008 campaign position.

It also notes American comfort with targeting fellow citizens for death by drone:

Two-thirds in this poll, produced for ABC by Langer Research Associates, also favor the use of unmanned drones specifically against American citizens in other countries who are terrorist suspects – potentially touchier legal territory.Interesting to note that the poll specifically describes those targeted by drones as "suspects" - so there appears to be ample support for killing Americans even if their guilt is not firmly established.

According to Angus Reid, the French and Greeks don't rank so highly in British esteem:

In the online survey of a representative sample of 2,011 British adults, about a third of respondents say they have an unfavourable opinion of France (35%) and Greece (32%).The difference between the proportion of favourable and unfavourable opinions for both Greece and France is only ten points. Half of Britons (49%) have a favourable view of Germany, while one-in-four (25%) disagree.

At least half of respondents hold favourable opinions of all of the other nations included in this survey, such as Luxembourg (53%), Portugal (55%), Italy (57%) and Belgium (also 57%). The highest ranked EEC members are Spain (63%), Ireland (67%), Denmark (also 67%) and the Netherlands (69%).

Stephen Roach thinks so:

Yet fears of hard landings for both economies are overblown, especially regarding China. Yes, China is paying a price for aggressive economic stimulus undertaken in the depths of the subprime crisis. The banking system funded the bulk of the additional spending, and thus is exposed to any deterioration in credit quality that may have arisen from such efforts. There are also concerns about frothy property markets and mounting inflation.While none of these problems should be minimized, they are unlikely to trigger a hard landing. Long fixated on stability, Chinese policymakers have been quick to take preemptive action....

India is more problematic. As the only economy in Asia with a current-account deficit, its external funding problems can hardly be taken lightly. Like China, India’s economic-growth momentum is ebbing. But unlike China, the downshift is more pronounced – GDP growth fell through the 7% threshold in the third calendar-year quarter of 2011, and annual industrial output actually fell by 5.1% in October.

But the real problem is that, in contrast to China, Indian authorities have far less policy leeway. For starters, the rupee is in near free-fall. That means that the Reserve Bank of India – which has hiked its benchmark policy rate 13 times since the start of 2010 to deal with a still-serious inflation problem – can ill afford to ease monetary policy. Moreover, an outsize consolidated government budget deficit of around 9% of GDP limits India’s fiscal-policy discretion.

A new survey from Gallup shows that a broad majority of Egyptians do not want American economic aid.

If this NGO crisis continues they may get their wish.

Mario Loyola wants international law to enshrine a doctrine of preventative war:

The right of early preemption against threats like Iran’s nuclear program must become an international norm of general acceptance if preemptive threats are to have any deterrent value. Current norms — and the diplomatic strategies derived from them — have only incentivized Iran to sprint toward nuclear weapons. The strategy of increasingly onerous sanctions may be painful for Iran, but it implies that military strikes are off the table as long as further sanctions are in prospect. Thus, starting with the first Security Council sanctions in 2006, Iran knew that it had several risk-free years ahead of it to develop WMD.The only principle that can justify early preemption against a WMD threat is one that calls on dangerous regimes to be transparent in their dispositions. What you could call “regime transparency” is the key. This is the cardinal principle that was all along missing in the Bush administration’s justification for war against Iraq. The burden of proof should have been on Saddam to demonstrate the non-threatening nature of his weapons programs. In the long run, such a burden could be met only by a regime that was itself essentially transparent, in which the business of government was conducted in an orderly and law-abiding way.

I don't see how this is a practical or desirable standard. Enshrining the doctrine of preventative war around inherently subjective and conditional terms such as "dangerous" or "non-transparent regimes" seems to open the door to all kinds of questions: dangerous to whom? How dangerous? What constitutes a lack of transparency? And so on. What, in other words, stops Russia from claiming the right to attack Georgia preemptively if it purchases U.S. military equipment? What is the normative case against China attacking Taiwan or Iran attacking Saudi Arabia if these states increase their lethality through U.S. arms purchases?

Obviously, you can embrace a policy that states that only the United States has the prerogative to attack other countries on a preemptive basis, but I highly doubt many countries would be interested in enshrining that as "international" law.

Loyola bases his argument on the existence of nuclear weapons:

The “general principle” for preemptive self-defense is that you can preempt an “imminent attack” but nothing more. That rule is ridiculous, and will sooner or later prove suicidal. Because of the instantly deliverable nature of nuclear weapons, waiting for firm intelligence of an imminent threat is a reckless game of chicken in which the claimed right of preemption is triggered only when it is almost too late to make any difference.

But what's new here? Nuclear weapons have been "instantly deliverable" for many decades now. The U.S. has been able to deal with this unfortunate reality rather well, as the record of nuclear wars and nuclear attacks since 1946 seems to suggest.

