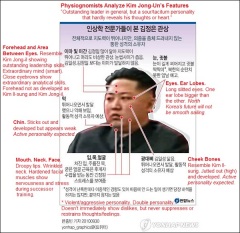

North Korea's Next Leader

The Center for Arms Control and Proliferation has a detailed examination of the face of Kim Jong-un. See the full graphic here.

« August 2010 | Blog Home Page | October 2010 »

The Center for Arms Control and Proliferation has a detailed examination of the face of Kim Jong-un. See the full graphic here.

Elbridge Colby joins the Pletka/Donnelly pile-on, offering his take on what a "conservative" foreign policy would look like:

Pletka and Donnelly have offered an ambitious vision of what the United States' purpose in the world should be. It is magnificent, perhaps, but it cannot be called conservative. In an age in which we must get our fiscal house in order, restore the sources of American prosperity, and face swiftly rising powers whose future courses are uncertain -- above all China -- a conservative foreign policy would focus relentlessly on investing our strategic effort, money, and time to serve our long-term vital interests most effectively. Distinguishing what is important from what is not and making the corresponding tough choices about commitments, spending, and our focus abroad is the heart of a conservative foreign policy. This is the essence of strategy. By contrast, confusing our own future with the fate of freedom in every corner of the world is an invitation to waste, disillusionment, and, quite possibly, disaster.

Well said.

M.S. at the Economist questions China's self-defeating muscle-flexing:

The basic lesson here is that large countries gain influence and power when they adhere to rule-based international systems that give smaller countries a fair shake. They lose influence and power when they act aggressively and unpredictably to extend their own interests at the expense of smaller countries. However, large countries are often swept by tremendous waves of internal nationalism, since their citizens tend not to encounter foreign citizens or media very often, rarely speak foreign languages, and aren't used to the idea that their large and powerful countries may be constrained by anybody else's views or interests. Inside the political systems of large countries, there are usually internal incentives to feed overweening patriotism and nationalism, and to win political battles by accusing rivals of having betrayed the country by being insufficiently aggressive against foreigners. That leads politicians to take aggressive foreign-policy positions which then harm the country's actual interests by provoking fear and antipathy abroad, and generating a counter-reaction. This, at least, is how I can make sense of otherwise inexplicable and self-destructive moves like China's statement that the South China Sea is a "core interest" (the term it also uses for Tibet and Taiwan), possibly committing itself to a negotiating position it can't win and can't back down from. The United States has committed some similarly inept unforced errors over the past decade. But more recently, America has toned down the unilateral nationalism and toned up the rule-based multilateralism. It works.

I think there's one very important difference here: the U.S. wrote most of the rules. China did not.

Michael Auslin isn't sure why they were conducted:

China has claimed the South China Sea as a core national interest, as we’ve repeatedly heard about lately, and is increasing its naval activities, including aerial exercises, in the East China Sea. All the while it refuses repeated requests that it settle territorial disputes in Southeast Asia in an established, transparent, multilateral manner. It would be a shame for one of America’s closest allies, Australia, to now decide to go down the path of paying respect to China’s maritime ambitions in the hopes of influencing its behavior. What the Australians get out of these exercises is difficult to discern. What the Chinese get is clear, as is the message smaller nations in the region receive.

Rory Medcalf offers an explanation:

Any suggestion that practical navy-to-navy cooperation and dialogue means that Australia is somehow slipping into China's strategic orbit and placing less importance on the alliance with the US – or on promising partnerships with Japan, South Korea and India — is wrong. Indeed, HMAS Warramunga's tour of North Asia included a re-enactment of the Incheon landing, a sign of Australian solidarity with South Korea and the US in these tense times on the Korean Peninsula.The bottom line is that there are shared security benefits to be derived from navies getting to know each other better: improved channels of communication, understanding of each other's command systems and ways of operating, even basic awareness of the level of seamanship each side is capable of, all of which can help to calibrate decisions and liaison in a crisis. This applies at least as much to nations that might have clashes of interests at sea as it does to those who see their objectives as generally in harmony. That is why China's reluctance to resume military links with the US has been so self-defeating, and needs to end soon, for everybody's sake.

Every once in a while a commentator will dust off the Wither NATO routine, asking why the U.S. and Europe sustain an alliance whose central rationale - deterring the Soviet threat - disappeared decades ago. A staple argument is that NATO risks becoming "irrelevant" as European defense budgets shrivel and some members bear unequal burdens in Afghanistan. But I think these arguments overlook an important point. If you want to know why NATO endures, I think this interview with Condoleeza Rice sheds some good light on Washington's thinking:

SPIEGEL: But Americans insisted on full NATO membership for the unified Germany. It was very unlikely that Gorbachev would swallow this. Weren't the Americans trying to block reunification this way?Rice: No. But we couldn't afford in the end game of the Cold War to make a bad misstep. And a really bad misstep would have been to pull Germany out of NATO, which would have collapsed the most important platform for the American presence in Europe.

SPIEGEL: But who could really believe that the Russians would ever agree to that?

Rice: There were debates in the American foreign policy establishment that maybe both the Warsaw Pact and NATO should go away. But we at the White House never considered the possibility of unifying Germany outside of NATO. It would have meant that at the last minute, with everything going our way, the United States capitulated on the essential thing in terms of the American presence in Europe. [Emphasis mine]

And again at the end:

SPIEGEL: In retrospect, what would you have done differently during the negiations about the unification process?Rice: I'm sure there were small tactical things that could have been done differently, but how could it have come out better? Germany fully integrated and united with its democratic institutions intact, integrated in Europe, integrated in NATO and the American presence is secure in Europe. [Emphasis mine]

Whatever other rationales are offered up for why NATO remains relevant, it's central, animating purpose is to keep America immersed in the affairs of Europe. Seen in this light, Europe's collective decision to continue to sacrifice defense budgets on the altar of austerity is a feature, not a bug.

Speaking at a dinner of American and Chinese businessmen in New York last week, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao said the China-U.S. relationship “enjoys a bright future because common interests between our two countries far outweigh our differences.” But just 32% of Americans agree.A new Rasmussen Reports telephone survey finds that 30% of Adults do not share the premier's view of common interests, and 38% are not sure. (To see survey question wording, click here.)

Most Americans agree, however, that U.S. relations with China are important. Eighty-three percent (83%) think the relation between the two nations is at least somewhat important, including 53% who think it is Very Important. Just nine percent (9%) think relations between the two are not important. This remains unchanged from nearly a year ago.

Still, an overwhelming majority of Americans (87%) are concerned about the level of U.S. debt now owned by China, including 61% who are Very Concerned. Just nine percent (9%) are not very or not at all concerned.

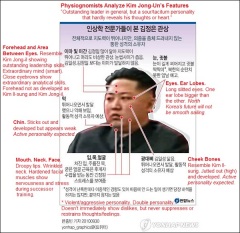

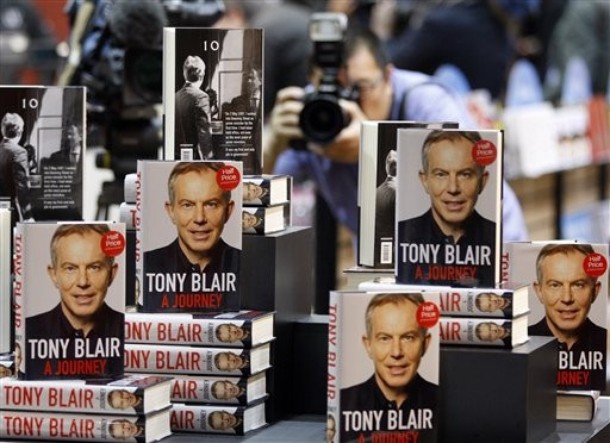

(AP Photo)

Matthew Yglesias argues that the reason Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu hasn't embraced an extended freeze on settlement building is because he is committed to settlement building. A bit simplistic, yes, but I wonder if we haven't gotten so far off into the peace process trees that we're overlooking (or ignoring) the forest.

