Putin, Beastmaster

(AP Photo)

« March 2010 | Blog Home Page | May 2010 »

(AP Photo)

The more I think about it, the more it seems as though countries like Iran play and manipulate the United Nations like the southern Democrats manipulated the American Senate throughout the 20th Century. Here's yet another example:

Without fanfare, the United Nations this week elected Iran to its Commission on the Status of Women, handing a four-year seat on the influential human rights body to a theocratic state in which stoning is enshrined in law and lashings are required for women judged "immodest."

Buried 2,000 words deep in a U.N. press release distributed Wednesday on the filling of "vacancies in subsidiary bodies," was the stark announcement: Iran, along with representatives from 10 other nations, was "elected by acclamation," meaning that no open vote was requested or required by any member states — including the United States.

The primary offense here seems to be bureaucratic indifference, which is understandable, since this nomination appears to have been Iran's fallback option once the regime realized it wouldn't get on the equally dubious Human Rights Council.

The Obama administration never should've changed the Bush policy on that body, but I think the best response to this latest silliness is none at all.

(AP Photo)

Dan Blumethal has a thorough post examining the implications of China's growing naval strength and what America's response should be:

Taiwan's importance is the same as the importance of our Japanese, South Korean, and Philippine allies -- more geopolitical than geostrategic. These countries have embraced the international system that the United States created and defended after World War II. They are democratic states with free market economies that all want to be part of what used to be called the "West," the worldwide club of modern, advanced industrial democracies. Washington's interests are better served when economically vibrant democracies are free from the control of other great powers - this better ensures that the international system remains hospitable to us.In my opinion, for geopolitical as well as geostrategic reasons, the United States military should maintain a (more defendable) presence on the territory of as many U.S. Asian allies as welcome it, at least until all can be assured that China will be a responsible and democratic great power, uninterested in creating its own exclusive economic or military spheres. That means we need to work harder to help our allies build capabilities that help frustrate China's military plans rather than pulling back and relying mostly on offshore bases.

To rephrase this, Blumenthal thinks we should engage in a massive Asian arms race until:

*China is "responsible"

*China is "democratic"

*China does not want "exclusive economic or military spheres"

Of all these conditions only one - a closed economic sphere - strikes me as something worth attempting to stop. I have no idea what being "responsible" means in this context but if it's a proxy for "doing what Washington says to do" then good luck with that. As for democratic, that's irrelevant. If China doesn't want to wage war on her neighbors or carve out exclusive economic zones in which we can't participate it, that should be enough for American policy.

As for a "military sphere" this is another way of saying that America must be the strongest military power in Asia (i.e. that it remains an "American sphere"). Such a strategy is plausible if we're counting the aggregate power of our allies and, crucially, we're not trying to sustain a similar posture everywhere else. Otherwise we're just going to accelerate our own bankruptcy and decline.

Finally, there is the idea that China will want to create a "closed" economic zone - precisely where and how this would occur and what material impact it would have on the U.S. isn't really specified, but isn't this rather important to spell out? It's been noted before but China is only growing powerful because it is participating in the open international economy (including trade with the U.S.).

Still, I think it's only proper to look 20 years down the road and hedge against the possibility that China, having grown strong off the system, would seek to fundamentally upend it. But it would be nice if advocates of a "preemptive containment" of China could state the case a bit more concretely.

(AP Photo)

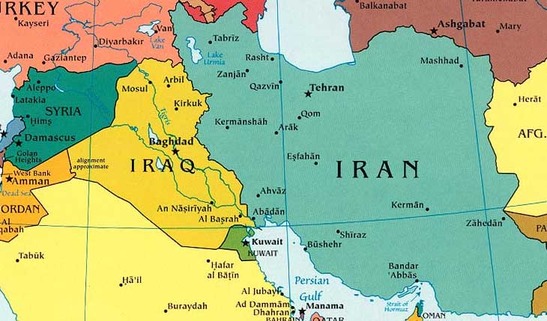

One of the very legitimate concerns about Iran acquiring nuclear capability is that it would spur other states in the region to acquire their own nuclear weapons as a deterrent. There's some reason to doubt this would happen - Israel fought actual wars with many Arab states and acquired a nuclear arsenal decades ago without causing a cascade of proliferation. But nevertheless non-proliferation experts think it's a very real possibility (and indeed some believe an arms race has more or less already begun).

But now Evelyn Gordon raises the opposite worry: that Arab states, including Saudi Arabia, will jump into Iran's orbit:

The prospect of a shift in Saudi Arabia’s allegiance ought to alarm even the Obama administration. Saudi Arabia is not only one of America’s main oil suppliers; it’s also the country Washington relies on to keep world oil markets stable — both by restraining fellow OPEC members from radical production cuts and by upping its own production to compensate for temporary shortfalls elsewhere.Granted, Riyadh is motivated partly by self-interest: unlike some of its OPEC colleagues, it understands that keeping oil prices too high for too long would do more to spur alternative-energy development than any amount of global-warming hysteria. And since its economy depends on oil exports, encouraging alternative energy is the last thing it wants to do.

Nevertheless, the fact remains that Saudi Arabia has been generally effective as stabilizer-in-chief of world oil markets and has no plausible replacement in this role. And since the U.S. economy remains highly oil-dependent, a Saudi shift into Iran’s camp would effectively put America’s economy at the mercy of the mullahs in Tehran.

So Iran would replace America's role as Saudi Arabia's close ally and use that position to... do what exactly, convince OPEC to raise the price of oil to $200 or $300 a barrel? It's possible that the Saudis could be that monumentally stupid as to put their entire economy (and monarchy) on a path to extinction, but even Gordon seems to doubt it.

Still, one could imagine a possible upside here. If Iran took the Saudi royal family under its wing, than perhaps bin Laden & co. would direct their fire at Tehran.

(AP Photo)

The Heritage Foundation recently hosted an interesting event on "The Dollar, The Euro, and the International Monetary Order" with, among others, Nobel Prize-winning economist Prof. Robert Mundell (described by Heritage as "the academic founder of supply side economics"). NRO's Sean Rushton gives a nice rundown of Mundell's quite impressive bio here:

For those not familiar with the Nobel Laureate, Mundell has been a guiding force behind major economic expansions since the early 1960s. His work as a young man likely influenced the Kennedy administration to ignore its Keynesian advisers in favor of tax cuts and sound money, leading to the robust expansion of 1961–68. Mundell correctly predicted the inflationary disease of the 1970s and advocated the supply-side policy mix that spurred two decades of non-inflationary expansion in the 1980s and ’90s. Mundell’s writing on optimum currency areas was the basis for the euro’s creation in 1999, erasing exchange-rate barriers across the world’s second largest economy. And Mundell has been an important adviser to China for two decades, guiding its economy out of Communist infancy to become the significant financial power it is today.The full video of the event is below, and Mundell's remarks start at about 1:15. For those of you who don't have the time to watch, Rushton also helpfully summarizes most of Mundell's comments (emphasis mine):

Mundell argues the recent crisis had three distinct parts.Part One was the real-estate bubble and subsequent bank-solvency crisis, which began in 2006. He says the bubble was generated primarily by the dollar’s fall after 2001, as U.S. monetary authorities made clear they wanted a lower dollar to improve exports. As the greenback dropped on foreign exchanges and against gold and other commodities, investors pursued the classic inflation hedge: They borrowed and bought hard assets, expecting to repay the debt with cheaper future dollars. Real estate, already roaring due to 1997’s expanded housing tax deduction, went into overdrive, goosed by subprime lending and mortgage securitization.

Part Two of Mundell’s analysis is the most intriguing and least understood aspect. He argues that, as the real-estate bubble burst, large quantities of fresh liquidity were demanded by the public and banks. In summer 2007, the world’s central banks supplied it and no liquidity crunch developed. But by summer 2008, spooked by rising inflation, the U.S. Federal Reserve failed to provide adequate cash, leading to dollar scarcity. Four key symptoms of tight money appeared within months: the dollar rose 30 percent against the euro; gold fell 30 percent; oil fell 80 percent; and the inflation rate dropped from 5.5 percent to negative levels. As a result, Mundell believes, Lehman Brothers collapsed, the stock market went into free fall, and a near-panic ensued. This phase was entirely preventable and constitutes one of the worst mistakes in Fed history, Mundell says. The crisis eased in early 2009, as the Fed upped the money supply, but the damage was done.