That's the headline from the latest Rasmussen poll:

The latest Rasmussen Reports national telephone survey of Likely U.S. Voters shows that 83% believe it is at least somewhat likely Iran will develop a nuclear weapon in the near future, including 50% who say that is Very Likely to happen. Only 11% say it’s Not Very or Not At All Likely Iran will develop a nuclear weapon soon.

Emre Uslu doesn't think so:

Even if Turkey changes its position and is willing to intervene in Syria, Turkey would not form a collation with the Arab League to conduct such a military operation. There are two reasons for this. First, the Turkish political elite have a deep distrust of the West, especially since the EU abandoned Cyprus and left Turkey alone in many cases. Hence, Turkey would not intervene in Syria because the Turkish political elite think that such action would backfire and open new doors for other countries to intervene in Turkey’s domestic affairs if the Kurdish question gets out of control. For Turkey, there must be international recognition that international force is needed prior to intervention. It seems that US policy makers are trying to build a coalition that consists of the Arab League and Turkey, but this is not enough for Turkey to intervene.Second, Turkey has its own fears. Especially Iranian influence over some proxy organizations in Turkey and Bashar al-Assad’s influence on Turkey’s Alevi community make Turkey think twice when it comes to a military intervention in Syria. Pro-Iranian Turkish journalists, for instance, have threatened Turkey, stating Turkey’s Alevi community is unhappy with Turkey’s policies regarding Syria.

Daniel Larison thinks I'm wrong to guess that Israel will launch an attack against Iran's nuclear facilities. I think his response conflates a question of efficacy (is it a good idea?) and probability (would they do it?). I tend to agree that a strike is probably on balance a bad idea for many of the reasons highlighted in Larison's post.

But I also think that when push comes to shove Israel is willing to tolerate the risks associated with a strike much more than they are willing to tolerate the risks (as they see them) of not attacking.

Update: Noah Millman offers his take:

I think it’s safe to say that there is, essentially, a near-universal consensus in Israel that Iran is developing nuclear weapons, that such a development would be profoundly threatening, and that Iran is unlikely to change course in response to diplomatic pressure. That doesn’t mean the Israeli consensus is right, but that is the overwhelming consensus. That being the case, the political risks to trying and failing are smaller than they might otherwise appear.

I've gotten underway on Aaron Friedberg's new book: A Contest for Supremacy: China, America and the Struggle for Mastery in Asia. One thesis of the book that has surfaced in reviews is that a democratic China would cede the contest for supremacy to the United States. A democratic China, he argues:

would certainly seek a leading role in its region…. But it would be less fearful of internal instability, less threatened by the presence of strong democratic neighbors, and less prone to seek validation at home through the domination and subordination of others.

I personally doubt this, but will keep an open mind until I finish the book. What's interesting is that Friedberg notes approvingly at the outset of Contest that U.S. strategy has long sought to deny the emergence of a dominant power in Eurasia - which makes the U.S., if not a "dominant" power there than at least a decisive one in Eurasia. In other words, the U.S. - a democracy - can have a strategy of exercising robust military power far from its shores to protect its interests. It's not clear to me why a democratic China would forego the same opportunity.

According to a number of published sources, Israel is nearing a moment of truth with respect to military action against Iran's nuclear facilities. No one knows, of course, what action Israel will take (neither, I suspect, do most of Israel's leadership, which appears to be openly debating the proposition as well).

The wisdom of such a move aside, I may as well proffer up my own wild guess as to whether Israel will take military action against Iran's nuclear program. As the title of the post suggests, I'm guessing they will. My reasoning:

1. They've done it before: Both Syria and Iraq have seen how jealously Israel guards its regional nuclear monopoly.

2. They don't believe President Obama will do it: Despite copious threats from U.S. officials, a number of reports indicate that Israel's prime minister does not believe that the U.S. will take military action against Iran.

3. The Arab Spring has made the regional environment worse: Israel's security used to rest on the acquiescence of regional dictators like Egypt's Hosni Mubarak. As the "Arab Spring" produces governments more representative of their public's attitudes, the regional environment is going to get more hostile to Israel. And while Israel can't do much about those developments, they can take a stab at addressing Iran's nuclear program via a military attack - at least in the short term.

As I said, just a guess really, but I'd be more surprised if 2012 (or 2013) passes without an Israeli attack than if one were to occur. What do you think?

(AP Photo)

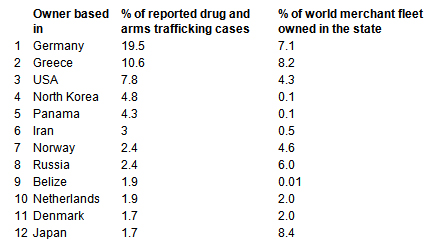

The Stockholm Institute says that ships registered to Western nations are routinely used for running weapons and drugs. In most cases, however, the owners of the ships aren't aware they're being used for smuggling. Thanks to containerization, SI notes, they don't actually know what they're carrying.

