(Continued from Part 1 & 2)

By Patrick Chovanec

The Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) may seem like an odd name for one of the most militarized places on the face of the earth. Just 30 miles north of Seoul, and 80 miles south of Pyongyang, it was the armistice line at the end of the Korean War: its winding contours stretching across the peninsula, 155 miles from east to west, mark the positions held by the opposing armies when that conflict ground to a halt in 1953. Officially the war never ended. Both sides merely observe a long and occasionally precarious cease-fire. Today the DMZ — which effectively serves as the highly fortified boundary between North and South Korea — is one of the last Cold War frontiers in existence, a place of watchtowers, land mines, and soldiers staring each other down across barbed wire fences. And this morning our group was heading there — from the “enemy side” of the border.

I climbed aboard the bus at our hotel and headed towards the back, where our minders sat, handing them each a packet of cigarettes. I don’t smoke myself, and for all I know neither do they, but Marlboros are valuable currency in North Korea, just as they were when I visited the Soviet Union back in the 1980s. Sitting next to our minders, and establishing a friendly rapport with them, made it easier to ask their permission to snap photos along our route. And while being under their constant surveillance may sound intimidating, they actually turned out to be quite pleasant and friendly in return.

One of the minders for another group, of Europeans, got a big kick out of learning new American slang. He jokingly warned his group that if they stepped out of line, he would “open a can of whoop-ass on them.” When his group ran late and we accidently ate the lunch he had scheduled for them, I taught him the expression ”you snooze, you lose” – quite handy for a tour guide. He loved it. I’m sure none of these guys would have hesitated to lower the boom if we caused any trouble, but we knew the rules and were careful not to give offense. Maybe there was a little bit of Stockholm Syndrome at work, but our interactions with our minders ended up being one of the highlights of our trip.

Our group had two minders, who I will call Mr. Nervous and Mr. Smooth. I’d like to introduce them, because I’ll be referring to them — with appropriate discretion — in upcoming posts. Both of them were young guys, in their late 20’s. Mr. Nervous had decent English, but had difficulty following some of our conversations. Because he wasn’t always certain exactly what was being said, he tended to become anxious that maybe we might be up to no good. He was kindly, though, and a little bashful, except when he got up in front of the bus and serenaded us with Korean folk songs like a star contestant on North Korean Idol. Mr. Smooth, unlike his companion, didn’t sweat the small stuff. His English was more fluent, which made it easier for him to relax and engage us in more meaningful conversation. He was thoughtful and eager to know our impressions of his country. He struck me as the kind of person who, if things were to ever change, would go very far.

Our route took us south along the “Reunification Highway,” giving us our first real glimpse of the countryside. People often ask me whether we ever saw evidence of starvation in North Korea. I tell them no, but then the main, high-profile corridors we travelled outside of Pyongyang were the last place you’d expect to see such a thing, if it did exist. But even from the highway, it was clear that life in the DPRK was hard. It was harvest time, but tractors were exceptionally rare, and even beasts of burden — scraggly ponies and bony oxen — were few and far between. Most people toiled in the fields by hand, and carried immense bundles of sticks or wheat on their backs, piled three or four times their own height. Even when they set these burdens aside, they ambled along permanently bent over by the weight. I had never seen farm work quite so grueling, even in the poorest parts of rural China.

The “highway” soon narrowed to a single well-paved lane in either direction. We saw no other vehicles, except for a convoy of three or four buses that passed us midway, going in the opposite direction. They carried South Koreans who had crossed the DMZ first thing that morning, presumably heading for family reunions or reunification-themed tours in Pyongyang.