Part Three of Mundell’s analysis is the recession of 2008–09, with bailouts, rising unemployment, and skyrocketing deficits. He predicts decent growth this year, but believes unemployment will remain high and the recovery will be weak.

He says the U.S. must extend the Bush tax cuts and should also cut the corporation tax rate from 35 percent to 15 percent, to spur investment and recapitalize banks. Importantly, he says the U.S. should fix the dollar’s value against the yuan and the euro, thus creating an enormous common-currency area free of exchange-rate turbulence, which will prevent future debacles. It should be clear that Mundell sees a low and unstable dollar as culprit Number One in the crisis, and as the Bush administration’s biggest mistake.

The statements excerpted by Rushton above are also important, as they demonstrate Mundell's firm beliefs that (i) one of, if not the, biggest cause of the financial crisis was the significant US dollar devaluation undertaken by the Bush administration to improve American exports' global competitiveness; and (ii) the surest course to preventing future global meltdowns is pegging the US dollar, the Euro and the Chinese yuan (or RMB) and maintaining a strong, stable dollar.

So to summarize, Nobel Laureate, "father of supply-side economics," and presidential/Chinese economic adviser Robert Mundell is of the strong belief that (a) domestic price stability, not international export advantage, is China's primary reason for its historic RMB peg to the U.S. dollar; (b) pursuing an export-driven weak dollar policy was and will be disastrous for the U.S. economy; and (c) a fixed USD-RMB-EUR system would improve global trade and is the best way to prevent another collapse.

Now, I'm certainly not qualified to agree or disagree with Mundell's currency theories, but that's (once again) not my point. Instead, it's more important for me to just keep showing all of the serious and divergent ideas out there about global currency issues, particularly those from well-respected currency gurus showing very sound and sensible reasons for China's currency policies - ones that have nothing to do with conspiratorial allegations of predatory Chinese trade policies or breathless (and dangerous) demands that China appreciate the RMB. These "other" ideas deserve wide circulation because they are a vital counterweight to the current demagoguery out there in the U.S.-China currency debate. When guys like Mundell speak up, whether you agree with them or not, they further undermine the ridiculous certitude of American currency hawks like Paul Krugman and Sen. Chuck Schumer that China is intentionally manipulating its currency in order to prey on US industries and steal American jobs, and that some sort of dramatic RMB appreciation (and weaker US dollar) will magically solve the US and global economic crisis.

And the lesson, as always, is: when someone tells you with utter certainty that China is through its currency policies preying on the American worker, or that a stronger Chinese yuan and weaker US dollar will definitely improve the American economy, just stop listening.

This sounds about right:

Mervyn King, the governor of the Bank of England, has privately warned that whichever leader wins the election next week will be kicked out of power for decades because of the severity of budget cuts they will have to instigate, it was claimed today.As the leaders of the three main political parties prepare themselves for tonight's final, economy-themed TV debate in Birmingham, the warning ringing in their ears is that the job of Prime Minister could be a poisoned chalice.

Meanwhile, the Economist writes of the candidate's whistling past the financial graveyard:

In 2008, just before the fall of Lehman Brothers, Alistair Darling, the chancellor of the exchequer, let slip the prediction (controversial at the time) that Britain was in for the worst recession in sixty years. Two years, one semi-nationalised banking system and six quarters of painful contraction later, he has been proved right. The government deficit is 11.6% of GDP. Public debt is forecast to peak at £1.4 trillion (around 75% of GDP) in 2014-15 (a figure that ignores public-sector pension liabilities). Big spending cuts and tax rises will be needed to restore order to the public finances. Yet the looming age of austerity has figured only fitfully in a campaign that has so far been dominated by the unexpected rise of the Liberal Democrats.

Stephen Walt reads Aaron David Miller's essay on junking the peace process and asks a question similar to the one that I posed earlier in the week: if there's no peace process, how is Israel ultimately going to deal with the Palestinians? Walt, and indeed most peace process devotees, operate under the assumption that as there are increasingly more Palestinians under Israeli control it will be correspondingly more difficult for Israel to remain both Jewish and democratic and, crucially, that it will be correspondingly more difficult for the U.S. to support Israel under those conditions.

As Walt sees it, there are three possible scenarios:

So here's the question I'd really like Miller to address: if it becomes clear that "two states for two peoples" is no longer an option, what does he think U.S. policy should be? Should we then favor the ethnic cleansing of several million Palestinian Arabs from their ancestral homes, so that Israel can remain a democratic and Jewish state? (By the way, that would be a crime against humanity by any standard.) Or should we then press Israel to grant the Palestinians full political rights, consistent with America's own "melting-pot" traditions? (That is the end of the Zionist vision, and may be unworkable for other reasons). Or should we back (and subsidize) their confinement in a few disconnected enclaves (in Gaza, around Ramallah, and one or two other areas in the West Bank), with Israel controlling the borders, airspace, and water resources? (This is the apartheid solution, and it's where we are headed now.) I fear that some future president will have to choose between these three options, and it would be interesting to know what an experienced Middle East negotiator like Miller would advise him or her to do then.

I don't think that these are the only options available (and the framing of them puts all of the onus on Israel when there are other actors in this drama) but for the sake of argument let's assume Walt's got the bases covered. Why does he assume that any of these outcomes would provoke some kind of crisis in Israeli-U.S. relations or even present a problem for a future U.S. president and his/her foreign policy?

In any of the above scenarios, Israel will justify its behavior as being consistent with its core security interests. Israel's defenders will - quite rightly - argue that the U.S. supports regimes with far, far worse records when it comes to populations under their protection. If our support of Israel is paying real strategic dividends with respect to U.S. security, as some claim, then is it really a big deal how they treat the Palestinians?

In all of Walt's various scenarios, the people and NGOs who are concerned with the living conditions of the Palestinians will continue to call attention to their plight. And the people who currently don't care, or who believe that the Palestinians have brought it on themselves, or believe our support for Israel is mandated by God, or by our own security interests, will likely continue to put those considerations ahead of statehood for the Palestinians.

(AP Photo)

Hold on to your laptops, Hugo Chavez has given birth to his first tweet:

Loosely translated, it means,

How you doin'? Appeared as I said: at midnight. Headin' to Brazil. And very happy to work for Venezuela. We'll triumph!

Chavez's latest public relations effort is, according to his Minister of Public Works, Diosdado Cabello (whose name means God given hair), due to the opposition's active use of Twitter to protest and ridicule the Venezuelan president:

"The opposition thinks it owns the social networks. They think Twitter and Facebook are theirs. We are taking the battle to them, and we are 7 million militants that will take Twitter."

Of course, three months ago Chavez himself was declaring that

"using Twitter, the Internet (and) text messaging" to criticize or oppose his increasingly authoritarian regime "is terrorism."

Can't wait for the "seven million militants" to "take Twitter", now that Hugo's in.

Fausta Wertz blogs at Fausta's blog.

This one's a nightmare for anyone planning adequate and robust homeland security defenses - Reuters reports from Moscow that a Russian company is marketing a new cruise missile system which can be hidden inside a regular shipping container, potentially giving any merchant vessel the capability to wipe out an aircraft carrier.

The Club-K was put on the market at the Defense Services Asia exhibition in Malaysia for $15 million. At the exhibition, the marketing film showed the Club-K being activated from an ordinary truck and from an ordinary merchant vessel. The missiles, which have a range of 350 km (approx. 210 miles), are launched without further preparation and are targeting what looks like American ground and sea-based forces.

Defense analysts say that potential customers for the Club-K system include Iran and Venezuela – and, potentially, terrorist groups. Reuters quotes Robert Hewson of Jane’s Defense Weekly to say that “at a stroke, the Club-K gives a long-range precision strike capability to ordinary vehicles that can be moved to almost any place on earth without attracting attention. The idea that you can hide a missile system in a box and drive it around without anyone knowing is pretty new,” said Hewson, who is editor of Jane’s Air-Launched Weapons. “Nobody’s ever done that before.”