The U.S. tends to behave as if the desire for peace is so self-evident and that perpetuating the status quo is so obviously intolerable to both parties that they'll eventually concede to the wisdom of a negotiated settlement, however painful some concessions may be.

But at a certain point we may have to accept that the fact that the parties want something else (settlements, right of return, control of Jerusalem, etc.) more than whatever compromise peace Washington can conceive of.

Walter Russell Mead does a nice job shooting down Thomas Friedman's contention that electric cars are the key to rejuvenating American manufacturing and the middle class. To just add a bit to Mead's case, the idea that electric cars will transition America off of "foreign sources" of energy and help us compete with China is simply not true. As frequent RCW contributor Daniel McGroarty has tireslessly pointed out, the batteries we'd be inserting into those electric cars rely on Rare Earth minerals to function. And guess who has the bulk of those minerals?

China.

(AP Photo)

Some have suggested that we should simply learn to live with a nuclear Iran. In my judgment, that would be a grave mistake. And as one Arab leader I recently spoke with pointed out, how could anyone count on the United States to go to war to defend them against a nuclear-armed Iran, if we were unwilling to go to war to prevent a nuclear-armed Iran? - Sen. Joe Lieberman

I honestly could not think of a worse argument on behalf of bombing Iran than the idea that it must be done on behalf of the various despots of the Arab world who are too afraid or weak or corrupted to do it themselves.

According to Pew Research, Brazil is (mostly) all smiles about its position in the world:

...half of Brazilians say they are satisfied with national conditions, and 62% say their nation's economy is in good shape. Of the 21 other publics included in the 2010 Pew Global Attitudes survey, only the Chinese are more upbeat about their country's overall direction and economic conditions....

Brazilians also hold favorable opinions of the U.S. and China, the country's two biggest trading partners. About 62 percent of Brazilians give the U.S. a favorable rating, while 52 percent give China one. Interestingly, while Pew found that Brazilians give outgoing President da Silva high marks, they disagree with his handling of Iran:

The president has opposed additional international economic sanctions against the Islamic Republic. Yet, of the 85% of Brazilians who oppose Iran acquiring nuclear weapons, nearly two-thirds approve of tighter sanctions to try to prevent it from developing such weapons; 31% oppose tougher economic sanctions against Iran.1 Majorities of those who oppose a nuclear-armed Tehran in 18 of the other 21 countries surveyed also endorse such a measure.In addition, most (54%) Brazilians who do not want to see a nuclear-armed Iran are willing to consider the use of military force to prevent Iran from developing nuclear weapons; a third say avoiding a military conflict with Iran, even if it means it may develop these weapons, should be the priority.

Overall, Brazilian views of Iran are among the most negative of the 22 publics included in the 2010 Pew Global Attitudes survey.

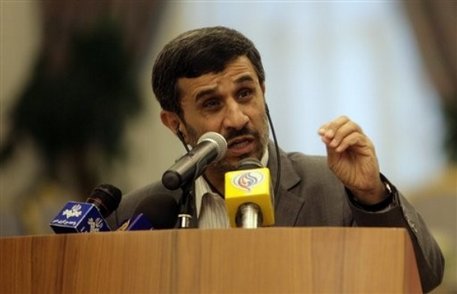

(AP Photo)

China has long been recognized as the key player in the effort to isolate and pressure North Korea to give up its nuclear program. But it appears that Beijing is more interested in "investing" in the Hermit Kingdom than denuclearizing it:

China has launched a major push to boost economic engagement with North Korea and persuade Pyongyang to adopt reforms, experts say.Analysts suggest Beijing believes development will improve regional stability by encouraging its impoverished neighbour to act more cautiously.

China also hopes to benefit from port access, mineral rights and increased trade.

But some believe the economic drive undercuts the impact of sanctions imposed in the hope of forcing North Korea to denuclearise.

From China's perspective, stability at the border and a buffer between it and U.S.-aligned South Korea matter more than whether the country has a few crude nuclear weapons or periodically engages in bouts of international blackmail. Until Washington can devise a way to change that calculus, we're going to be stuck with the Kim clan for a while longer.

(AP Photo)

The results of Sunday’s National Assembly elections in Venezuela were not announced until well past midnight early Monday morning: The opposition won over 52% of the vote but did not win the majority in the National Assembly. However, the opposition won 60 seats, ending the two-thirds super-majority Hugo Chávez needed to slide his projects through.

Chávez was hoping for a crushing win that would propel him to a victory in next year’s presidential election. Instead, his party kept only 94 seats, in spite of extensive gerrymandering that favored candidates from Chávez’s party, Chávez’s unlimited use of state funds for their campaigns, and his constant television access.

By Tuesday morning, Chavez was claiming that his party beat the opposition by a slight margin in the overall vote, contradicting early reports. The Wall Street Journal points out,

The different interpretations of the nationwide vote count are likely explained by the fact that the opposition includes the political party PPT. The PPT, a leftist group that only won a couple of seats Sunday, has traditionally supported Chavez, but had a falling out recently.With the economy in a deep recession, one of the highest inflation rates in the world (30% in the last year), soaring violent crime, and electricity shortages, voter turnout reached 66%. The opposition had sat out the prior National Assembly elections in 2005. This time they were able to gather the majority of the vote, if not the National Assembly seats. Currently holding barely 10% of the National Assembly seats, they now won over 33%.

The new congress will probably not rubber-stamp laws that increase Chávez’s power, but this does not mean Chávez will take it as a defeat. He has stripped of power the office of the mayor of Caracas when an opposition politician won two years ago and jailed the general who returned him to power after a coup; he still controls the courts and the majority of the states; he has nationalized private industries and the media; and the new National Assembly members won’t be seated until January, affording him time to push changes through.

Goldman Sach’s Alberto Ramos (link by subscription only) expects that Chávez “will probably resort to govern even more by decree which jointly with a friendly judiciary can contribute to debase the importance of the Assembly in the country’s institutional balance of power.”

Yet another factor is oil: Venezuela is the U.S.’s fifth-largest oil supplier. As its oil production continues to decline, Chávez may not have the financial muscle to back his thirst for power.

Will this strengthen the opposition and possibly lead to a more democratic outcome in the 2012 elections?

It is too soon to tell.

Elizabeth Economy argues that China isn't just rising, but ageing:

Chinese officials appear most concerned about the ageing of the population. They face two separate challenges here. First, by 2050, China will have more than 438 million people over the age of 60, roughly 25 percent of the country’s total population. China’s leaders are desperately concerned about maintaining a strong and active labor force to ensure continued economic growth. Of course, people over 60 can continue to lead productive lives, working well into their seventies or even eighties, but China will need to improve its health care system to ensure their health care needs are met in the process.Second, the skewed age demographic has brought about the “Four-two-one” problem, in which one child is responsible for caring for two parents and four grandparents, has been actively discussed for well over a decade. With a dearth of facilities to help care for the elderly, there is no doubt that the burden will be great on these only children, and recent polls suggest that many do not feel prepared to shoulder such a burden—even simply to take care of their parents, much less their grandparents.

Meanwhile, the Telegraph marks the 30th anniversary of China's "one child" policy:

But today, the one-child policy remains firmly in place and government officials cannot shake the idea that it has played an important role in China's economic miracle.With only one child to care for, parents have been able to save more money, enabling banks to make the loans that have funded China's huge investments in infrastructure.

Meanwhile, officials claim the policy has conserved food and energy and allowed each child better education and healthcare.

"We will continue the one-child policy until at least 2015," said the National Family Planning Commission earlier this year.

World Public Opinion and the BBC teamed to gage the views of people in 22 countries on taxes. The results:

The poll of more than 22,000 people, conducted by GlobeScan/PIPA, found that people estimated on average that 52 per cent of the money they pay in tax is not used in ways that serve the interests and values of the people of their country.Despite this lack of trust in government to spend tax money responsibly, the poll found on some measures there is a near global consensus for increased government action. Nearly four in five around the world (78%), and majorities in all but one of 22 countries polled, think that government should subsidise food to keep prices for the consumer down, with only 18 per cent disagreeing. Two-thirds overall (67%), and majorities in 19 out of 22 countries, think that government regulation and oversight of their national economy needs to be increased--the US, Turkey and Spain are the only exceptions.