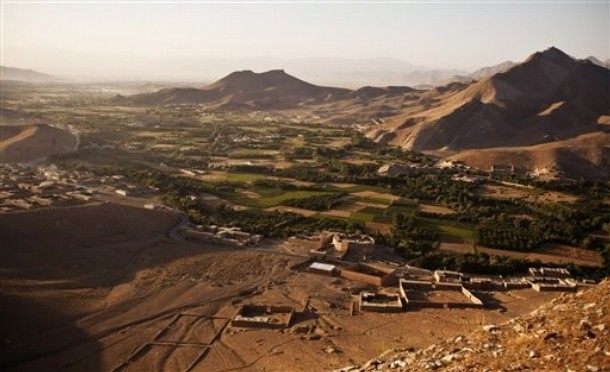

I had visited the DMZ once, several years before, from the South Korean side. Apparently there had been official negotiations taking place, which prevented us for seeing the Joint Security Area (JSA) at Panmunjom. Instead, we were taken to a mountain-top observation post where we could look across the valley into North Korea through coin-operated telescopes. Even at such a distance, the tension was palpable. About a mile away, you could see a huge flagpole, over 500 feet tall, flying a massive North Korean flag. At the far side of the valley, white box apartment buildings marked the city of Kaesong, with a tiny but clearly visible statue of Kim Il-Sung standing atop an outlying hill. It felt completely inaccessible, like looking at the moon.

Next they took us to one of four tunnels the North Koreans had secretly dug under the DMZ. There may be others, yet undiscovered. This one was found in 1978 on a tip from a North Korean defector, and is wide enough for one whole division to pass through it per hour, in the event of an invasion. Climbing down its slope through solid rock, for over 350 meters at an angle of over 10%, holding onto a rope, made it feel strangely like a ride at Disney World. Then you reach the bottom to find the first of three giant steel and concrete plugs marking the border. Standing deep underground, realizing you are a few feet away from North Korea and wondering what there might be on the other side of those plugs, is enough to raise the hair on the back of your head.

This time, arriving from the north, we wouldn’t be climbing down any tunnels, but we would get to visit the JSA at Panmunjom and see the actual border up close. When we finally arrived at the entrance to the DMZ, the bus stopped and let us out in a small parking lot in front of a massive concrete gate. Tall, olive-clad soldiers stood guard with automatic rifles, while others stood around smoking. We entered a building with a large map and relief table, and an officer briefed us (in Korean) on the layout of the DMZ. Outside the briefing hall there was a souvenir stand selling bottles of amber-colored wine with large cobras floating coiled up inside.

One by one, the empty buses pulled through the concrete gate. Then we were directed to line up, platoon-style again, and walk silently in single file through the gate to re-board the buses. On the other side, we found them lined up along a narrow sunken road, with stone walls on either side topped with huge concrete blocks. These blocks were rigged with cables to fall and block the path entirely in the event of an attack.

The DMZ is a surprisingly peaceful place, at least as you drive through it. In the years since the war, the absence of human habitation has turned some stretches into something of a wildlife preserve. Nearby towered the immense flagpole with the North Korean flag, which I had viewed through the telescopes from the other side. Farther away, just peeking over the trees, we could see a similar flagpole with a South Korean flag atop it. I felt like an astronaut on the moon gazing back at the earth. Our first visit, to the compound of buildings where the armistice had been signed in 1953, was historically interesting but uneventful. We were all eagerly anticipating our first real glimpse of Panmunjom, and the border itself.

Someone had remarked, earlier that day, that the then U.S. envoy to North Korea, Christopher Hill, was supposed to be entering the country that day to attend negotiations in Pyongyang. We didn’t give it much thought until we arrived at Panmunjom and marched up to the large reception building on the North Korean side of the JSA compound. As we approached the main entrance, a small group of Westerners in business suits emerged and begin climbing into awaiting vans. It was Christopher Hill and his entourage! If he saw us at all, he probably assumed we were Russians or something. We were just 20 feet away or so, and we wanted to shout out “Hey, we’re Americans!” But the North Korean side of the DMZ isn’t a smart place to suddenly shout anything, much less that particular piece of information. So we watched quietly and excitedly as he was driven away. We tried to explain to our minders exactly who that was, but they were non-plussed. But for us, it was precisely what we had come to see: history in the making.

From the viewing platform atop the reception hall, we could get a sense of the overall layout of the JSA. Directly opposite was a futuristic-looking building, the South Korean counterpart to the one we were now standing atop. Between them lay a series of long corrugated metal huts, parallel to each other and painted bright blue. These were the rooms where U.S., South Korean, and North Korean army officers met regularly to discuss practical issues related to maintaining the ceasefire. If one side or the other has a problem or demand, they make an announcement over a loudspeaker and the teams meet together in the blue huts. In the gap between each hut, a thin concrete line, about a foot across, marks the final boundary separating each side’s territory.