Hewson estimated the cost of the Club-K system, which packs four ground or sea-launched cruise missiles into a standard 40-foot shipping container, at $10-20 million.

“Unless sales are very tightly controlled, there is a danger that it could end up in the wrong hands,” he said.

Now with video:

Andrew Sullivan adds:

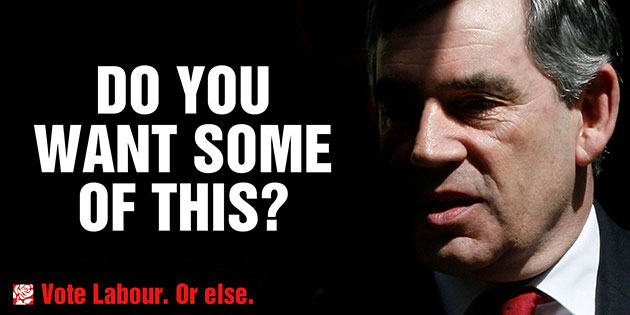

Now, with Labour in third place already, what will the millions of voters like Duffy do? Vote Tory? I'd like to think so. Maybe immigration will push her to Cameron. But Duffy's obvious belief in the classic Labour welfare state makes me suspect she could protest Labour by voting for the Liberal Democrats. Her initial response is that she won't vote at all - another disaster if replicated for Labour. If millions of Labour voters switch to the Lib-Dems, or stay at home in protest, we are talking about an electoral earthquake of historic proportions. This may be the sound that sets off the avalanche.

It should be interesting to see how this gaffe affects the daily tracking polls.

Yves Smith thinks so:

The real risk here is to Eurobanks. They ran with even higher leverage ratios than US banks, they are believed to have recognized less of the losses thus far on their books than their US peers. Even worse, readers report that the major dealers (and the Eurobanks were part of this cohort) are carrying toxic assets at prices that are vastly above likely long-term value. Eurobank exposure to Greece is over $190 billion, and total periphery country exposure is roughly $900 billion.In the subprime crisis, many pundits and the Fed itself thought the losses would be contained, unaware that for every $1 in BBB subprime bonds, another $10 in CDS had been written, and that many of these exposures sat with highly levered firms, namely insurers and dealers, who were not able to take much in the way of losses. The gross level of exposures looks much worse here and the banks most at risk have not done much (save take government handouts) to rebuild their balance sheets.

So the whole idea that the financial crisis was over is being called into doubt. Recall that the Great Depression nadir was the sovereign debt default phase. And the EU’s erratic responses (obvious hesitancy followed by finesses rather than decisive responses) is going to prove even more detrimental as the Club Med crisis grinds on.

Meanwhile, today is the third and final UK debate. Iain Martin thinks the collapsing Euro could boost Cameron:

But Mr. Cameron has just been dealt a potential ace by the markets. It will be interesting to see if he realizes this and works out a way of playing it in a manner that voters understand.The worsening crisis in the euro zone has attracted very little attention in the general election, thus far. After all, the U.K. isn't a member.

However, the growing crisis is at root about large debts and the markets demanding that states start taking serious action. When Mr. Brown says that there is no imperative to makes cuts, Mr. Cameron can point to what is going on in the euro zone and say with some force that here is a clear warning from next door. Britain isn't yet in line for the ire of investors; it might be sooner than one thinks if action isn't taken this day.

Meanwhile, Mr. Clegg wants to join the euro—putting him in an interesting position Thursday night.

Danielle Pletka, writing - as usual - about freedomy stuff, bemoans the president's failure to take North Korea seriously . . . or something:

This is North Korea Freedom Week (being commemorated in Seoul, Republic of Korea), though it would be hard to tell in the capital of the freedom-loving world. North Korea appears to have slipped entirely off the radar of the Obama administration; neither the plight of its downtrodden citizens nor the proliferation of its nuclear weapons technology and missiles has stirred the interest of an administration purportedly obsessed with nonproliferation.

North Korea has long had its own people, as well as our allies in Japan and South Korea, in its gun sights. With Iran’s help, our allies in the Middle East and, with time, Europe and the United States, will join that unlucky group.

I really don't want to devote too much time to this, as we already know to take Ms. Pletka's web musings with a grain of salt. So I'll simply ask: What more should President Obama be doing about North Korean oppression and proliferation?

Last year, Pyongyang threatened to test a long-range missile in the direction of Hawaii and the administration quickly moved to fortify Hawaii. Of course, North Korea's track record for testing long-range missiles has been mixed at best, so just how serious these temper tantrums should be taken is debatable.

The ability to use these weapons of course matters, but, like in the case of Iran, such details are a tangential nuisance to Pletka and other neoconservative think tankers. Obama made the necessary maneuverings to defend the country, while quietly deferring to South Korean leadership on nuclear proliferation on the peninsula. South Korean President Lee Myung-bak has taken a hard line with the North, one President Obama agrees with. This policy makes sense, as it's in South Korea's more immediate interest - as well as the entire region's - to engage and, if necessary, contain the North.

Pyongyang uses America's presence in the region as justification for its nuclear adventurism; the louder and larger the role played in the region by the U.S., the smaller and less relevant the other actors become. The Obama administration, opting to break this pattern, has stepped back and handed the leadership reins to regional actors in an effort to change the Washington-Pyongyang dynamic. (Dear Leader has apparently taken notice of this shift, and may be rattling the saber a bit louder in order to draw Washington back in.)

So I ask again: With security measures in place, nuclear know-how controls underway and South Korea in the lead, what then should the Obama administration do about North Korea?

UPDATE:

Bruce Klinger of the Heritage Foundation makes a good point, and explains why South Korean leadership - and American compliance - is even more important now in light of the Cheonan sinking:

South Korea will contemplate both unilateral actions, including punitive economic and diplomatic measures, as well as taking the issue to the UN Security Council for multilateral response. In the latter case, Seoul would face stiff opposition from China and Russia, which have obstructed previous attempts to punish Pyongyang for violating UN resolutions.If South Korea is reluctant to attack, it would be impossible for the US to be “more Korean than the Koreans” by advocating stronger measures. But the Obama administration should consult closely with the South Koreans and support whatever action they are comfortable taking. This should include pressing the Chinese and Russians to relent in favor of tougher international sanctions, and taking unilateral punitive action that complements the South Korean approach.

(AP Photo)

This probably wont' help Mr. Brown's poll standing:

The Prime Minister was heard describing an exchange he had with a female voter on the campaign trail today as a "disaster", calling her a "bigoted woman".The comments were made as he got into his car after speaking to the woman in Rochdale, not realising that he had a Sky News microphone pinned to his shirt.

He told an aide: "That was a disaster - they should never have put me with that woman. Whose idea was that? It's just ridiculous..."

Asked what she had said, he replied: "Everything, she was just a bigoted woman."

The voter, 65 year old Gillian Duffy, had pressed the prime minister on immigration and other matters.

UPDATE: Audio here.

The Washington Post reports on post-election Iraqi politics:

Sunnis, who won meager representation in the 2005 parliamentary election, voted in droves this year, contributing to Iraqiya's narrow lead. Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki's slate won two fewer seats, but could conceivably come up on top as a result of the manual recount of 2.4 million votes in Baghdad and the disqualification of elected Iraqiya candidates.That would almost certainly spark widespread anger in Sunni communities, where many view Maliki as a sectarian, and an increasingly authoritarian statesman.

The prime minister and other Shiite leaders have called the recent challenges to the election results lawful processes that must run their course. Allawi said Wednesday's statement would be Iraqiya's final appeal for fairness. He ominously warned that the party would henceforth "revert to the Iraqi people to implement their will."

Adding to the political tension, Human Rights Watch released a report late Tuesday saying that members of a military unit under Maliki's command systemically tortured and sexually abused hundreds of Sunni Arab prisoners.

The report, drawn from interviews this week with 42 men who were formally held at the Muthana Airport military base, says guards beat, shocked and sodomized inmates in an effort to get them to confess to crimes.