Other government interventions achieve slim majority support. In 14 of 22 countries most people--on average 56 per cent--favour an increase in government spending to stimulate the economy. This includes large majorities of Egyptians (91%), Mexicans (80%), Russians and Indonesians (both 78%), and Nigerians (73%). But majorities are opposed in a number of industrialised countries that had large stimulus programmes--Germany (66%), France (63%) and the US (58%).

On average 51 per cent also want their government to take steps now to address their deficit and debt, while 39 per cent are opposed. The United Kingdom is among the countries where support for deficit reduction measures is higher, at 60 per cent. Asked whether they would prefer their government to focus on tax rises or service cuts in dealing with their country's deficit and debt, in every country but Egypt more people said they preferred a focus on cutting services (on average 54%) than on increasing taxes (14%).

Full results here. (pdf)

In New York City this past weekend, discussion surrounding the US-ASEAN summit has inevitably turned to the topic of moderate Islam, and what role nations like Malaysia will play in the future as relates to the foreign policy interests of the United States. I've written about this issue before, and it's worth noting the remarks made by Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak in his maiden address to the United Nations General Assembly today, in which he called for a "Global Movement of the Moderates" to reclaim the public square from, as he sees it, radicals and extremists who misrepresent the ramifications of their faiths:

"It is time for moderates of all countries, of all religions to take back the centre, to reclaim the agenda for peace and pragmatism, and to marginalise the extremists."This Global Movement of the Moderates will save us from sinking into the abyss of despair and deprivation," he said.

Expressing concern with the increasing trend in some parts of the world to perpetuate or even fuel Islamophobia, the prime minister said it had intensified the divide between the broad Muslim world and the West.

"The real issue is not between Muslims and non-Muslims but between the moderates and extremists of all religions, be it Islam, Christianity or Judaism."

He said all religions had inadvertently allowed "the ugly voices of the periphery to drown out the many voices of reason and common sense".

Najib is staking some progressive ground here in making this call for stability and moderation, and he's one of the few leaders in the Muslim world who can do so. The question that this raises, assuming you agree with his view, is how this public square might be reclaimed without rough tramping over free speech and other individual rights. It is far more appealing for the news cameras, after all, to talk to the lone pastor who wants to burn books than the thousands who do not.

Finding this balance is important. The fact that such a call can be made now - not by the West, but by a key Muslim political leader - is at least a positive sign.

(AP Photo)

One of the arguments that runs through the Obama administration's Afghan strategy debate (as recounted by Bob Woodward) is the idea, advanced by the U.S. military, that killing Afghans in pursuit of al-Qaeda and the Taliban is counterproductive without a broader effort to assuage their grievances and improve their country :

At the Nov. 11 meeting in which Obama expressed his frustration, Petraeus cited the war game as evidence that the hybrid option would not work.It would alienate the Afghan people whom U.S. forces should be protecting, he said. "You start going out tromping around, disrupting the enemy, and you're making a lot of enemies. . . . So what have you accomplished?"

This makes sense. If you're just dropping bombs and assassinating people in a country without regard for much else, they're going to be resentful and seek retaliation. But why is this understanding never advanced to the strategic level? The terrorist threat to the U.S. is global. If we're so solicitous of Afghan civilians that we're willing to risk over 100,000 U.S. and NATO troops and invest billions of dollars into the country to guard against blow back, shouldn't we be considering the ramifications of U.S. policies elsewhere?

(AP Photo)

Yoree Koh says that the Japanese government has come out swinging today against China by demanding payment for damage done to their vessels by a Chinese fishing boat in addition to ordering more Chinese fishing patrol boats away from the contested Senkaku islands and summoning the Chinese ambassador for a talking to.

If you're interested in what the fuss is all about, Global Security.org has a good primer on the actual islands in contention.

(AP Photo)

This report on the Iraqi government's decision to strip Anbar Awakening members of their police ranks highlights the difficult position the U.S. is in with respect to Iraq. On the one hand, it's clearly bad news, as it appears to be sectarian score settling by the central government. On the other hand, is it really our role to tell the Iraqi government who can and who can't be a police officer?

Zakaria, in his final column for Newsweek, elaborates on Turkey's new foreign policy.

According to a report in the China-owned Xinhau newspaper, Pakistanis living in the tribal zone have begun taking sedatives to help them sleep through all the drone attacks. Like so much about the quasi-secretive drone campaign, it's hard to tell if this is true or not.... but it doesn't sound surprising.

Daniel Larison offers some further thoughts on the freedom and defense spending debate:

Not only did a host of other factors contribute to the end of the USSR, but in most important respects it was overwhelmingly the political action of the peoples of eastern Europe and the USSR that resulted in the collapse of the Soviet system. This isn’t meant to diminish the real successes of containment policy in western Europe and Asia, but we do need to acknowledge that policies that provided effective defense for our allies also effectively did very little to advance the freedom the hundreds of millions of people under Soviet control. That wasn’t the purpose of containment, and neither was it the main purpose of the military build-up in the ’80s.Besides, to the extent that our military build-up showed leaders in the USSR that their economic and political model could not compete and thus contributed to the collapse, it is not something that can be readily repeated today and it is not something that needs to be repeated. Even if one wants to maintain that the build-up in the ’80s was imperative to “winning” the Cold War, there is no comparable competing state today, nor is there likely to be one for a long time. What Pletka and Donnelly are calling for is the ability to project power around the world in ways that have no connection with the advance of political freedom abroad. They are arguing for a “robust” American role in a post-Cold War world where it is not needed. Indeed, it is less necessary today than it was ten or twenty years ago, and it will become increasingly outdated and unnecessary as more regional powers begin assuming responsibility for their parts of the world.

Even in the world of diplomacy, there are times when language has to be clear and unmistakable – like after a flag is mistakenly displayed in a way to imply there is a state of war.The Philippine flag was displayed upside down behind President Benigno Aquino III when he met with President Obama and other leaders of the Assn. of Southeast Asian Nations on Friday. - Los Angeles Times

(AP Photo)

Colombian terrorist Mono Jojoy, military commander and No. 2 guy of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), who also was believed to have been in charge of their cocaine-trafficking operations, was killed by the Colombian military last Tuesday, Sept. 21.

After evading justice for over a decade, the Colombian armed forces, with the help of American military training and technology, were able to locate Mono Jojoy through his boots. Jojoy, also known as Jorge Briceño, whose real name was Víctor Julio Suárez Rojas, was diabetic and needed special shoes since the diabetes affected the circulation on his feet.

According the Colombian newspaper El Espectador (in Spanish), Colombian intelligence intercepted an order for Mono Jojoy’s boots and placed a GPS chip, which started transmitting his precise location on Monday.

The ensuing raid on his camp was an all-out military operation, code name Sodoma (Sodom), involving dozens of aircraft and three tons of explosives. Following the raid, the Colombian military found 15 laptops, 94 USB devices and 14 hard disks, which will yield vital intelligence on the FARC’s operations.

This is a huge coup for Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos and the Colombian government and a most crippling blow against the FARC. Mono Jojoy was not only a symbol of the FARC, but also directly involved in the FARC’s military (allegedly in charge of of some 4,000-plus members), kidnapping and cocaine-trafficking operations, and left no clear successor.

Mono Jojoy’s body was identified through his fingerprints. He was wearing his Rolex and carried insulin in his pockets at the time of the raid.

Mono Jojoy had a prize on his head of U.S. $5million, and had been indicted in the U.S. for the murder of three U.S. citizens, drug trafficking and terrorist activities. Four people will share the reward.

UPDATE:

After I posted this article, Spanish newspaper ABC reported that General Javier Flores, in charge of the military operation, asserts that Mono Jojoy was found from information provided by an undercover officer that infiltrated the FARC's high command. This is even worse news for the FARC.

