New York Times columnist Paul Krugman published on Sunday his monthly column about China's dastardly currency policies. The column repeats many of Krugman's earlier comments about global "imbalances" and market "distortions," as well as his not-so-subtle demand that the U.S. Treasury Department label China a currency manipulator in its semi-annual report on the subject (not coincidentally due next month). Now, I've already expressed some serious doubts about Krugman's thoughts and intentions on the China currency issue, so I won't get into that again because, unlike PK, I can't get away with recycling my work. Instead, I want to focus on Krugman's new and bellicose policy recommendation for solving the China currency "problem":

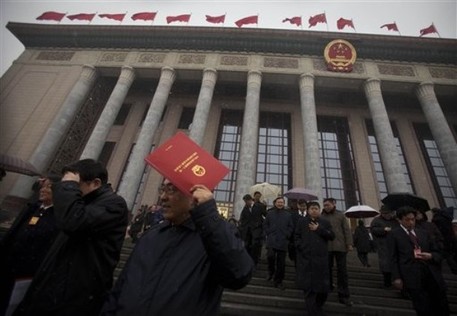

Some still argue that we must reason gently with China, not confront it. But we’ve been reasoning with China for years, as its surplus ballooned, and gotten nowhere: on Sunday Wen Jiabao, the Chinese prime minister, declared — absurdly — that his nation’s currency is not undervalued. (The Peterson Institute for International Economics estimates that the renminbi is undervalued by between 20 and 40 percent.) And Mr. Wen accused other nations of doing what China actually does, seeking to weaken their currencies “just for the purposes of increasing their own exports.”

But if sweet reason won’t work, what’s the alternative? In 1971 the United States dealt with a similar but much less severe problem of foreign undervaluation by imposing a temporary 10 percent surcharge on imports, which was removed a few months later after Germany, Japan and other nations raised the dollar value of their currencies. At this point, it’s hard to see China changing its policies unless faced with the threat of similar action — except that this time the surcharge would have to be much larger, say 25 percent.

I don’t propose this turn to policy hardball lightly. But Chinese currency policy is adding materially to the world’s economic problems at a time when those problems are already very severe. It’s time to take a stand.

Yes, you read that right. Former free trade guru and Nobel laureate in trade economics Paul Krugman just strongly advocated the unilateral imposition of 25% tariffs on all Chinese imports if China doesn't respond to U.S. demands to appreciate its currency by 20%-40%. Even I am shocked by this suggestion. Not only does it mean that Krugman, who also recently advocated

carbon tariffs as a way to force developing countries to impose development-killing climate change policies, finally needs to tear up his free trader card, but it also represents one of the more short-sighted and absurd lines of reasoning that he's ever produced.

Indeed, by my count, Krugman's arguments for this 25% tariff fail from a historical, practical and economic perspective.

(1) Krugman completely distorts (or, to be kind, misreads) history. As Dan Drezner points out, that U.S.-Germany episode didn't quite unfold as Krugman claims:

It's certainly true that the dollar was overvalued back in 1971. What Krugman forgets to mention -- and see if this sounds familiar -- is that the Johnson and Nixon administrations contributed to this problem via a guns-and-butter fiscal policy. They pursued the Vietnam War, approved massive increases in social spending, and refused to raise taxes to pay for it. This macroeconomic policy created inflationary expectations and a "dollar glut." Foreign exchange markets to expect the dollar to depreciate over time. Other countries intervened to maintain the dollar's value -- not because they wanted to, but because they were complying with the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates. Nixon only went off the dollar after the British Treasury came to the U.S. and wanted to convert all their dollar holdings into gold.

In other words, the United States was the rogue economic actor in 1971 -- not Japan or Germany.

So the U.S. in 1971 wasn't the U.S. of today - it was China. Minor detail! So much for that historical and theoretical justification for angry unilateralism, huh?

(2) Krugman is oblivious to geopolitical reality. Why on earth does Krugman think that the Chinese response to a 25% U.S. tariff will be a change in its currency policy? If the last several years have proven anything re: China policy, it's that China will not be bullied into changing its domestic policies. Indeed, when provoked or antagonized, the Chinese are pretty childish - almost always reacting with self-spiting stubbornness and/or direct retaliation (see, e.g., the Section 421 case on Chinese tires or the recent Google censorship case). AEI's Phil Levy discusses this obvious reality here, and Krugman even mentions China's often-irrational recalcitrance in his new column when he discusses Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao's angry response to recent accusations by U.S. politicians (and op-ed columnists) about China's alleged currency manipulation.

So does Krugman really think that a 25% tariff will lead Wen to pipe down, fall in line and quickly appreciate the RMB? If so, Krugman just hasn't been paying much attention. Far more likely, China will attack U.S. exports with equivalent unilateralist verve, and hello trade war! (And I don't mean one of those fake "trade wars" that bad economics journalists have recently grown fond of writing about. I'm talkin' about a knock-down-drag-out trade war.)

(3) Krugman's solution - and I can't believe I'm typing this - is economically illiterate. Krugman speaks of U.S. unilateral tariffs only in terms of their affect on China's exporters, and he speaks of Chinese retaliation to this U.S. unilateralism only in terms of China dumping its U.S. debt (something that he, correctly, doesn't think they really can do). Yet nowhere does Krugman discuss the awful economic effects that a 25% tariff on all Chinese imports would have on the U.S. economy, which, as Krugman himself admits, remains "deeply depressed." As anyone with even a rudimentary understanding of international economics knows, such tariffs would just devastate American families and businesses because, among other things, (a) the United States imported almost $300 billion in Chinese goods last year, (b) almost 60% of all imports (not just Chinese) are capital goods and equipment used by U.S. companies in order to remain globally-competitive, and (c) trade with China has been proven to dramatically benefit lower-income American families. In short, this ain't the 1970s anymore (thank goodness).

Indeed, we have a great modern day test case for Krugman's awesome unilateral trade prescription in the recent 35% tariffs that the Obama administration imposed on Chinese tires under Section 421 of U.S. trade law. The results of those nasty tariffs were skyrocketing domestic tire prices (even with significant trade diversion) and severe supply shortages, with tire retailers and poor American consumers hardest hit. And Krugman wants to repeat and amplify these protectionist harms by applying similar tariffs to all $300 billion in Chinese imports? Unbelievable.

Now, coming from someone not versed in trade and economics, ignoring these "unseen" harms would just be stupid. But for Paul Krugman - someone who obviously knows better - to not at least mention the obvious pain that his recommendations would impose on American businesses and families is the height of intellectual dishonesty.