Part of me thinks that we've entered into a period similar to 2004-2005, where brewing trouble inside Iraq is either dismissed or ignored. Just as conservatives and the Bush administration pooh-poohed the insurgency right up until the point that it exploded, now (if they're even paying attention) they're dismissing the political violence and declaring President Bush a world-historical figure for the Surge. Liberals, who had an incentive during the Bush years to sound the alarm, have mostly fallen silent (except for Robert Dreyfuss, who thinks Iran has already won). I sure hope I'm wrong. But sectarian torture camps don't bode well for the future of a democratic Iraq.

There's a debate swirling in wonkish circles about the status of U.S. missile defenses under the New START arms control treaty between the U.S. and Russia. Critics of the deal say the Obama administration had to neuter our missile defense plans to get an agreement, while supporters of the deal say no such snipping occurred.

Dimitri Simes, writing in Time, said the Obama administration did indeed give up the store to get the arms deal signed:

Russian experts and officials... believe that America made a tacit commitment not to develop an extended strategic missile defense. As a senior Russian official said to me, "I can't quote you unequivocal language from President Obama or Secretary Clinton in conversations with us that there would be no strategic missile defenses in Europe, but everything that was said to us amounts to this." In this official's account, the full spectrum of U.S. officials from the President to working-level negotiators clearly conveyed that the reason they rejected more explicit restrictions on missile defense was not because of U.S. plans, but because of fear that such a deal could not win Senate ratification. A senior U.S. official intimately familiar with the talks has confirmed that the Russians were advised not to press further on missile defenses because the Administration had no intention to proceed with anything that would truly concern Moscow.

Arms control expert Jeffrey Lewis reads the treaty and offers his take:

I think it is very hard to conclude that the treaty “limits” missile defenses. The treaty may have some implications for missile defense programs, but on the whole it is written in such a way as to create space for current and planned missile defense programs, including language that exempts interceptors from the definition of an ICBM and the provision to “grandfather” the converted silos at Vandenberg.

I can't parse the nuances of arms control arcana, but Simes' account of the negotiations recalls the ambiguity of supposed U.S. promises* to Russia regarding NATO expansion at the end of the Cold War. That's been a persistent sore point in U.S.-Russian ties. Will this become another?

*Mark Kramer has a definitive rebuttal of Russian claims that they were promised anything with respect to NATO expansion.

(AP Photo)

Felix Samon passes along some informed speculation as to what will happen if Germany (as expected) refuses to bail out Greece. In a word, default:

Where would Greek debt trade in the event of a default? This is the scariest thing: my highly plugged-in companions both agreed that it wouldn’t just fall to 70 or even 60 cents on the dollar: they saw fair value closer to 40, and said that it would probably fall to 30 before people started buying.Needless to say, if Greek debt was trading at 30 cents on the dollar, it wouldn’t take long for the Portuguese domino to topple. After that, Spain — and then, it’s easy to imagine, Italy, Ireland, UK. And so the stakes are very high: it’s certainly cheaper to bail out Greece with virtually unlimited funds than it is to risk a fully-blown PIIGS default. But there does seem to be the hope or expectation that a line could get drawn in the Iberian sand, and that Italy and Ireland would not be allowed to default even if Portugal and/or Spain imploded.

Meanwhile, Walter Russell Mead urges us not to gloat over Europe's implosion. Sage advice. America may enjoy a short term boost as investors flee Europe, but we still need to get our own fiscal house in order.

(AP Photo)

Angus Reid has found an interesting divergence:

People in three countries hold differing views on climate change, according to a poll by Angus Reid Public Opinion. 58 per cent of respondents in Canada believe global warming is a fact and is mostly caused by emissions from vehicles and industrial facilities, but only 41 per cent of Americans and 38 per cent of Britons concur.

Moreover, more British believe that climate change is a theory that hasn't been proven yet than Americans.

I'm surprised by the UK findings given that the three leading candidates for Prime Minister have all sought to emphasis their green bona fides. Complete poll here (pdf).

The fundamental incongruity in the administration's approach is that they are banking on this Iranian government to save us from having to do the unpleasant and unpopular work of making the world a safer place. - Kori Schake

Here's another incongruity to ponder - why would making the "world" safe from Iran make the United States unpopular? Seems like a surefire winner to me.

And why - if we are indeed acting on behalf of "the world" - do large swathes of it not share our concern or embrace our preferred policy response? Could it be that stopping Iran's nuclear program is actually a more parochial interest?

This story is perfect for Hollywood - or better yet, Bollywood - screenwriters: a high-ranking Indian Commodore is embroiled in a Russian honeypot scheme that has created quite a stir in both countries.

According to British newspaper The Daily Telegraph, an Indian Commodore (First Rank Captain), tempted by a Russian woman translator in Severodvinsk, is suspected of inflating the price of the aircraft carrier "Admiral Gorshkov," which India bought from Russia. Commodore Suhdzhinder Singh led one of the Indian delegations that monitored the repair work on heavy aircraft carrier "Gorshkov" in the northern Russian city of Severodvinsk in 2005-2007. It was then that he met with an attractive blonde interpreter Masha.

"They met so closely that their photos are now studied very closely at the Ministry of Defence of India," writes Komsomolskaya Pravda. It is not known how these photos came into the hands of the Indian military, but there is now an official investigation against the Commodore.

The Daily Telegraph writes that the Indian officer was so influenced by his Russian girlfriend, that he "overestimated" the value of the work on the aircraft carrier. The original contract of purchase for "Admiral Gorshkov" was around $1 billion, but in the end, after much bilateral arguments with Russian counterparts, New Delhi agreed to pay almost $2.3 billion. The paper put the blame for this debacle on the Russian intelligence.

Commodore Singh, one of the leaders of the aircraft repair and refurbishment monitoring team, arrived in Russia in early October 2004. Specialty Engineer by profession, with 25 years of immaculate service in the Navy, married with two children - he exemplified an "ideal officer" in his country.

He lived away from his family for six months - his wife and kids remained in India. "Logically, local Russian beauties turned their attention to the dashing Indian officer," writes Komsomolskaya Pravda. "The women of Severodvinsk dubbed foreign guest "Captain Nemo," who was often seen in local cafes and bars."

"He was very friendly," say frequenters of local hot spots. "And he enjoyed special attention amongst women. He went everywhere in his turban, which was seen as very exotic."

In December 2004, the first Indian monitoring team led by Singh met with local officials. When officials asked his team on their quality of life in Severodvinsk, Singh answered honestly: "Since we will live here for a while, we would like to integrate into this society, and be part of the local population." Russian officials then offered assistance in solving this problem.

Perhaps it was during this time the commodore was introduced to the beautiful blonde, who played such a fatal role in his career. Still, none of the inhabitants of Severodvinsk can identify the girl in the scandalous photo - they say "what a nice Masha, but is certainly not one of ours ..."

Israeli Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Daniel Ayalon will be answering questions about U.S.-Israeli relations and the future of the peace process in a Foreign Affairs web-event. RealClearWorld readers can submit a question for consideration by emailing it to us with "FA Question" in the subject line. We'll select the best and send them to Foreign Affairs.

Newsweek interviews Norway's Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg on how the country weathered the Great Recession with an unemployment rate of 3.3 percent. The secret to the country's success is, obviously, its huge oil and gas reserves in the North Sea. But the country has plowed the profits from its oil sales into a sovereign wealth fund worth $450 billion. Says Stoltenberg:

We have the most transparent and most predictable investment fund in the world. The reason we have this sovereign fund is we have saved most of the oil revenues rather than spend them on tax cuts. Our value-added tax is 25 percent and gasoline price is $8 per gallon. The whole idea is to replace our national wealth from oil and gas in the ground to equity and bonds in the international market. It has been important for the Norwegian government to avoid Dutch disease by not spending too much.

Could U.S. leaders be similarly responsible? I somehow doubt it.

There have been a spat of stories detailing the growing power and assertiveness of China's navy and the natural question of whether this portends a kind of great power clash with the U.S. in the not-so-distant future.