Fausta Wertz blogs at Fausta's blog.

(AP Photo)

Responding to my assertion that there's no correlation between U.S. defense spending and global freedom James Joyner (and Dave) called me out - arguing that the demise of the Soviet Union proves that indeed there is.

That's true, and I concede the point - up to a point. First, the U.S. defense build-up had an impact on the Soviet Union's ability to compete with the U.S. and helped hasten their end - but a host of other factors contributed to that end as well, as Joyner admits. If the Carter and Reagan administrations didn't initiate a defense build-up but the Soviet Union was still battered by falling oil prices and the Afghan insurgency (not to mention the accumulated rot of the Soviet system) would they still have fell? I'd argue that they would have, although, yes, it was useful to give them a push.

But to make the argument that global freedom hangs in the balance unless we transfer even more U.S. wealth to the Pentagon shouldn't the casual links be a bit tighter? And shouldn't there be more than one example?

Still, as I said, I'd certainly concede that the 1980s defense build-up did play a role in cracking the Soviet Union which in turn helped liberate Eastern Europe. I wonder, though, what relevance this has for 2010's strategic debates. Indeed it seems to put the Pletka/Donnelly argument in a worse light. The U.S. doesn't face a conventional military challenge on par with the Soviet Union and if you don't think spending billions of dollars in nation building and counter-insurgency is a sensible counter-terrorism policy, it's hard for me to see the point of declaring any and all defense cuts verboten, much less an intolerable threat to our very freedom, or the freedom of others.

The Hindu has a good interview with Mani Shankar Aiyar - a former Petroleum and Natural Gas minister on India's quest for energy security in a booming Asia.

Judah Grunstein wonders:

Everyone loves a soft, cuddly Middle Power with a domestic track record of poverty reduction and a global image of multilateral, if not servile, diplomacy. But things tend to change when hard power gets deployed in defense of national interests. In mathematical terms, the question facing Brazil and the world is, Brazil:South Atlantic = China:South China Sea?

If I'm reading this op-ed from Danielle Pletka and Thomas Donnelly correctly it sounds like they don't want the Republican party (or the Tea Party) to cut defense spending. Which is fine, so far as it goes. But they also seem to insist that the desire not to cut defense spending is somehow tied to protecting "freedom" at home and abroad.

Is there a correlation between U.S. defense spending and global freedom? There doesn't appear to be: in the period 1990-2000, as U.S. defense budgets fell, the number of countries ranked "free" by Freedom House grew slightly. Since 2000, as defense budgets grew, the number of countries ranked "free" stayed pretty much the same - the trend lines toward greater global freedom had actually turned negative during the years 2006-2009.

In other words, if you want to make an argument for why the U.S. should continue to devote plus or minus X amount of dollars to defense expenditures, I don't think "freedom" has much to do with the case one way or the other.

(AP Photo)

Trying to occupy and govern foreign societies that are rife with internal divisions, where there is a well-founded hatred of foreign intruders, wouldn't be easy for anyone. Indeed, trying to create a political system there based on our historical experience rather than theirs has got to be one of more ambitious -- if not utterly misguided -- objectives that Washington could have picked....The solution is not to retreat into isolationism and cede the initiative to others. Rather, the solution is to remind ourselves what American power is good for, and avoid taking on tasks for which it is ill-suited. The United States is very good at deterring large-scale aggression, and thus good at ensuring stability in key regions. (That assumes, of course, that we aren't using that same power to destabilize certain regions on purpose). We are sometimes good at brokering peace deals -- as in Northern Ireland and the Balkans -- when we use our power judiciously and fairly. And we've often done a pretty fair job -- in concert with others -- at encouraging intelligent liberalization of the world economy. The United States is not very good at governing foreign societies, especially when the local inhabitants don't want us there and when we have little understanding of how they work. And if we keep trying to do this sort of thing, we're likely to look inept far more often than we look effective. - Stephen Walt

A new poll from the Jerusalem Media and Communications Centre offers a glimpse into Palestinian attitudes toward the peace process:

A public opinion poll released Thursday suggests that just over half of Palestinians support negotiations with Israel.But a larger majority, 59 percent, say Palestinians were coerced into entering the talks, the first since 2008. Only one-third of respondents believe the negotiations will succeed, according to the poll conducted by the Jerusalem Media and Communications Center.

Similarly slim majorities (52.9 percent) believe negotiations are the most effective strategy to achieve their national goals, compared with 25.7 percent who say violent resistance is a better route and 15.7 percent preferring non-violent resistance.

A willingness to negotiate rather than resist is a positive, but it would have been just as useful to get numbers on what Palestinians see as the "national goals" that they wish to negotiate toward.

UPDATE: Scratch that last part, the poll did put the question of national goals on the table. Slim majorities in the West Bank (54.7 percent) and Gaza (51.3 percent) favor a two state solution vs. 30 percent in both territories that favor a bi-national state and a further 4 percent in the West Bank and 9.6 percent in Gaza who would prefer single Palestinian state encompassing all the territory. Thanks to commenter HDarrow for pointing this out in comments.

Picking up on Greg's post, it seems as though the GOP's "Pledge to America" is rather slim on foreign policy altogether. As an American voter, I actually find this appealing; domestic politics should be the focus of the 2010 elections, and kudos to the Republicans - if this leaked version of the party's 2010 electoral strategy is accurate - for making those issues their central focus.

That said, the foreign policy news junkie in me is somewhat disappointed in the dearth of red meat offered in this plan. It also begs a question: with all of the huffing and puffing we have heard - and indeed continue to hear - from conservatives about Obama's "appeasement" of Iran, are these same critics thus satisfied by a short and simple pledge to enforce "tough sanctions against Iran"?

I believe this demonstrates just how easy it is to be one of the two main political parties on the outs in the United States. Ideological rigidity, or, in the specific case of Iran, radical statements about preparing for a regime change, make for good soundbites and exchanges on the Sunday morning shows, but they don't resemble, as far as I can tell, the actual Republican plan for governance regarding the Islamic Republic - and that's a good thing.

All this could change, of course, in 2012 . . .

(AP Photo)

The leaked copy of the GOP's "Pledge to America" has absolutely nothing to say about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, much less any of the usual boilerplate about victory. Curious, no?

I suspect that some in wealthier countries may ask, with our economies struggling, so many people out of work, and so many families barely getting by, why a summit on development? And the answer is simple. In our global economy, progress in even the poorest countries can advance the prosperity and security of people far beyond their borders, including my fellow Americans. - President Obama

I remember a standard liberal complaint during the Bush administration was that said administration engaged in a lot of fear-mongering. But the Obama administration is proving no different. If every charitable or environmental effort you favor is going to be draped in the language of "national security" than the term has no meaning.

Gallup's annual Governance survey finds 57% of Americans expressing a great deal or fair amount of trust in the U.S. government to handle international problems. That is down from 62% a year ago, but remains higher than the percentage trusting Washington to handle domestic problems, now at a record-low 46%.

If all these policies were aimed to achieve an effective sanctions package against Iran with Russian support, then the "reset" policy failed. The sanctions, as advertised, will not be able to stop the Iranian race to gain nukes.The reported US capitulation on S-300 is the latest in the long list of unilateral concessions to Russia, which endanger US friends and negatively affect US national security. - Ariel Cohen, "If the S-300 Sale is Allowed, Obama’s Russian “Reset” Policy Has Failed"

Russian President Dmitry Medvedev issued a decree Wednesday banning all sales of S-300 anti-aircraft missile systems to Iran. - AP

Marc Theissen is outraged that President Obama reportedly said that the U.S. could "absorb a terrorist attack."

These are stunningly complacent words from the man responsible for stopping such a terrorist attack. Obama uttered them last July, after America suffered two near-misses—the failed attacks on Christmas Day and in Times Square. Rather than serving as a wake-up call and giving the president a sense of urgency, these attacks seem to have given the president a sense of resignation. He is effectively saying: an attack is inevitable, we’ll do our best to prevent it, but if we get hit again—even on the scale of 9/11—it’s really no big deal.In fact, it would be a big deal, particularly to the people who would bear the burden of “absorbing” another attack—the victims and their families. Obama’s statement is unimaginably cavalier about the deaths of nearly 3,000 people, and disturbingly resigned to the prospect of thousands more perishing in our midst.

