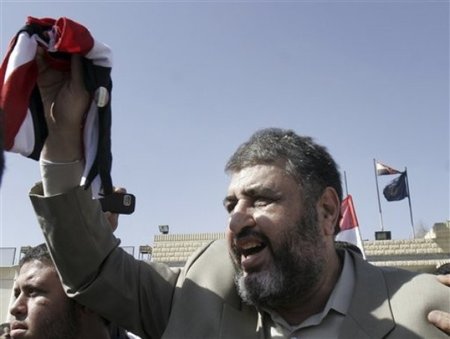

Bill Clinton. John Edwards. Larry Craig. Gary Hart. Elliot Spitzer. Mark Foley. Bill Livingston. Marion Barry. A litany of political leaders who bring to mind scandal and straying, grainy videos and uncomfortable tabloid headlines. Political scandals in America are a rich and entertaining tableau, all the way back to the era of the Founders - sometimes sad, often incomprehensible, and occasionally amusing (Craigslist, anyone?). But the names cited above are all pikers compared to Malaysian politics, where what seems like a conglomeration of all the above scandals are gathered around just one person: Anwar Ibrahim.

Like Edwards and Clinton, Anwar's scandals have put his wife, a prominent political leader, into increasingly difficult and precarious public positions. Like Livingston and Hart, Anwar's scandals have arrived at the key moments in his political career, frustrating his attempts at gaining power. Like Craig and Foley, Anwar's scandals have allegedly involved not just other women but other men - a far more controversial issue in a nation where sodomy is illegal. And like Barry, Anwar now faces a challenge involving grainy video footage from a hidden camera, which could spell the end of his career for good.

As the newspapers in Malaysia cull through the current allegations, the question is whether, like Spitzer and others, Anwar will once again endure the uncomfortable sexual nature of his scandals in the public eye -- or whether these persistent explosive situations, just one of which might have claimed the scalp of an American politician, will eventually drag him down for good.

The first scandal came in 1998, when Anwar, at the time Deputy Prime Minister, had a falling out with his political mentor, Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad. Mahathir had spoken of Anwar as being considered his son, a rising political star and energetic speaker - but they clashed over the direction of the country and a series of policy conflicts coming out of the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Where Mahathir favored price controls, Anwar favored foreign investment and privatization, and opposed bailouts of the banking system. His star was rising too fast for his mentor's liking - in 1998, Newsweek named Anwar "Asian of the Year."

The whole thing boiled over the top at the UMNO General Assembly meeting, where Mahathir released information and lists purporting to show that Anwar had improperly profited off of share allocations from the government during his privatization push. A tabloid book titled "50 Reasons Why Anwar Cannot Become Prime Minister" was distributed, claiming among other things that Anwar was homosexual - a claim he responded to by filing a defamation lawsuit. The lawsuit and the public claims prompted an investigation, a ham-handed show trial, and a verdict: guilty.

The clear lack of evidence and the political context made Anwar into an international martyr. Well-spoken and personally charming, he made political allies in the states - Al Gore, Paul Wolfowitz and others - and was defended by NGOs. Upon his release in 2004, after a panel of judges overturned his conviction based on contradictions in testimony, his path back to politics as a leader of the opposition party was certain.

In the years since, however, more scandals have emerged - all along the same lines and increasingly damaging. In 2008, a former male aide to Anwar came forward to make new allegations of sodomy. Anwar of course denied them, and plead not guilty in court - but this time, the allegations had less of the trumped up feel about them, and while it seems clear the aide was intending to trap the political leader, it's possible he walked right into that, even knowing the risks. In fact, that's exactly what Wikileaks reports that Singapore intelligence authorities believe, writing: "it was a set-up job and he probably knew that, but walked into it anyway."

Yet through all this, Dr. Wan Azizah, Anwar’s wife, has followed the American tradition, standing by her man -- which matters a great deal more in Malaysia, considering that she's president of his PKR Party (imagine if Elizabeth Edwards had been the chairman of the DNC). Even as internal strife in the party and frustration with his attitude toward victimhood caused his allies to consider pushing Anwar aside in favor of less controversial figures, his family connections and charisma have allowed him to remain in prominence. For many, he's viewed as the only person with the prominence to unite the factions of Malaysia's opposition parties to achieve any hope of victory - and as dirty as the mudslinging gets, they're unwilling to cast him off.

Last year, the trial for the second round of allegations began, at the time sparked outrage and complaints from Anwar's allies in America and NGOs. Even if it's possible these latest accusations had more truth to them than the 1998 case, the fact that he had been falsely accused in the past (and the fact that most of us in the West don't think these acts should be a crime anyway) made all the difference.

But those allies have yet to weigh in on the latest allegations, which are plastered on every front page across the country this week: a hidden camera recording which allegedly shows Anwar sleeping around yet again, this time with another woman. Like many religious countries which are normally quiet about such matters in cultural terms, the coverage has been juicier than ever, a rare opportunity to throw off the bounds of conversational restraint. The video was shown by a trio of politically connected men - one a former Anwar insider, another a politician who was himself felled by scandal - who called themselves "Datuk T" (for "Datuk Trio") to journalists and insiders, as well as a gold Omega watch they claimed was seen in the video and belongs to the politician.

Overnight, the national conversation focused entirely on the scandal: Anwar's stern denial (claiming that the man in the "porn video" has a larger belly than he), the police reports and counter-suits, talk of sending the tape to the FBI for analysis or getting local film directors to analyze it, and even claims that the timing of posts to Twitter and Facebook could be used to clear Anwar's name. The details are so numerous, every day brings new reports and topics of debate. And while the opposition claims the ruling party is behind the video scandal, the prevailing opinion among people here seems to be that they would not be surprised if Anwar, in his hubris, was the man.

What's disturbing about all this, of course, is that this martyrdom and scandal has in some ways given Anwar free rein to engage in all sorts of controversial talk and activity, which appeals to his base but would normally put one at odds with the American government. He's stepped up his appeals to anti-Semitic factions, openly intoning about the "Jewish lobby" as one of his foes, and cultivating closer relations with the Muslim Brotherhood - all facts which led Hillary Clinton to (wisely) avoid a meeting the last time she was in-country. Even as he claims Malaysia must follow the example of Egypt, denouncing his foes as entrenched Mubaraks, Anwar's public persona has become all about his scandals, nothing else. The maelstrom around him also serves as a shield, protecting him from further examination of his ideas and proposals, and distracting external groups from statements that might give them pause.

This is a fascinating moment in Malaysian politics. The ruling party is expected to call national elections soon. The opposition leader is embroiled in not one but two explosive sex scandals. For one of America's few truly moderate Muslim allies, what comes next in Anwar Ibrahim's controversial and scandal-plagued career could very well determine the nation's future in the region and the world.

If recent history is any guide, I'd expect more videotape before all is said and done.