Abe Denmark writes in Wired about the modernization and "aggression" of the Chinese navy in the South China Sea. At the Federation of American Scientists' blog, Hans M. Kristensen discovers a new Chinese naval demagnetization facility for its submarine fleet, proof of the country's growing capability. Meanwhile, Stephen Walt draws a comparison between China's increasing regional assertive and the Monroe Doctrine. As a growing China pursues the natural course for a budding great power in expanding its influence, Walt argues, security competition with the U.S. is inevitable.

I'd say that sounds right, but Hugh de Santis reminds us that China's neighborhood is far less accommodating to a great power rise than the Western Hemisphere was to the U.S.:

Although China’s neighbors have prospered from its economic rise, they are having second thoughts about its intentions. As Asian production networks become more integrated, members of ASEAN (the Association of Southeast Asian Nations) that warmed to the idea of the China-ASEAN Free Trade Agreement when it was proposed in 2001 are beginning to worry that they will be reduced to economic appendages of Beijing.This is especially true of Thailand and Malaysia, whose exports must compete with similar and often cheaper goods from China. But even countries rich in commodities that China covets are voicing concerns, including those in mainland Southeast Asia. Chinese plans to mine bauxite in Vietnam have provoked considerable domestic criticism. Cambodia too is wary that Beijing will eventually acquire their land and water rights. Though it relies on China for money and arms, the military junta in Burma is also hedging its bets by increasing contacts with India and the United States. And Indonesia, a major beneficiary of Beijing’s ravenous demand for raw materials, has gone so far as to delay implementation of the FTA because it fears that it may put pay to its steel and textile industries.

More than its economic penetration of the region, it is China’s growing self-confidence and muscle-flexing that has aroused fears in its neighbors that its ultimate objective may be hegemony rather than harmony.

I ultimately think China's neighborhood will act as the best check on any "hegemonic" ambitions the country might harbor.

(AP Photo)

A poll in the Israeli paper Yisrael Hayom provides further evidence of the ill will between the Obama administration and Israeli public. The key findings:

What do you think of the American demand to freeze construction in Jerusalem? Support 21.8% Oppose 71.6% Don’t know/refuse reply 6.6%Who is responsible for the tension between the USA and Israel – Obama or Netanyahu?

Obama 58.6% Netanyahu 16.2% Both 17.6% Don’t know/refuse reply 7.6%Is Obama interested in improving relations with the Arab states at the expense of Israel?

Yes 60.9% No 26.5% Don’t know/refuse reply 12.6%

According to Laura Rozen, the administration is knee deep into a charm offensive directed at Israeli leaders. [Hat tip: Commentary]

Airspace Rebooted from ItoWorld on Vimeo.

This video visualizes European air travel during and after the giant ash cloud. Very neat. [Via Passport]

In international institutions, China scored big diplomatic points this weekend.

Interestingly enough, while this is ostensibly a move motivated by economics, Robert Zoellick uses words more closely associated with power politics, like "polarity," than with political economy.

For more videos on topics from around the world, check out the Real Clear World videos page.

Nile Gardiner compiles a list of the Obama administration's "top ten insults to Israel." Your mileage may vary here but Number 2 struck me as a bit curious:

In contrast to its very public humiliation of close ally Israel, the Obama administration has gone out of its way to establish a better relationship with the genocidal regime of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, which continues to threaten Israel’s very existence. It has taken almost every opportunity to appease Tehran since it came to office, and has been extremely slow to respond to massive human rights violations by the Iranian regime, including the beating, rape and murder of pro-democracy protesters

Indeed. Because when I want to establish good relations with a country, I push for a global effort to cripple its economy, call it a "military dictatorship" and attempt to isolate it politically.

While Japan's Prime Minister is reeling from a bruising battle with the U.S., Sheila Smith argues that South Korea's President is ascendant:

The skilled President Lee Myung-bak seems to have catapulted his country into a top spot on the U.S. favorite partner list. Despite the deeply difficult domestic politics that confront the South Korean President regarding the undone KORUS trade agreement, he has positioned himself well on virtually every issue that President Obama cares about. Last fall, when Afghanistan’s stability was the top item on Obama’s agenda, President Lee promised to send a South Korean PRT there to contribute. When Obama visited Asia, Lee poured on the personal charm coupled with some very strategic thinking in his intimate conversation with Obama on the problem-solving opportunities ahead.

(AP Photo)

Washington, DC readers should be sure to check out an event this Wednesday at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace on political reconciliation in Afghanistan. Gilles Dorronsoro, a visiting scholar at the Endowment who just returned from the country, will be discussing his trip and the likelihood of a unity government in Kabul.

Interested readers may register to attend Wednesday's event here.

The latest RCP average puts David Cameron's Conservative Party up 4.5 points, giving the Tory leader a week-long window to create some breathing room between the surging Nick Clegg and himself.

Be sure to check the RCP Average daily, and get more opinion and analysis on the British elections from our United Kingdom homepage.

UPDATE: Nate Silver has a thoughtful and thorough analysis on possible parliamentary seat allocations.

Two out of three Japanese voters disapprove of Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama and nearly 60 percent think he should resign if he fails to resolve a feud over a U.S. airbase by an end of May deadline, a media poll showed on Monday....The Nikkei newspaper poll, conducted over the weekend, showed 68 percent of voters disapprove of Hatoyama, up 11 percentage points from the previous poll last month, partly on frustrations over the Futenma U.S. base row.

On Sunday, 90,000 people turned up at a rally against the U.S. base.

(AP Photo)

Nicholas Sarkozy is expected to introduce a bill on Monday that would ban the wearing of full veils in public. A new poll shows the French support some restrictions on the Burqa in public:

Two-thirds of French people want a law limiting the use of face-covering Islamic veils such as the niqab and the burqa, with only a minority backing the government's plan for a complete ban, a poll showed Saturday....The TNS Sofres/Logica poll, which was carried out on Thursday and Friday, showed that 33 percent of French people want a complete ban, while a further 31 percent want a more narrow law applying only to certain public spaces.

The results of the survey of 950 people were roughly the same for men and women. Support for some kind of legal restriction on the full veil cut across age groups, professions and political affiliation, though it was stronger among right-wing voters -- more than 80 percent of them favored a law.

(AP Photo)

Max Bergmann thinks UK candidate Nick Clegg is right to urge the cancellation of the Trident nuclear program. I'm not well versed in the particulars of the Trident debate, but on the broader issue of whether Britain should retain a viable nuclear deterrent, I don't find Bergmann's argument all that persuasive. He writes:

The notion that the UK needs nuclear weapons because of the dangers of Iran demonstrates an outdated world view that sees Britain as isolated and sees security issues in a vacuum. The fact is that the UK is in NATO – which means under Article 5 an attack on one NATO member is an attack on all. This means that an attack on the UK is an attack on the US and therefore the US nuclear deterrent is effectively a UK nuclear deterrent as well. If the UK’s nukes just magically disappeared there would be no practical change in its ability to deter a nuclear attack.The debate over the Trident is therefore at its heart is not about questions of security but about nuclear weapons as a sign of global prestige and clout. The fact is that the role of nuclear weapons has significantly declined following the end of the Cold War, since, as Colin Powell noted, nuclear weapons are militarily “useless.” Clegg is therefore right when he states in defense of eliminating the Trident that “the world is changing, when we’re facing new threats.”

But a Britain that is willing to spend more than $100 billion dollars on a nuclear weapons program that has little real military utility, is not just swimming against the global tide, but is sending an incredibly regressive signal to the world over the importance of these weapons.

So the British should rely on America's nuclear deterrent when the U.S. is supposedly on its own quest to abolish nuclear weapons and limit the role they play in its own deterrent posture. But if NATO is to have a credible nuclear deterrent someone has to have nuclear weapons. If the U.S. under the Obama administration is intent on scaling back and eventually eliminating its own arsenal, it seems a prudent hedge on Britain's part to retain theirs (in what form and how much they should spend on it is a debate for another day)

Britain enjoys collective security today. And while it's reasonable to conclude that they will continue to do so far into the future, predictions are hard, especially about the future. A country ultimately needs to rely on itself for its own security and in this regard, nuclear weapons are not just fashionable, they are vital. And irrespective of any signaling, the truth is nuclear weapons are important. Why else would we be working so hard to make sure no one else can have them?