First, what President Obama said seems correct. The U.S. can absorb a conventional terrorist attack and continue to function (a WMD attack would be a different story, but fortunately those are much harder to pull off). It's not as if President Obama is suggesting an attack is a good thing or that we should encourage them. In a free society, it's impossible - impossible - to stop every last individuals or small groups of people from committing acts of terrorism. Pretending otherwise, as Theissen appears to, is not only naive but infantile.

Now, the other point is whether this means the administration is "complacent" and "resigned" to future terrorist strikes. If one defines counter-terrorism as consisting of a set of policies beyond torturing people enhanced interrogation, I think it's hard to argue that they are. There's been an expedited drone war in Pakistan, a surge of troops into Afghanistan, and an uptick in not-so-covert support to Yemen and Somalia. One would not embark on those policies if they took a blase attitude about the threat from al-Qaeda.

(AP Photo)

Everyone's aflutter over the new Bob Woodward tome documenting rifts in the Obama administration's war cabinet over the war in Afghanistan. In the early write-ups it appears that key members of the administration had serious misgivings about the counter-insurgency strategy championed by the military and many outside experts. Writing in Foreign Affairs, Ben Connable explains what is necessary for the U.S. to stabilize Afghanistan, and reading it, you understand the misgivings of folks like Holbrooke and Eikenberry:

If the United States seeks stability in Afghanistan, its strategy will have to deal with these realities. There can be no shortcuts; although it is possible to quickly defeat insurgents, dealing with root causes, a multitude of combatants, and havens will take time. And it will be expensive: the costs of such an effort are incalculable, since it is impossible to predict how long the violence in any insurgency will drag on.Nevertheless, a careful study of insurgencies over the last 50 years suggests that what is needed in Afghanistan now is the patient application of a traditional counterinsurgency campaign for years to come. If done well, a long-term campaign could lead to a stable Afghanistan that is so inhospitable to the major Afghan insurgent groups that they wither into irrelevance or are forced to the bargaining table. Enduring stability in Afghanistan and a consequent shift in popular support for the government could, on balance, negate the strength the Taliban continues to draw from its sanctuary in Pakistan. And although a successful counterinsurgency campaign in Afghanistan will not ultimately solve the problem of terrorist sanctuaries in Pakistan, neither do any of the other proposed policy options.

In other words, no one knows how to dry up terrorist sanctuaries in Pakistan. But even with a stable Afghanistan, secure safe havens in Pakistan will allow al-Qaeda to strike at American targets, even if fitfully and largely unsuccessfully. It seems to me that if we can't safeguard the U.S. from terrorist attacks emanating from Pakistan no matter what we do in Afghanistan, than we should not pursue a strategy with the highest costs associated with it.

It's not everyday that I agree with what Tom Friedman says about China. Typically, he goes there, gets starry eyed, and starts extolling all the virtues of the Chinese Communist Party.

His column today wasn't quite that. And he was 100 percent correct on why China gets things done whereas the U.S. no longer does.

This was right on the money:

Studying China’s ability to invest for the future doesn’t make me feel we have the wrong system. It makes me feel that we are abusing our right system. There is absolutely no reason our democracy should not be able to generate the kind of focus, legitimacy, unity and stick-to-it-iveness to do big things — democratically — that China does autocratically. We’ve done it before. But we’re not doing it now because too many of our poll-driven, toxically partisan, cable-TV-addicted, money-corrupted political class are more interested in what keeps them in power than what would again make America powerful, more interested in defeating each other than saving the country.

Once upon a time the U.S. did build Interstate freeways that traversed the entire continent. Dams that regulated water flow and generated power. Skyscrapers that were the envy of the world. And all that was done in a free society and under democratic governance.

(Just the other day a friend and I joked about the L.A.-to-San Francisco bullet train, something that's been "in the works" for more than 20 years and yet not a single rail has been laid. We concluded that our grandchildren will still be talking about it 50 years from now.)

Nothing gets built anymore in the U.S. - other than sports stadiums. Too much red tape. Too many lawyers. Special interest groups. Unions. By the time an environmental impact study was done, a new one has to be commissioned. In the meantime, China just finished adding another thousand miles of high-speed railway.

Another valid point Friedman made about China is its leadership. The top of the CCP leadership chain is frighteningly competent. To rise to the pinnacle in China these days, you can't do it with catchy slogans or being the son of a former president.

Hu Jintao is an engineer by trade. Wen Jiabao a geologist. The fifth-generation CCP leaders have even more diverse backgrounds after a generation dominated by engineers. Many have PhDs and a great number of them are now foreign-educated.

But Friedman does miss a point (perhaps on purpose). With a near-homogeneous population (91 percent Han Chinese), China doesn't have diversity issues; and its benevolence toward minorities is purely lip service.

In the Chinese view, somewhat tinged with racism, the U.S. and the west are being dragged down by their minority populations and racial strife. But the reality is that it's not the blacks and Latinos that are impeding progress in the U.S., as the Chinese are wont to believe (a same attitude held by the Japanese, especially when it was booming in the '80s), it's the diversity-driven politics that are long on sensitivity but short on competitiveness.

That's part of the recipe for the hamburger that may ultimately do the U.S. in.

Dan O'Brien reports:

After two decades of population growth, Ireland’s long-term pattern of decline looks set to resume.Ireland is demographically unusual in three distinct ways: in its mobility, its mortality and its fertility. Last year, among the 27 EU member countries, Ireland had the highest rate of outward migration, the lowest death rate and the highest birth rate. In the year to April, according to figures released yesterday, a surge in net emigration came close to overwhelming the other two factors.

Last year, after many years of new arrivals exceeding departures, net human flows to and from this country went sharply into reverse. According to the EU’s statistical agency, nine in every 1,000 people left. This was double the rate of the country with the second highest emigration rate – recession-ravaged Lithuania. Of the 15 rich, long-term members of the EU, Ireland was one of only two to experience net emigration.

New figures released yesterday show that more than 65,000 people left the country in the year to April. Although this was only slightly more than in the previous year, the breakdown by nationality was very different. Most notable was a 50 per cent surge in the number of Irish people departing. This is in contrast to the earlier phase of the recession, when most of those relocating were immigrants from the new EU member countries returning home.

Meanwhile, Michael Schuman examines Ireland's vulnerability to a Greece-style sovereign debt crisis.

There seems to be two emerging themes to America's post-recession national security debate. The first, typified by the Obama administration, is that the U.S. must continue to do everything globally but on a tighter budget and with help from allies. Secretary Clinton rebuffed advocates of restraint in her recent speech at the Council on Foreign Relations:

Which of our great challenges today can be placed on the back burner? Are we going to tell our grandchildren that we failed to stop climate change because our plate was just too full? Or nuclear proliferation? That we gave up on democracy and human rights? That is not what Americans do.

In other words, whatever the administration says about husbanding American resources and rebuilding on the home front, they're still committed, at least rhetorically, to over-stretch.

Then there is the conservative counter-thrust, which is to argue that America must continue to do everything (and more, like bombing Iran) but on a bigger budget - deficits and economic constraints be damned. Hence the continued outrage at Secretary Gates' efforts to redirect the growth of defense spending (which actually won't result in cuts to the defense budget, but in an internal shift in how resources are spent).

Reading this Seth Cropsey piece* on the U.S. Navy reinforced my view that there is a third way - that a constrained U.S. has to do better at picking its spots. This means focusing investment where it will yield the biggest returns and where the international system, and American interests, are most at risk.

Right now, the two poles in the debate oscillate around the worst of all possible worlds. The Obama administration evinces a kind of schizophrenic attitude - paying lip service to the idea that the U.S. needs to shore up its domestic position but insisting it can do so while sustaining America's post-Cold War posture as if nothing has changed (and spare us the talk of allies "doing more" - since when?). The administration's critics, meanwhile, are on red-alert for any hint of walking back any commitment, anywhere.

