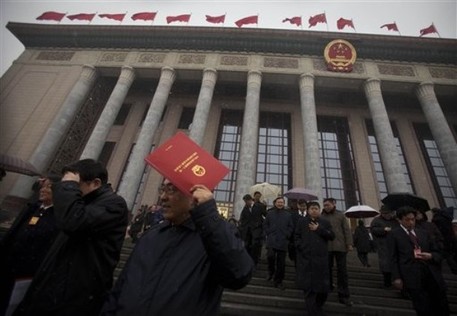

Today, the Associated Press reported on the wrap-up of China's National People's Congress. A largely rubber-stamp legislative body of 3,000 delegates, this year's Congress passed the Communist Party government's annual report with 97.5 percent approval.

Although not a central part of the story, the article goes on to state the following:

"Delegates, who include hundreds of army officers, themselves are carefully vetted by Communist Party officials and selected in a perfunctory election by lower-level committees." [Emphasis added]

It's true that most of these delegates are predetermined in the high-level politics of China, yet the abundance of reporting out of the West on the "perfunctory" processes in Chinese politics understandably skews the perception of its audiences. As much as those in America or elsewhere buy into the common narrative that China is a near-totalitarian regime, it has been experimenting seriously with inner-party democratic reform in lower level elections for over 14 years.

According to one report (PDF) by Joseph Fewsmith in the China Leadership Monitor , in 2001-02, about 5,000 of 16,000 official positions were chosen through elections, some more democratic than others. In some places, there have even been direct, competitive elections for a position, called a â??public recommendation, direct electionâ? (å?¬æ?¨ç?´é??).

And aside from the institutionalized democratic processes, like elections, there are all types of democratic negotiating in China via social movements -- a field which I research. For example, workers might protest over nonpayment in China's southern sunbelt region and, wanting not to risk larger instability, local governments appease their demands. Democracy is more than punching a ballot.

Is China a one-party state? Yes. Is it more repressive than most states in the West? Yes.

But these facts are beside the point. Westerners, and particularly Western media and newswires, have to start seeing some of the complexity in the gigantic world of Chinese politics. As much as it confuses our worldview, we might have to decide that China is not Big Brother.

Kevin Slaten was a junior fellow in the China Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Now, he lives in Taiwan on a Fulbright Grant. His opinions in no way reflect the views of the State Department or Foundation for Scholarly Exchange. He blogs at http://www.kevinslaten.blogspot.com/.

(AP Photo)