(AP Photo)

I have to say, I find the effort to rebrand George W. Bush as Woodrow Wilson II rather amusing. Here's Bari Weiss writing in the Wall Street Journal:

Mr. Bush is almost certainly aware that the freedom agenda, the centerpiece of his presidency, has become indelibly linked to the war in Iraq and to regime change by force. Too bad. The peaceful promotion of human rights and democracy—in part by supporting the individuals risking their lives for liberty—are consonant with America's most basic values. Standing up for them should not be a partisan issue.Yet for now Mr. Bush is simply not the right poster boy: He can't successfully rebrand and depoliticize the freedom agenda. So perhaps he hopes that by sitting back he can let Americans who remain wary of publicly embracing this cause become comfortable with it again. For the sake of the courageous democrats in countries like Iran, Cuba, North Korea, Venezuela, Colombia, China and Russia, let's hope so.

For the sake of argument, let's grant Weiss' argument that promoting freedom was the "centerpiece" of President Bush's foreign policy agenda. How'd he do? Well, according to Freedom House, global freedom decreased in each of the last three years of his tenure, continuing through the first year of Obama's tenure.

I happen to think it's foolish to assign blame or credit for the ebb and flow of global freedom to the actions of a single politician or a single cohort of bureaucrats in Washington. But that's the terrain that Weiss has chosen to fight on, and by that measure, the freedom agenda was not successful (at least according to Freedom House's rankings).

Rod Liddle shows you how it's done:

The elevation of Clegg, you would hope, marks the apogee of the cretinisation of the British electorate, in which the public debate is now pitched at a slightly lower level than that implied in the sorts of questions I used to be asked by my two sons: ‘Dad, what would win in a fight between a tiger and a shark? What would win in a fight between a table and a desk?’ It cannot surely drop lower than this, can it? Clegg’s sole pitch, the only thing which scored him points — ‘at least I’m not them’ — was, nonetheless both accurate and had force. It would have had no less force if it had been issued by a gently cooling bowl of oxtail soup on a plinth, either, and would undoubtedly have contained more substance.

Once again, the Obama administration is trampling over the wishes of its allies in an effort to appease America's enemies:

Fresh from signing a strategic nuclear arms agreement with Russia, the United States is parrying a push by several NATO allies to withdraw its aging stockpile of tactical nuclear weapons from Europe.Speaking Thursday at a meeting of NATO foreign ministers here, Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton said the Obama administration was not opposed to cuts in these battlefield weapons, mostly bombs and short-range missiles locked in underground vaults on air bases in five NATO countries.

But Mrs. Clinton ruled out removing these weapons unless Russia agreed to cuts in its arsenal, which is at least 10 times the size of the American one. And she also appeared to make reductions in the American stockpile contingent on Russia’s being more transparent about its weapons and willing to move them away from the borders of NATO countries.

Watching the second UK debate yesterday, I was struck by how narrow the focus on foreign policy really was. China was only mentioned twice and as an aside to the climate change debate. Russia, once, in passing. Iraq, three times, and again as an aside. No mention of India, Asia, Israel, Palestine or the Middle East. (Incidentally, the BBC has an amazing tool where you can search the debate for key phrases.)

I think we have a very unfortunate tendency in the U.S. to expect political leaders to "solve" global problems. But watching the British debate there was very little sense, outside of the climate change and terrorism discussions, that events and geopolitical trends beyond their borders had any urgent meaning.

(AP Photo)

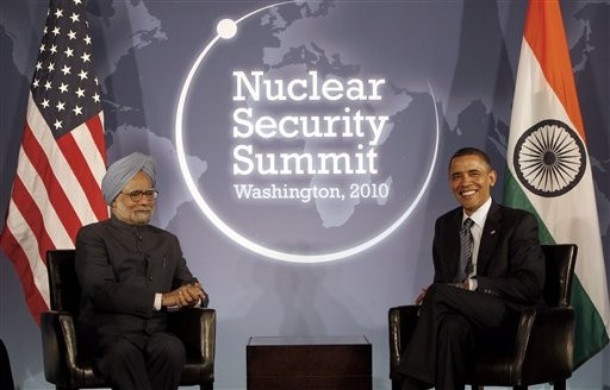

Howard L. Berman (D-CA), chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, issued the following statement yesterday on Iranian sanctions:

“Iran’s intentions are clear, and now is the time to implement crippling sanctions on this reckless regime.“Iran’s claim that it is pursuing only civilian nuclear production falls flat under the weight of deceptions, unexplained activities, and credible documentation. The International Atomic Energy Agency just recently expressed its grave concerns over Iran’s activities noting ‘the possible existence in Iran of past or current undisclosed activities related to the development of a nuclear payload for a missile.’

“During President Obama’s Nuclear Security Summit the international community demonstrated it would not tolerate nuclear weapons in the hands of irresponsible actors. We are moving forward to ensure that legislation enabling tough sanctions is on President Obama’s desk for his signature.”

Meanwhile, Berman is moving forward with Iran sanctions reconciliation.

Alex Massie, who gives Gordon Brown the win in yesterday's debate, dissects Nick Clegg's performance:

As for Clegg, he was solid but not spectacular. There were moments of hesitancy and some rambling but in general I found his manner appealing: he gave the impression of listening to the questions and then thinking about his answers and did more to engage the audience - both in Bristol and at home - than either of the other candidates. He was brave on immigration too and his final line - for those still watching - was excellent: “Don’t let anyone tell you it can’t be different. It can.”

This, minus the rambling, is why I give Clegg the win in debate #2. He seemed to speak more directly to the various audiences, and he got his change and choice message across rather well - getting your message across trumps 'winning' and 'losing' in the traditional debate sense. Televised political debates aren't normal debates.

I thought he got caught up in an eye rolling moment, a la Al Gore in 2000, while pressing Cameron and Brown on immigration, but I think he also had the luxury of getting a little cattier, more direct in this debate, as viewership - like here in the United States - dropped significantly from the first one.

Did you miss yesterday's debate? Well you can watch the opening statements here until we get the full debate video up, and also be sure to check the RCP average every day for the latest poll numbers on the British race.

UPDATE: And this is an awesome debate recap tool.

(AP Photo)

Earlier in the week I wondered if Obama was truly out-of-step with public sentiment in his approach to Israel. I was skeptical, but now CNN reports on a poll that directly addresses the question:

Only a third of Americans approve of the way President Obama's handling the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians, according to a new national poll.A Quinnipiac University survey released Thursday morning indicates that 35 percent of the public gives the president a thumbs up on how he's dealing with the situation between Israel and the Palestinians, with 44 percent saying they disapprove, and just over one in five unsure.

This stands in contrast with how Americans feel about Obama's overall handling of foreign policy, with 48 percent approving and 42 percent saying they disapprove.

Ezzedine Choukri Fishere argues for full nuclear disclosure in the Middle East:

First, it would lay to rest the complaints about double standards in the nonproliferation community and relieve the US - and Israel - from the untenable claim that Israel's nuclear arsenal should somehow be treated as exceptional (a claim that nobody outside Washington and Tel Aviv gives serious consideration). The double-standard argument has been the most successful weapon against nonproliferation, especially in mobilizing public support for nuclear projects like those of Saddam's Iraq, Ghaddafi's Libya or Iran (and you will hear a lot about it in the coming weeks leading up to the NPT review). Second, such a dialogue would significantly decrease the pressure on Arab governments to start their own nuclear programs and abort what could be the beginning of a nuclear race in the region. Third, this dialogue would pave the way for the establishment of a Middle East security regime, which could be the vehicle for addressing a wide range of security hazards in this troubled and troubling region. Finally, such a dialogue might offer a framework for addressing Iran's problematic nuclear activities, especially if accompanied by a package of stabilizing confidence-building measures.

The problem here isn't the substance, but the messenger. As Colum Lynch recently pointed out, Washington's sudden insistence that the world disarm and turn back the nuclear doomsday clock rings rather hollow to weaker nations mulling the nuclear weapons route. Once again - much like with the global emissions debate - the United States, having already developed, proliferated and polluted, is telling the rest of the world what's best. There are obviously finer points and nuances to this perception but, generally speaking, it comes across as more unilateral lecturing from the West.