(*Cropsey himself doesn't appear to be in this third way camp, he insists that the U.S. has to be strong everywhere for the sake of "great power prestige" - I don't know about you, but it gives me a warm feeling to know my tax dollars go to making Washington bureaucrats feel prestigious. But Cropsey, whose piece makes the pitch for a strong navy, reinforces the point that the U.S. has become too focused on land wars and counter-insurgency. Neither will do much good to deter China, should the need arise.)

Angus Reid surveyed British, American and Canadian views of the peace process:

A large proportion of respondents in the three countries do not express sympathy for either of the two sides in the Middle East dispute. Americans favour Israel over the Palestinians (27% to 5%), while Britons pick the Palestinians ahead of Israel (19% to 10%). Canadians are evenly divided in their assessment (13% for Israel; 13% for the Palestinians).Respondents in the three countries were also asked about the sympathies of their respective heads of government. Canadians clearly think of Stephen Harper as pro-Israel (36%) and Britons feel the same way about David Cameron (21%). In the United States, 18 per cent of respondents think Barack Obama sympathizes more with the Palestinians, while 15 per cent believe he is more considerate to the Israelis.

A large majority in all three countries feel the talks won't be successful and at least a third in all three nations feel a solution will never be reached. Optimistic bunch. Full results here. (pdf)

(AP Photo)

Hugh White's essay on the emerging great power competition between the U.S. and China and what role Australia should play is making quite an impact in wonkish Australian circles. It's been little remarked on in the U.S. as far as I can tell, no doubt thanks to the preoccupation with Afghanistan and Iran, but it's a debate worth following closely. It's a foreshadow of the more urgent strategic debate slowing gaining ground in the United States - to wit: whether to "accommodate" China or attempt to contain and contest her rise.

Australia's position is unique, obviously. They cannot choose containment if no one else does, but Australia could undermine any potential American containment regime by unilaterally choosing accommodation. Australia, as White documents, is in a tough spot and has been ill-served by leaders who have refused to wrestle with the strategic implications of a rising China and the potential for a U.S.-China clash.

Crispin Rovere provides a good overview of the strategic debate in Australia:

It is good to remind ourselves of what the underlying beliefs were when the 'hedging' strategy was formed. These have underpinned it to the present day. The prevailing assumption being that, as China became richer, several things would occur: (a) An educated middle class would emerge, free from subsistence concerns, demanding greater political freedom and precipitate liberal democratic reforms; (b) China, after realising the benefits of export-driven growth, would see little reason to rock the boat, and gratefully integrate itself into the American led international order, just as Japan did after its post-war reconstruction; and (c) eventually one-party rule would cause stagnation in the Chinese economy, just as it had done in the Soviet Union. Ultimately the Chinese elite would see the Washington Consensus as the only viable model for a successful capitalist system, with the government removing itself from the affairs of the private sector.As of 2010, none of these things have happened. On the contrary, as the Chinese are becoming richer they are becoming more nationalistic, and the Chinese Communist Party's legitimacy is now reliant upon, rather than subverted by, sustained economic growth. China is integrating into the US-led order only in as much as it serves its perceived interest, but is taking an increasingly assertive line as their power grows. [emphasis mine]

I wonder if China's reliance on economic growth isn't much the same thing as being subverted by it. In an important sense, the Communist Party's legitimacy is now tied to the economic prosperity of its people in a way that it simply wasn't before. To the extent that China needs good relations with America and its Asian trading partners to sustain its economic growth, wouldn't the Communist leadership remain wary about upsetting the applecart?

The question, and worry, is what happens if China's economic growth unexpectedly sputters. Will the Communist party seek legitimacy in nationalism and external conflicts? Or will it dabble with political liberalization in the hopes of reviving its economic fortunes and staving off internal unrest?

(AP Photo)

Bruce Riedel argues that unless Israel is reassured by the U.S. that its nuclear deterrent remains unmatched in the region, it will attack Iran. Such an attack, he writes, would be a "disaster in the making" and so he recommends extending the U.S. nuclear umbrella over Israel and admitting them into NATO.

The purpose of the U.S. "nuclear umbrella" was to 1. protect weaker countries from a nuclear threat; 2. prevent proliferation. Neither of these applies to Israel which is stronger than Iran and already has its own, vastly superior, nuclear arsenal. If Iran is not going to be deterred by Israel's arsenal, which could, according to Anthony Cordesman, likely kill between 16 and 28 million Iranians and end Iran as a functional political entity, then they're not going to be deterred by the U.S. either. Still, you could make the case that the U.S. should nonetheless extend the nuclear umbrella to Israel as an expression of support and a further warning to Iran not to push it.

NATO admission, though, is much more problematic, not least because it's hard to envision a single Western European member country (or, um, Turkey) being enthusiastic about the prospect. NATO was formed for a specific purpose, to defend Western Europe from a Soviet attack. The borders in this instance were clear, as were the combatants. NATO offered protection to nations that were, individually, weak before a much stronger conventional enemy. None of this applies to Israel. It is the stronger party - both vis-a-vis Iran and its non-state adversaries (Hamas, Hezbollah) - its borders are unsettled, and the combatants are not fixed armies but armed guerilla groups that blend into the populace of Israel's neighbors.

Admitting Israel to NATO would open up a host of questions. How, for instance, would NATO interpret Article V of its charter which stipulates that an armed attack on one will be deemed an attack on all? The language was invoked only once in the organization's history: on 9/11. Yet Israel suffers serious terrorist attacks on a more routine basis. Would NATO be bound to attack Hamas in Gaza or Hezbollah in Lebanon? Given how NATO has performed in Afghanistan, it's difficult to see them rushing into the Levant.

According to Politico, he has a new "tell all" memoir coming out. Rumsfeld always struck me as one of the bigger curiosities of the Bush administration. Here was a person openly skeptical of nation building whose military embarked on two large episodes of just that. According to several accounts of the Iraq war, he played an unhelpful role in the post-war planning precisely because he was dismissive of nation building - which raises the question of why he would stump for a war in the first place.

That aside, I think Rumsfeld has become a convenient scapegoat for what was - and remains - a dubious set of propositions advocated by his critics. Rumsfeld's vision of military transformation was far too parsimonious for neoconservatives, who championed an American Empire and waxed nostalgic for the British Colonial Office. To the military's traditional role of defeating and deterring conventional nation states, Rumsfeld labored to add the ability to quickly locate, target and destroy terrorist cells and facilities around the globe and to accomplish these tasks remotely, minimizing U.S. casualties. Such a vision demanded a lean, agile and networked force. It was not, however, the neocolonial occupation army demanded by his critics.

Rumsfeld was clearly the odd man out in an administration that jettisoned its realist sensibilities in the aftermath of 9/11 in favor of a more ambitious use of American power. His preference to turn Iraq over to the Iraqis quickly stood in stark contrast to the administration's professed aims of constructing a democracy in the heart of the Middle East. His desire for a rapid exit undoubtedly hastened Iraq's sectarian fragmentation, but such a fragmentation was inevitable. The U.S simply did not possess enough manpower to accomplish what Rumsfeld's critics wanted to in Iraq.

Linkage - the idea that there is a direct correlation between the Mideast peace process and the successful isolation of the Islamic Republic - has been the source of much debate in recent months in pundit and policy making circles, especially as Iran has eclipsed Israel's other security concerns in the Middle East.

Arab sheikdoms and autocrats, or so the argument goes, would naturally fall in line behind any U.S.-Israeli security regime in the region, as most of these actors - once pressed on the matter behind closed doors - would readily list Iran as their top regional concern, much as the Israelis already do. There's plenty of reason to believe that such a model for isolating Iran might emerge, evidenced more recently by the goody bags of weapons systems being doled out throughout the region.