Interestingly, the drug war has shown weapons smugglers how to move their goods around:

The report also shows that the methods adopted by arms trafficking networks in response to the UN arms embargoes on Iran and North Korea were pioneered by drug traffickers in the past few decades to evade detection. These methods include hiding the goods in sealed shipping containers that claim to carry legitimate items; sending the goods on foreign-owned ships engaged in legitimate trade; and using circuitous routes to make the shipments harder for surveillance operations to track.

Kori Schake argues that the Obama administration is prematurely writing off the Afghan war:

The evident confusion among senior policy makers in the administration prefigures the administration's cratering commitment to win the war in Afghanistan. The White House has narrowed its war aims from defeating all threats to only defeating al Qaeda. The Director of National Intelligence, James Clapper, testified to Congress this week that the deaths of senior al Qaeda leadership have brought us to a "critical transitional phase for the terrorist threat," in which the organization has a better than 50 percent probability of fragmenting and becoming incapable of mass-casualty attacks.The White House appears set to use progress against al Qaeda as justification for accelerating an end to the war in Afghanistan. Since the president has concluded that we aren't fighting the Taliban, just al Qaeda, no need to stick around Afghanistan until the government of that country can provide security and prevent recidivism to Taliban control. The president will declare victory for having taken from al Qaeda the ability to organize large scale attacks, and piously intone that nation building in Afghanistan is Afghanistan's responsibility.

This policy will not win the war in Afghanistan. It will not even end the war in Afghanistan. It will only end our involvement in that ongoing war.

It's also not clear to me why defeating al-Qaeda is somehow an insufficient standard for victory here. Rather, it is the standard.

Does Schake believe that the Afghan Taliban really have the werewithal or intent to take the fight to the United States once we depart Afghanistan? If Rory Stewart's testimony is to be believed, large numbers of them could not locate the United States on a map.

To the extent that the Afghan Taliban will play host to what's left of al-Qaeda, that is a threat that we can tackle with a far lighter footprint and, yes, no nation building. Complete disengagement would be a mistake. But we need to put the commitment to Afghanistan alongside some rational cost/benefit analysis about the threat we're attempting to mitigate. The danger of an American dying of a terrorist attack on U.S. soil is vanishingly small. It's not zero and will never be zero - no matter how long we stay in Afghanistan and how much money we sink into the place.

In the industrialized world, solar power has struggled to be an economically viable alternative to fossil fuels. But according to a new report from Kevin Bullis, that's no longer the case in the developing world:

The falling cost of LED lighting, batteries, and solar panels, together with innovative business plans, are allowing millions of households in Africa and elsewhere to switch from crude kerosene lamps to cleaner and safer electric lighting. For many, this offers a means to charge their mobile phones, which are becoming ubiquitous in Africa, instead of having to rent a charger.Technology advances are opening up a huge new market for solar power: the approximately 1.3 billion people around the world who don't have access to grid electricity. Even though they are typically very poor, these people have to pay far more for lighting than people in rich countries because they use inefficient kerosene lamps. While in most parts of the world solar power typically costs far more than electricity from conventional power plants—especially when including battery costs—for some people, solar power makes economic sense because it costs half as much as lighting with kerosene.

In congressional testimony, U.S. intelligence officials said that they believed Iran was now willing to launch attacks directly at the U.S. homeland:

U.S. officials said they have seen no intelligence to indicate that Iran is actively plotting attacks on U.S. soil. But Director of National Intelligence James R. Clapper Jr. said the thwarted plot “shows that some Iranian officials — probably including Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei — have changed their calculus and are now more willing to conduct an attack in the United States in response to real or perceived U.S. actions that threaten the regime.”

This is pretty good indicator that, whatever else can be said about the country's rulers, Iran is not driven by suicidal impulses. If Clapper's interpretation is to be believed, Iranian officials haven't been sitting around wondering how to blow up buildings in Boise since coming to power. They have embraced attacks against the U.S. homeland only after the U.S. and its allies have ratcheted up the pressure on them (which, incidentally, does include lethal attacks on Iranian soil).

One of the central arguments sustaining American strategy in Afghanistan is that a failure to stabilize Afghanistan would have disastrous consequences in Pakistan. Proponents of the Afghan surge argued that while Afghanistan may not be strategically worth such a huge investment in blood and treasure, the prospect of instability spilling into nuclear-armed Pakistan warranted the move.

This argument never made much sense and a recent leaked NATO report confirms it:

The U.S. military said in the document Pakistan's powerful Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) security agency was assisting the Taliban in directing attacks against foreign forces.

Pakistan is the architect of instability in Afghanistan, not its victim. It's more than a little ridiculous to argue that we have to fight Pakistan-backed insurgent forces for the sake of Pakistan's security.