This of course complicates Obama's rapprochement strategy with Iran. Nonproliferation is important, perhaps too important to rest entirely on the unpredictable - and often erratic - actions of the Iranian regime. And thus far, the case against Iran has been an internationalist and legalistic one; filled with violated protocols, perfunctory deadlines and deliberative hectoring. The president intended to engage - instead he audits.

And I get the idea: Halt Iran's nuclear intransigence, buy time on the so-called doomsday clock and create the necessary breathing room to discuss the litany of other issues in need of resolving. But Obama has instead given the Iranians an opening to make this a global 'north' vs. 'south' argument, which hurts your case when you need countries like Brazil, China and Russia to support an engage/sanction Iran strategy. Rather than providing breathing room, the nuclear debate has instead sucked all the oxygen out of the room.

It's a strategy, to be fair, that I supported - and continue to, albeit tentatively. And perhaps there's still a chance for a fuel swap deal, but I remain skeptical.

(AP Photo)

A new poll conducted by Public Agenda has found the American public less anxious about foreign policy than it's been in four years:

The Foreign Policy Anxiety Indicator stands at 122, a 10-point drop since 2008 and the lowest level since Public Agenda introduced this measure in 2006. The Confidence in Foreign Policy Index, produced by Public Agenda in collaboration with Foreign Affairs, uses a set of tracking questions to measure Americans' comfort level with the nation's foreign policy, much the same way the Consumer Confidence Index measures the public's satisfaction with the economy.The Anxiety Indicator is measured on a 200-point scale, with 100 serving as a neutral midpoint, neither anxious nor confident. A score of 50 or below would indicate a period of complacency. Above the "redline" of 150 would be anxiety shading into real fear and a withdrawal of public confidence in U.S. policy.

Digging into the numbers, the survey found a partisan divide with Republicans evincing more anxiety about our foreign policy than either Democrats or Independents. Despite the overall mood of relative calm, Public Agenda found that most Americans still see the world as a dangerous place. "The number who say the world is becoming 'more dangerous for the United States and the American people' is virtually the same was it was two years ago: 72 percent, compared with 73 percent in 2008," the survey noted.

Despite America's improved image internationally, 50 percent of those surveyed by Public Agenda said U.S. relations with the rest of the world were on the "wrong track." Only 39 percent said they were on the right track.

Americans were also polled on Afghanistan. Forty eight percent said that our safety from terrorism did not depend on our success there vs. 40 percent who believed it did.

Today, Britain's three leading contenders for Prime Minister will square off for their second televised debate. This time, the focus will be on foreign policy. As a primer, you can view the relevant portions of their manifestos here (for Cameron) here (for Brown) and here (for Clegg).

The debate is expected to center on immigration, Britain's nuclear deterrent and the war in Afghanistan. To set the stage, The Independent has a new poll out assessing the war effort:

The vast majority of voters are hostile to the war in Afghanistan and believe the political parties are failing to give voice to their opposition, a new poll has discovered ahead of the televised leaders' debate on foreign affairs tomorrow.The ComRes survey for The Independent and ITV News finds that nearly three-quarters of electors view the conflict as "unwinnable" and more than half say they do not understand why British troops are still in Afghanistan....

High levels of voter dissatisfaction with Britain's eight-year military involvement in Afghanistan were uncovered by the survey. According to ComRes, 72 per cent believe the war, which has so far cost more than 280 British lives, is "unwinnable", with just 19 per cent taking the opposite view.

More than half (53 per cent) say they "don't really understand why Britain is still in Afghanistan", with 42 per cent disagreeing. A gap between the sexes emerged, with 60 per cent of women but 47 per cent of men saying they did not understand Britain's presence in Afghanistan. A sense that the issue has so far been avoided in the election campaign emerged, with 70 per cent saying they believed the main parties did not offer them "any real choice of policies" on Afghanistan.

This U.S. public, by contrast, is more supportive of the war, although lacks confidence in the administration waging it.

(AP Photo)

The Lowy Institute's Michael Wesley pours some cold water on the idea:

Today's US and China are not the same as America and the Soviet Union during the Cold War. The US and the USSR were superpowers, a word that's used so much these days that many have forgotten its original meaning: a power so much larger than all other types of state that collectively they would be no match for it. With this sort of power lead, any sudden change in relations between Washington and Moscow – for better or worse – had a decisive effect on world politics.America and China do not possess that kind of power gap with other classes of states. Unlike just after the Second World War, today the rest of the world is much richer and much better armed.

Furthermore, the Cold War was driven by ideology as much as by power. Today, America and China do not represent powerful, universalist ideologies that speak to the development and doctrinal issues that confront many of the world's societies. Neither state can meaningfully be said to have ideological followers that see the other state and the doctrine it represents as an existential threat to their way of life.

I'd say that many politicians and analysts in America would vigorously contest that last point. America, they would argue, does represent a universalist ideology. Indeed, many of the strongest proponents of that notion believe we cannot live securely in a world populated with political systems that do not share our views and thus have a positive obligation to go forth and spread the revolution. Granted, this idea does not seem to have many takers in the current administration - but administrations change.

We also can't predict how China will ultimately behave as (if?) it continues to close the power gap with the United States.

(AP Photo)

Google has just released a new tool that reveals which governments have requested that Google remove content from its search engine or videos from YouTube. Topping the list: Brazil followed by Germany, India, the U.S. and South Korea. Unfortunately, the number of requests issued by China is considered a "state secret" and was not made public.

Add this to the "Iran can be contained" files.

Alexander Stille unpacks the phenomena:

Berlusconi has transformed the political life of a major nation into a kind of reality TV show in which he is star, producer, and network owner: he is the ultimate “Survivor,” who will lie and cheat to kick others off the island as well as “The Bachelor,” distributing roses to a group of beautiful young women. Consider that Berlusconi’s approval ratings are consistently higher than Barack Obama’s. As The Daily Beast pointed out recently, Obama’s TV ratings and poll numbers have gone down in lockstep as his health care legislation has been weakened and unemployment has remained high: “The fact is he had 49.5 million listeners to [his] first speech on the economy. On Medicare, he had 24 million. He’s lost his audience…. He has plunged in the polls.” Berlusconi, facing public scandals similar to those of Tiger Woods and John Edwards, has kept his audience.Berlusconi has understood that contemporary politics is a permanent campaign. In the old days, a US president campaigned for six months and governed for three and a half years. Obama rather quaintly followed this old-fashioned model, working largely behind the scenes to promote health care and other legislation, while the Republicans held the stage, claiming that the Democratic plan imposed “death panels” and socialized medicine. Berlusconi would never have let that happen.

(AP Photo)

Angus Reid has a new poll out measuring American sentiment toward the war in Afghanistan:

This month, 51 per cent of respondents (down three points since February) say they support the military operation involving American soldiers in Afghanistan, while 39 per cent are opposed (up one point).Two-in-five Americans (43%) believe the country did the right thing in sending military forces to Afghanistan, while three-in-ten (31%) think it made a mistake.

Overall, 52 per cent of respondents say they have a clear idea of what the war in Afghanistan is about.

When The War is Over

When asked about what they think will be the most likely outcome of the war in Afghanistan, the findings show little fluctuation since February. One-in-four Americans (25%,) expect a clear victory by U.S. and allied forces over the Taliban, and 26 per cent foresee a negotiated settlement from a position of U.S. and allied strength that gives the Taliban a small role in the Afghan government.

Significantly fewer respondents foresee either a negotiated settlement from a position of U.S. and allied weakness that gives the Taliban a significant role in the Afghan government (9%) or a military defeat of U.S. and allied forces by the Taliban (4%).

As for whether people have confidence in the administration, Angus Reid found greater skepticism:

Only 33 per cent of respondents (-2) are very or moderately confident that the Obama Administration will be able “finish the job” in Afghanistan, while a majority (53%, +1) are not too confident or not confident at all.