Back outside the reception building, we were lined up once more and marched down to the blue huts. There was no tension, just a mood of quiet intensity. Everyone knew that Panmunjom had seen vicious outbreaks of violence over the years, sudden gunshots or mass brawls involving axes and bayonets, but most days it was quiet, like this. The North Korean guards watched us nervously, intently. From this side, at least, the South Korean MPs actually looked much more intimidating in their shiny bullet-shaped helmets and what-we-have-here-is-a-failure-to-communicate sunglasses. Across from us, lined up at the base of the South Korean reception building, was a Western tour group — Americans probably – who no doubt were wondering who we might be.

We entered one of the blue huts and took seats around the tables inside. Those of us on the far side of the room were informed, by a North Korean officer, that we were now standing on South Korean territory. Any relief we might have felt, or any thoughts of making a quick bolt for friendly lines, was negated by the presence of a North Korean sentry standing firmly astride the far doorway.

After we filed back out to the North Korean side, we began taking pictures of each other standing in front of the dividing line. In the urge to take a memorable photo, our gaggle of visitors began pushing ever closer to the sensitive gap between the blue huts. Suddenly a North Korean guard clapped his hands and the relatively calm mood changed completely. We had pushed the limit, the guards had become agitated, and it was time to leave. We hurried away before trouble could brew.

We boarded our buses and returned along the same road to exit the DMZ. Our next stop was an old Confucian temple on the outskirts of Kaesong, which served as a small museum devoted to ancient Korean culture. It was beautifully restored, and at one point I hung back from the group a bit to take a photo without so many people in it. The compound was completely enclosed, and I couldn’t have been more than 20 yards away, in clear view, but Mr. Nervous had seen enough excitement for one day and quickly shooed me along. “Stay with the group!” he half ordered, half beseeched.

When I caught up to the group, inside one of the side courtyard buildings, everyone was gathered around a display of ancient artifacts. The guide was pointing out a comb, a needle, and finally a spoon. “Koreans invented the spoon,” she murmured proudly. What? We didn’t quite catch that. You said Koreans invented the spoon? “Yes,” she said, “Koreans invented the spoon.” The group was a little dumbfounded, but wanted to be polite. So, ahh, when was that? Slight hesitation before she responded: “Two thousand years ago.” Okay . . .

Now I happen to know that the ancient Egyptians had spoons, and plenty of them, 5,000 years ago. In fact, spoons probably date from a lot earlier than that, most likely the Stone Age when some clever fellow cut a gourd in half to form a ladle. But before we left Beijing, one of our Western tour coordinators gave us a piece of advice. “These people don’t have a lot,” he explained. “You have plenty. Sometimes people are going to say things that may seem silly to you, but just remember that while you get to go home, this is all they have. Let them have it. What does it cost you? Just let them have something.”

All of us stood around for a moment gawking at each other, recalling the same words of advice. And then we smiled, and gave in. “Wow. Koreans invented the spoon. How about that? Good for you guys.”

We broke for lunch in Kaesong, eager to try out our new knowledge of spoons. The city, barely a few miles from the DMZ, is home to a big industrial park where South Korean companies have been allowed to set up cross-border factories. The wages of the North Korean workers are paid to the DPRK government, which keeps most of it and passes along a tiny fraction to the employee. We weren’t allowed to visit any factories, but we did stop for lunch just below the statue of Kim Il-Sung atop the hill, the same one I had seen through the telescope several years before. So near and yet so far.

Like walking on the moon.

-----------

Patrick Chovanec is an associate professor at Tsinghua University’s School of Economics and Management in Beijing, China, where he teaches in the school’s International MBA Program. He blogs at http://chovanec.wordpress.com/ where this post first appeared.

Now one of those people, Ahmad Vahidi, has been selected for Defense Minister of Iran: The Guardian has the story,

Now one of those people, Ahmad Vahidi, has been selected for Defense Minister of Iran: The Guardian has the story,