But one of the pitfalls in creating such a regional dynamic, whereby the United States essentially guarantees the security and stability of the surrounding autocrats and monarchs, is what we're witnessing this week in Bahrain and Kuwait. When America's top diplomat calls Iran an emerging Junta, and the West repeatedly calls Tehran a regional threat, it gives the region's other not-democracies - you know, the friendly ones - carte blanche to suppress and discriminate against their Shia minorities and, in the case of Bahrain, majorities.

This certainly isn't breaking news, and Iran is by no means innocent of fanning the flames of sectarian division; and Secretary Clinton is, by the way, probably correct in her assessment of the Iranian leadership. But I question whether or not pandering to what are very old ethnic and religious differences is the best way to foster a 'cold' containment in the Middle East, or if it will only backfire and solidify Iran's place as champion of the global anti-American.

(AP Photo)

I read recently that former UN Ambassador John Bolton was contemplating a presidential run, presumably on the theory that he could hammer President Obama over national security and foreign policy issues. And why not, it's a free country.

But there's some bad news in this Chicago Council on Global Affairs survey of U.S. attitudes toward foreign policy. Specifically, there's not much evidence that America supports the kind of militaristic, unilateralism espoused by Bolton. Nor, as Matt Duss points out, is there overwhelming support for military action against Iran.

Haaretz reports on a new iPhone app that will track building in the West Bank:

Settlements are symbolized by little blue houses on the map. Clicking once on the icon gives its land area. A second click brings up a window with more details: the year it was established, population, ideology (or lack of), character (secular or religious), amount of 'private Palestinian land' it occupies, and a graph that tracks its population growth.iPhone users can also zoom in on outposts marked in red. The map includes the route of the Green Line, Jerusalem's municipal boundaries, and the various zones under different security arrangements, Area A and Area B.

Via Gallup, it seems the Obama administration has made some modest strides in bolstering America's image in Asia:

Approval of U.S. leadership in Asia has seen its share of ups and downs over the last two years as the Bush era ended and the Obama era began. So far in 2010, approval ratings remain higher than they were in 2008 in 10 out of the 18 countries surveyed. Approval increased most in Australia and New Zealand and declined most in Vietnam, Indonesia, and India, where residents are now significantly more uncertain...In fact, in many other countries in the region where approval is lowest -- Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Indonesia -- about half or more of respondents do not have an opinion about U.S. leadership, but those who do are more likely to approve than disapprove. The number of respondents who express uncertainty about U.S. leadership has increased significantly since 2008 in India, Vietnam, Nepal, and Indonesia.

And where is approval for U.S. leadership the lowest? Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Via the New Statesman:

More than 9,000 public sector workers take home a higher wage than the prime minister, new research conducted by the BBC's Panorama programme has shown.The study, which collected data from 2,400 different public bodies revealed that 38,000 public employees are earning above £100,000, with 1,000 people on more than £200,000.

Arifa Akbar reports:

Mao Zedong, founder of the People's Republic of China, qualifies as the greatest mass murderer in world history, an expert who had unprecedented access to official Communist Party archives said yesterday.Speaking at The Independent Woodstock Literary Festival, Frank Dikötter, a Hong Kong-based historian, said he found that during the time that Mao was enforcing the Great Leap Forward in 1958, in an effort to catch up with the economy of the Western world, he was responsible for overseeing "one of the worst catastrophes the world has ever known".

Mr Dikötter, who has been studying Chinese rural history from 1958 to 1962, when the nation was facing a famine, compared the systematic torture, brutality, starvation and killing of Chinese peasants to the Second World War in its magnitude. At least 45 million people were worked, starved or beaten to death in China over these four years; the worldwide death toll of the Second World War was 55 million.

A staggering, incomprehensible sum.

(AP Photo)

Ever since Shibley Telhami's poll was released showing Arab support for Iran's nuclear program, analysts have been scratching their head trying to reconcile that with the conventional wisdom that the Arab world is deeply worried by an ascendant Tehran. David Pollock dives into the polling:

But since last autumn, when Obama reached a public compromise with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on the hot-button issue of Israeli settlements, a number of different polls have measured Arab attitudes toward Iran. In every case but one, these surveys have consistently demonstrated heavily negative views of Iran, its nuclear program, and of Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The mistake of Telhami, and other analysts, is to rely on a single 2010 Zogby poll to make their judgement, rather than considering the full range of polling on the issue.

(AP Photo)

By selling novel souvenirs, of course:

Two U.S. tourists unknowingly bought six human skulls in Greece, which they learned when they were stopped at the airport in Athens.The Americans carried the skulls in their hand luggage, which was scanned during a layover on their way back to the United States from the island of Mykonos.

My first thought when I saw that the Obama administration was readying a sale of F-35s to Israel on top of the multi-billion dollar arms deal with Saudi Araiba, was that Obama had finally found an economic stimulus plan that would work - another world war.

Kidding aside, I think this does mark the close of the Obama administration's "carrot" phase of Iranian diplomacy, such as it was. It's impossible now for the United States to convince Iran that it doesn't need a nuclear weapon when the U.S. is helping to massively boost other militaries in the region. From an Iranian perspective, U.S. arms sales will only reinforce the notion that they need a nuclear weapon to offset the large and growing imbalance of conventional military power in the Middle East.

The good news is that the balance of power in the Gulf is stacked overwhelmingly against the Iranian regime. It will be hard to take claims of Iranian "hegemony" seriously if more and more countries in the region belly up to the U.S. arms bar.

(AP Photo)

The United States seems on the verge of okaying the biggest arms deal in American history to the country that provided 15 of the 19 9/11 hijackers, much of the critical funding for al Qaeda and was home to Osama bin Laden. This is a sign of something more than just the passage of time or our acceptance of the manifold official statements that there was no linkage between the terrorists and the Saudi government. (After all, such arguments hardly seem necessary as we know that the hijackers were backed both by elements of the Pakistani secret service and the Taliban and these days we seem willing enough to cut deals with them or, the case of "good" Taliban, at least contemplate it.)No, the reason that the U.S. government -- that would not have done a deal like this in the years right after 9/11 -- is willing and even a little eager to move ahead with the deal now is that the War on Terror is being overtaken among top U.S. concerns by the advent of a nuclear Iran....

So while we might describe this new era a "smaller" version of the face-off with the Soviets, a Mideast Cold War or Containment 2.0, it could well be much more complex and present new challenges. In any event, it will certainly be even more dangerous than the "War on Terror" era that it is following and that -- due to the misplaced priorities it provoked from leaders like Blair and Bush -- helped contribute to this new and worrisome period of escalating risks. - David Rothkopf

It's a good point but it's worth raising the question of which is the bigger danger to Americans: al-Qaeda or a nuclear Iran. If we accept the premise that Iran is not going to launch a nuclear attack against the United States (a premise I think is fairly sound), who has the more pronounced tendency to kill American civilians? Clearly al-Qaeda. But al-Qaeda cannot pose a strategic threat to the United States while Iran could, potentially, cause the price of oil to rise.

Expensive oil could seriously impair the U.S. economy, with all the attendant human costs associated with that. But as Rothkopf suggests, containing the threat of a nuclear Iran is going to mean empowering the very regimes and reinforcing the very dynamic (U.S. support for Gulf autocrats) that help propel al-Qaeda into a global menace in the first place.

Alex Massie has a worthwhile take:

More problematically still, this kind of support for the Saudis ensures that different strands of American policy are working at cross-purposes to the point, perhaps, where different American objectives become mutually exclusive. Washington would like a totally transformed middle east; deep down it suspects this isn't possible and, anyway, nothing is so terrifying as instability and change guarantees instability so change is not a Good Thing.Admittedly, the Obama administration has dialled-back on the human rights and liberty agenda that was, at least fitfully, a part of the Bush administration's long-term, optimistic, vision for the wider Middle East. Nevertheless, Washington continues to talk a lot about values (while forgetting that the rest of the world can hear this) and then demonstrates the worth of those values by buttressing and arming disgusting regimes whose repressive policies help produce extremism and, in the end, anti-Americanism.

The US isn't simply meddling in the middle east, it supports the very people it acknowledges (at least sometimes) are a large part of the problem.