Daniel Larison further analyzes Michael Auslin's contention that any reduction in American defense spending will cause a cascade of failures across the international system:

Auslin had warned that Chinese military build-up, Russian influence in post-Soviet space and an Iranian bomb would lead to a situation in which “global trade flows will be stressed, the free flow of capital will be constrained, and foreign governments will expand their regulatory and confiscatory powers against their domestic economies in order to fund their own military expansions.”One of the reasons I didn’t originally address these concerns is that I don’t find these to be the likely consequences of China’s continued rise, Russian resurgence in its own neighborhood and Iranian membership in the nuclear club. Why will global trade flows be stressed? China is heavily dependent on its export trade to sustain economic growth at home. It has no incentive to disrupt or “stress” trade flows or to embark on policies abroad that would lead to this. At present we see increasing economic integration of Taiwan with the mainland, and the Hatoyama government has held out the possibility, however remote it is at the moment, of forming an East Asian economic community modeled on the European Union. China is investing in (and exploiting) markets all over the world in states where Western companies typically do not go or where they are not allowed to go. So why will the free flow of capital be constrained if China continues to increase its military power? Are we not instead seeing increased trade carried out by and among the BRIC nations? Aren’t emerging-market countries, including China, engaging in noticeable economic innovation?

In this vein it's worth reading Anthony Bubalo & Malcolm Cook's piece in the American Interest (sub required), documenting the rise in investment between China, Russia, and India and all across Asia and the Middle East. The reason Asia is growing in economic might is because of a growing trading network. They're participating in the global economy in ways that benefit them and trying to close it off to the U.S. or create an autarkic regional bloc doesn't appear to be the goal. And if it was, one way to breach it would be to get more trade deals through Congress and move to patch things up with India.

I realize I'm really late to the party on this Gates Iran memo story but, to be honest, I find it mostly overblown and par for the course of internal administration dialogue (Richard Haass, keep in mind, pieced together thoughtful memos of dissent back in 2002 and 2003, yet still supported the eventual invasion of Iraq).

Marc Ambinder, drawing a parallel to the 2005 NSA disclosures, writes:

Whoever leaked this memo to the Times has to bear the responsibility of knowing that they could very well have fortified Iran's intention to resist international pressure, that it could very well have complicated the careful cultivation of China and Russia on sanctions, that it could steel Israel's spine in ways that would be perhaps deleterious for the region.

My reaction: Eh. I think this is a classic case of beltway over-thinking. Think about it from the Iranian regime's perspective: you're covered on two fronts by tens of thousands of U.S. (and other Western) forces; Washington is arming and rearming your regional foes; it's rather obvious that either Israel, or the United States or BOTH are engaging in some sort of covert sabotage campaign against your nuclear ambitions, and one of your nuclear officials just defected to the West - a defection obviously facilitated by your enemy, the Saudis.

One memo doesn't change these realities for the Iranian regime, it simply affects the minds and already entrenched opinions of those in Washington.

Aaron David Miller's must-read essay on why he's abandoned one of Washington's most cherished orthodoxies - the peace process - has set off a debate about the future of America's most favorite past time.

The fact that the U.S. has labored so long at something without succeeding is either a testament to its valiant persistence or foolish obduracy (or both). Either way, the current attempts to revive Israeli-Palestinian peace talks seems hopeless, which leads to an obvious question: what does a "post peace process" American diplomacy looks like? For Israel, at least in the short term, it looks quite good. They continue to receive American support without enduring American demands. For the Palestinians, the short term looks bad. Whatever hopes they had of prying further concessions from Israel will vanish.

Over the medium-to-long term the prospects for both parties will shift. Israel will face the demographic challenge of a blossoming Palestinian population living under its control. Demands for a "one state solution" will grow and the democratic and Jewish character of the state of Israel will be under strain. So too will the prospects for a negotiated settlement.

Consider the views of the Palestinians in 2010:

Residents of the West Bank and Gaza Strip are opposed to the creation of a Palestinian state within the 1967 borders with some land exchange as part of a final solution to the current impasse with Israel, according to a poll by An-Najah National University. 66.7 per cent of respondents reject this notion.In addition, 77.4 per cent of respondents reject making Jerusalem the capital for both an eventual Palestinian state and Israel.

It strains credulity to believe that this outlook is going to be reversed as the demographic balance between Israelis and Palestinians shifts.

(AP Photo)

In some sense Obama's new policy, rather than the wishes of the Democratic Congress, reflects the new Democratic majority, even as it is at odds with the country at large (63 percent of the American people express support for Israel). More to the point, no alliance can long withstand such a marked divide, in which Republicans are overwhelmingly pro-Israel and Democrats quite clearly are not -- that divide leads to something like the radical change of heart from Bush in 2008 to Obama in 2009. - Victor Davis Hanson

Hanson is right to suggest that we're seeing some fairly sharp partisan divergence over Israel. But I think he's wrong to suggest that President Obama is somehow broadly out of step with the American people when it comes to his policy toward Israel.

As proof of his claim, Hanson relies on the Gallup poll sited above, but nowhere does that poll imply that somehow President Obama is anti-Israel. And there have been others polls which suggest that public opinion on the Israel-Palestinian issue is less clear cut: an Economist/YouGov poll in March showed a more nuanced picture of American sympathies in the Mideast conflict. A Zogby poll showed a majority thought the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was harmful to U.S. interests and 50 percent of respondents said the U.S. should steer a "middle course" between the two parties. Earlier in March, Rasmussen found that 49 percent of Americans thought Israel should be required to stop settlement building as part of a peace deal.

Now put this in the context of what President Obama has actually done: publicly and repeatedly affirmed America's "unbreakable" commitment to Israel's security, exerted considerable efforts trying to derail Iran's nuclear program, relaunched the peace process, ratcheted up public criticism of settlement building and denied Prime Minister Netanyahu a White House photo-op. A fair-minded observer could disagree with some of these decisions and argue that the Obama administration has behaved boorishly and counter-productively toward an ally by criticizing it in public. But I don't think we can conclude - as Hanson does - that these policies reflect an administration in the grip of "campus multiculturalists" or that they're otherwise way out of step with the American public.

Bill Kristol didn't like what he heard from the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff yesterday when he said that military strikes and a nuclear-armed would be "equally destabilizing." Writes Kristol:

But Mullen's formulation of geostrategic equivalance ignores a massive difference between the two outcomes: Even assuming the degree and kind of "destabilization" would be the same in both the cases of attack and appeasement (which I don't think would be so), one scenario--attack--leaves Iran without nuclear weapons, at least for now; the other--appeasement--means Iran would have nuclear weapons going forward. Which unstable outcome is less damaging to U.S. interests? I think the answer is pretty clear: An attacked Iran that does not have nukes.

One problem with the formulation above is Kristol's seeming belief that any U.S. military strike on Iran does not escalate. Bombing a few Iranian nuclear sites - even if it provokes some blowback against U.S. troops in Iraq and Afghanistan - is a more palatable option than having to wage a broader war against the country, but no one can guarantee that one step does not lead to another. Imagine, for a moment, that a few days after the U.S. airforce reduces Natanz to rubble, a few American airliners are blown up at the hands of Hezbollah terrorists. The U.S. would have to respond. As Reuel Marc Gerecht argued in Kristol's own magazine, it would be unwise to think that a "limited" military operation against Iran wouldn't blossom into something much larger - in part because we couldn't be sure we did enough damage to Iran's nuclear capability without some kind of ground presence and because Iranian reprisals could force our hand.

America would win any military confrontation with Iran, but as we've seen in both Iraq and Afghanistan, that's almost besides the point. Military victories are transitory without some kind of durable post-war settlement - and Washington's track record in this regard doesn't inspire one with a lot of confidence. So I think we can read Mullen's "geo-strategic equivalence" as a plaintive cry against having a third Humpty Dumpty in the Middle East that the U.S. military is somehow supposed to patch together again.

Democracy in America pours some more cold water on the idea that other countries are "free riding" on American military power.

Noah Shachtmann passes along Admiral Mullen's thoughts on a military attack on Iran's nuclear facilities:

“Iran getting a nuclear weapon would be incredibly destabilizing. Attacking them would also create the same kind of outcome,” Mullen said. “In an area that’s so unstable right now, we just don’t need more of that.”