The Endgame Cometh

Happy Mujahideen Victory Day.

Nineteen years ago, today, a rag-tag group of insurgents overthrew the previously Soviet-supported Afghan government. It’s a national holiday here in Kabul. The roads, usually clogged with traffic and pedestrians, are clear not only because Afghans are staying home to celebrate but also because many international civilians are on lockdown.

A string of high profile attacks on government and military buildings in the past few weeks have cast a pall over the holiday. And a blockbuster prison break this week has only added to tensions.

But in commemorating a day that was precipitated by the withdrawal of Soviet troops three years earlier in 1989, it’s worth looking forward to how the next major foreign military withdrawal from Afghanistan might shape the country.

Lost in the stories of Taliban infiltration of Afghan security forces has been reporting on how Afghans across the country are starting to hedge their bets as U.S. and coalition forces prepare to drawdown their forces this July, a process that should end by 2014.

Taliban are turning themselves in to authorities to be reintegrated into society, sometimes as part of local militias. Ethnic minority groups are beginning to rearm themselves in anticipation of a return of the Pashtun Taliban. And armies of pundits have weighed in on the false hope of talks with the Taliban or are exasperated that a 10-year war has gone on this long without a diplomatic component to compliment the military hardware.

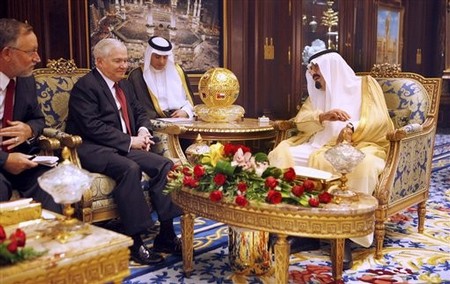

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of all this is what exactly happens after 2014. Ahmed Rashid recently commented on Karzai’s request for a “strategic partnership agreement” with the U.S. after 2014:

The Pentagon is keen on this so it can maintain between two and six bases in Afghanistan to keep pressure on al-Qaeda. Most countries in the region – such as Pakistan, China and Russia – will object to an indefinite U.S. military presence, while Iran will see it as a permanent threat.

The New York Times reports that upon hearing talk of a U.S. presence beyond 2014, Iranian, Indian and Russian officials made a mad dash to Kabul. The Times goes on to explain how talk of long-term U.S. bases could sink the burgeoning peace negotiations:

[The strategic partnership agreement] is without doubt a delicate process, and one that comes at a critical time. Afghan officials have expressed concern that the negotiations could scuttle peace talks with the Taliban, now in their early stages, because the insurgents have insisted that foreign forces must leave the country before they will deal. That they are already talking is an indication they are willing to compromise on the timing of a withdrawal – but it is hard to imagine Taliban acceptance of a lasting American presence here.

Discussions of permanents bases also plays into Afghan conspiracy theories that the U.S. is only here to steal Afghanistan’s mineral wealth and to have a permanent base in the region from which to exert influence over the eventual nuclear state of Iran and the current nuclear power of Pakistan, to say nothing of China and Russia.

A Wall Street Journal piece nicely explores the geopolitical posturing that surrounds an Afghan-U.S. strategic partnership:

Pakistan is lobbying Afghanistan’s president against building a long-term strategic partnership with the U.S., urging him instead to look to Pakistan – and its Chinese ally – for help in striking a peace deal with the Taliban and rebuilding the economy, Afghan officials say…Some U.S. officials said they had heard details of the Kabul meeting, and presumed they were informed about [Pakistan's] entreaties in part, as one official put it, to "raise Afghanistan's asking price" in the partnership talks. That asking price could include high levels of U.S. aid after 2014. The U.S. officials sought to play down the significance of the Pakistani proposal. Such overtures were to be expected at the start of any negotiations, they said; the idea of China taking a leading role in Afghanistan was fanciful at best, they noted.

And yet, Gen. David Petraeus, the top commander in Afghanistan, has met Karzai three times since the Pakistani overture.

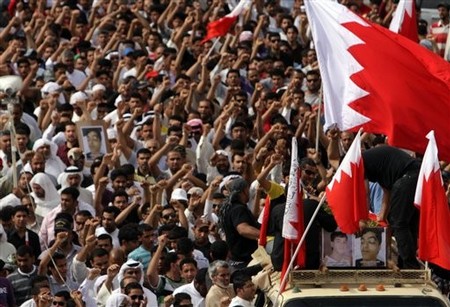

(AP Photo)