Is there a way to break this cycle?

No, really:

Amid all the furor stirred by the French government’s decision to repatriate hundreds of Romanian and Bulgarian Roma, many would be surprised to learn that Sarkozy is a pretty popular name among the Roma communities in Slovakia, Hungary, and Romania. No, not French President Nicolas Sarkozy, but the name Sarkozy -- or rather Sárközy.

Angus Reid finds skepticism in Canada on the value of immigration:

Overall, 46 per cent of respondents (+5 since August 2009) say immigration is having a negative effect in Canada, while 34 per cent (-3) believe it is having a positive effect. Albertans (56%) and Ontarians (55%) are more likely to view immigration in a negative light than respondents in all other provinces.About two-in-five Canadians (38%) believe the number of legal immigrants who are allowed to relocate in Canada should decrease. A similar proportion (39%) would keep the current levels, and 16 per cent call for more immigrants to be allowed into Canada. Ontario (42%) and Quebec (40%) hold the highest level of support for decreasing legal immigration.

A plurality of respondents (44%) think the illegal immigrants who currently reside in Canada take jobs away from Canadian workers, while a smaller proportion (38%) believe they are employed in jobs that Canadian workers do not want. More than half of Ontarians (52%) think illegal immigrants are taking jobs away from Canadians.

Almost half of Canadians (47%) believe illegal immigrants should be required to leave their jobs and be deported from Canada, while 23 per cent would allow them to stay in Canada and eventually apply for citizenship. Almost one-in-five (17%) would allow these illegal immigrants to work in Canada on a temporary basis, but would not give them a chance to become citizens.

Ontarians (53%) and Albertans (52%) hold the highest level of support for the deportation of illegal immigrants, while British Columbians are at the other end of the spectrum on this question (39%).

As the terrorism network’s Yemen branch threatens new attacks on the United States, the United States Central Command has proposed supplying Yemen with $1.2 billion in military equipment and training over the next six years, a significant escalation on a front in the campaign against terrorism, which has largely been hidden from public view.The aid would include automatic weapons, coastal patrol boats, transport planes and helicopters, as well as tools and spare parts. Training could expand to allow American logistical advisers to accompany Yemeni troops in some noncombat roles.

Opponents, though, fear American weapons could be used against political enemies of President Ali Abdullah Saleh and provoke a backlash that could further destabilize the volatile, impoverished country. - New York Times

One tendency among those who are skeptical about a counter-insurgency approach in Afghanistan is to yell "Yemen!" and hope that settles it. I'm certainly guilty of this. But those who would support more of a "counter-terrorism" approach to Afghanistan should grapple honestly with how that would work. In Yemen it appears the Obama administration is wrestling with two approaches - put a large "made in America" stamp on Yemen's military forces to make them more effective at fighting al-Qaeda (so we don't have to) or taking a less overt approach which may yield a less effective indigenous force but will also help insulate the U.S. from any blowback if the Yemeni regime uses its American tools for internal repression.

I think both approaches are better, in the long run, then the kind of massive counter-insurgency under way in Afghanistan, but I wonder if the desire to build local capacity won't inexorably lead to a much deeper U.S. involvement. After all, if some terrorist plot from Yemen does wind up succeeding, the call for America to push aside its weak local partner and take care of the problem itself will only grow louder.

The other issue, as Paul Pillar notes well, is whether America's involvement in Yemen (and elsewhere) is being driven by unrealistic expectations of perfect security:

One reason for the oversimplifying, military-heavy approach toward Yemeni terrorism is that Americans in general like to view their enemies in oversimplified terms and to favor simple, direct, forceful ways of dealing with them. Another reason is specific right now to Yemen and is related to an observation that my friend Steve Simon made in a panel discussion (in which I also participated) on Wednesday at the Potomac Institute for Policy Studies. The attempted attack of an airliner last December by the underwear bomber coming from Yemen, had the attack been successful, would have been a catastrophic political blow to the Obama administration. This effect would have reflected the way Americans expect perfection in counterterrorism, along with the partisanship that causes political opponents to pounce enthusiastically on any failure, regardless of its causes or how much it was or was not avoidable. So there is a strong impetus not only to do whatever possible to avoid another Yemen-originated attack, but also to be perceived to be doing that. This is an example of a demonstrable pursuit of perfection in securing Americans from terrorism working against well-considered adoption of policies that, while perfection is impossible to achieve, are apt to be more successful than the more demonstrable alternatives.

You couldn't find a better example of this than Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napalitano saying she couldn't "guarantee" that al-Qaeda wouldn't pull off another terrorist attack. But why on Earth would we expect her to make such a guarantee in the first place?

The Lede reports that Pakistan's former president is contemplating a comeback. Probably just what the embattled country does not need at the moment.

If you have a few minutes it's worth checking out this panel discussion the New America Foundation hosted on the war in Afghanistan. The first talk by Michael Waltz is particularly good at arguing for a counter-insurgency strategy. But, as usually happens when I hear someone explain why a more narrow counter-terrorism strategy won't work in Afghanistan, Waltz never really fleshes out what COIN is supposed to deliver on the terrorism front. For instance, no COIN advocate can really claim that successfully tamping down the Taliban insurgency inside Afghanistan is going to route al-Qaeda fighters from inside Pakistan or, more importantly, have any impact on al-Qaeda's presence in Yemen or around the world.

This basic dynamic is what makes folks skeptical about counter-insurgency. It's not that, given adequate time and resources, it won't work. It might work. But that even if it does work, we're still going to have a serious, insidious global terror threat. And given that the U.S. doesn't have an infinite amount of money, time and manpower it can devote to Afghanistan, we need to think about the country in the context of a broader threat.

They like him:

A sizeable proportion of people in Britain maintain a positive opinion of Winston Churchill and two thirds believe that Gordon Brown has been the worst head of government since the end of the Second World War, a new Angus Reid Public Opinion poll has found....Four-in-five Britons (79%) describe Churchill as a good prime minister. No other British head of government reaches the 50 per cent mark on this indicator, with Margaret Thatcher (47%), Tony Blair (39%), Harold Wilson (37%), David Cameron (34%), and Harold Macmillan (31%) getting a good review from at least three-in-ten respondents.

Churchill's overall score of +75 (a comparison between positive and negative responses) is the best for all 13 heads of government featured in the study. Only three other prime ministers posted a positive rating: Wilson (+16), Clement Atlee (+15) and Cameron (+7). In stark contrast, Gordon Brown (-45) and John Major (-25) had the lowest scores.

See the full survey here. The Financial Times took a more elite survey on British prime ministers here.

Dov Zakheim comments on the news that a Saudi diplomat has sought asylum in the U.S because he's gay and, apparently, had a relationship with a Jewish woman. That's 0-2 in the Kingdom and, apparently, could cost the diplomat his life. This prompts Zakheim to write:

Since the onset of the Cold War, and, more recently, in the seemingly endless war on terrorism (or whatever euphemism is employed for the conflict with Islamic extremists), the United States has consistently given higher priority to its national security and economic interests than to the human rights and freedoms that it holds dear. This policy, which, with a few periodic exceptions, has been bipartisan for over a half century, invariably outrages those on the Left, who in any event have little sympathy for U.S. security or economic policies.Most policymakers recognize the dilemma they face: yet, like Winston Churchill, who hated Communists but was prepared to ally himself with Stalin to defeat Hitler, they accept that circumstances will dictate whether, and for how long, one must, in Churchill's famous term, "sleep with the devil."

Two things to note about this. It's not just the left that expresses unhappiness with this arrangement. Zakheim's former boss did too. As noted below, it was conservatives during the Bush-era who took up the mantra that freedom in the Middle East was the only surefire antidote to terrorism.

The other issue is the question of necessity. The example Zakheim invokes as justification for America holding its nose and sleeping with the devil was rather extreme. The Cold War had its own exigencies and Saudi Arabia did prove to be a useful ally as well. But the Cold War is over and the 9/11 attacks revealed a much darker side to America's strategic partnership with Saudi Arabia.